For Josh Berer, a D.C.-based professional calligrapher currently co-leading a calligraphy and bookmaking workshop at the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery, there’s much to see in the museum’s new exhibition, The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

Berer, who specializes in traditional and contemporary Arabic calligraphy, is one of only three full-time Arabic calligraphers in the United States. For Berer, who fashions his own brushes and marbled paper, it’s the subtleties of the craft that initially piqued his interest.

Berer remembers when he was first transfixed by a work of calligraphy. It was 2005, and he was holed up in a library at the University of Washington, poring through a collection of calligraphy books. He happened upon a manuscript on the four Noble Caliphs, with each word interlaced in a single brushstroke.

“That was the first time a piece of calligraphy knocked my socks off,” Berer recalled.

Today, Berer studies under prominent calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya where he’s learning, among other things, how to pick up on subtleties in master works.

“You need little training to distinguish good calligraphy from bad calligraphy,” Berer explained. “But it takes years of refinement to distinguish the good from the great.”

That eye for detail that carries over to Berer’s work, which he enjoys sharing with a community of calligraphers he met traveling in Istanbul. The handful of artists post pictures of their work and historical manuscripts to Instagram and Whatsapp, with most photos garnering upward of a hundred or so likes per post.

If there’s one thing Berer has learned from his fellow calligraphers and years of study, it’s that calligraphy is far from a dead art. In fact, many of his clients request tattoo designs in his calligraphic style.

“Oftentimes, calligraphy is presented as an artifact, but it’s a continuing tradition that’s been passed down for centuries,” he said.

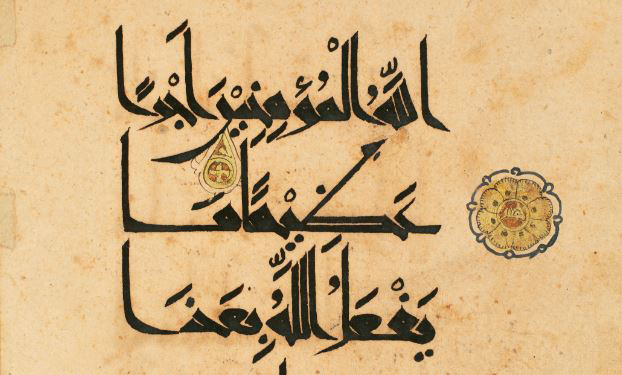

Among his favorite styles of calligraphy is Thuluth, an elegant, cursive script which frequently places among the winning entries in the annual International Calligraphy Competition. In The Art of the Qur’an, Berer gravitates to a two-part Qur’an, one likely from Iran or present-day Afghanistan and dating back to 1050.

“It’s straightforward, simple, and elegant,” Berer said of the vividly illuminated script.

If there’s one thing visitors should take away from the exhibition, Berer said “it’s the versatility of the script and the breadth of style contained within a single genre.”

“This exhibition is unique in its presentation of the evolution of these manuscripts, both geographically and stylistically.”

This piece was written in collaboration with the Smithsonian Arthur M. Sackler Gallery exhibition The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, on view through February 20, 2017. For more information on Josh Berer’s work, visit his website.