It takes me about twenty minutes to walk from my parents’ house to the train station in Donabate, North County Dublin, Ireland. I don’t need to read the street signs to find my way around the once-small village I lived in as a child, but I often take note of one that points toward the graveyard. It reads “Reilig,” and it reminds me of my family members buried there.

I walk by my old secondary school, a relatively modern building that was constructed when I was a student, and I see the impossible-to-miss sign on the front: “Coláiste Pobail Domhnach Beathach”—Donabate Community College. I remember my Irish-language teacher and I smile, thinking that it was probably because of her brave commitment to Irish and its place in this town that the sign got there. There’s a new building beside my old school that was built after I graduated: an Irish-language primary school. I wish I was born late enough to attend. Sometimes those students walk with their teachers in the village, and it brings me endless joy to hear their joy—their joy through Irish.

I get to the station and hear the familiar warning: “Seasaigí taobh thiar den líne bhuí, le bhur dtoil”—please stand back behind the yellow line. I always think about my granddad, Richard, as I wait for my train to the city. Throughout his entire career, he worked for the railway and was a signalman in Donabate station. He and Grandma Dolores always encouraged my connection to the Irish language. Grandma Dolores would tell me about her experience going to an Irish-medium primary school in Dublin city when she was four. I remember how she used to laugh as she explained that she didn’t have a clue what was going on the first time she stepped into the classroom. She can’t tell me that story anymore, but I can pass on her laughter.

I used to go to this train station with her and Granddad Richard on the way to visit her mother, my Nana Lily. My cousins and I once danced in the garden of Nana’s nursing home in Dún Laoghaire. Nana and Grandma sang, “a haon, dó, trí, a haon, dó, trí,” as our little feet tapped away to their beat.

Granddad Richard always calls me when he has watched a show on TG4, the Irish-language television channel, and we often try to remember songs that he knew as a child. It is through him that I am connected to the person who is probably the last in my family to have spoken Irish as a first language, one of his grandmothers. I discovered this by looking at census records from 1901 and 1911, which show that she was an Irish speaker.

By the early twentieth century, the people of Ireland had endured hundreds of years of British colonial rule that brought with it violence and dispossession. Memories of An Gorta Mór, the Great Famine in the 1840s and 1850s that caused the death of about one million people, were still fresh. For many, the Irish language was attached to experiences of poverty, suffering, and violence, and English was imposed as the language of economic success.

Perhaps it was this that led my great-great-grandmother to turn to English when she moved away from her native home in the Conamara region to eastern Ireland, eventually settling in Dublin, the capital. Granddad Richard has told me that he can’t remember her ever speaking Irish there. I think often about what might have led her to make that decision.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Ireland experienced a cultural revival as part of its independence movement. The Irish language was promoted as a marker of identity that separated the Irish people from the English. After part of Ireland gained independence, the new Republic of Ireland established Irish as its first official language.

While it was recognized that Irish was an important part of the entire nation, certain regions were acknowledged as more Irish-speaking than others. These largely rural areas, known as the Gaeltacht regions, are home to a higher proportion of Irish speakers, who some believe use the language more “authentically.” Sometimes people do not consider Irish spoken outside of these areas as equally important. Irish speakers in Dublin, outside of the Gaeltacht, are at times forgotten and erased despite the relatively high number of speakers in absolute terms. Speaking Irish is not seen as the norm in Dublin, and this negatively impacts language use. Perhaps this, too, played a part in my great-great-grandmother leaving her language behind when she left one of these Gaeltacht areas.

Granddad Richard and Grandma Dolores were born into an independent Irish state, and since then, members of my family have been able to learn Irish at school and attend immersion summer camps in a Gaeltacht region. But none of this has overcome the centuries of oppression that came before, the ideas and behaviors around Irish that came from that period, and the association between Irish and only certain areas of the country. In fact, some of my family’s experiences in school added to their disconnect from the language.

Throughout the twentieth century, English remained the dominant language in my family, but Irish hadn’t completely disappeared. It was still in Nana and Grandma’s dance cheers and Granddad’s songs. Certain words were sometimes used in Irish instead of their English counterpart, like geansaí instead of “jumper.” Irish grammar could also be found in the structures used in English, like “he gave out to me” for “he scolded me,” which comes from the Irish term ag tabhairt amach. But it wouldn’t be until the twenty-first century that a member of our family would embrace Irish as theirs again and push for their life in Dublin to be a life in Irish.

I was born in 1996 and consider myself lucky to have been raised with more freedom than many Irish people had during the last few hundred years. I had good experiences learning Irish in school, and the language was one of my favorite subjects from a young age. My parents responded positively.

My mum remembers some Irish that she learned in school, but she felt distant from it for a long time. My dad is English and only recognizes a few words in Irish after thirty years of living in Ireland. One of his great-grandfathers moved from Ireland to England in the nineteenth century, and was possibly an Irish speaker, but we don’t know much about him. My parents have regrets about not learning and speaking more Irish, but they were discouraged when they were younger and have since had other priorities. Their relationship to Irish has become more positive due to my involvement with it, which pushes me to continue. We have supported each other mutually in that way.

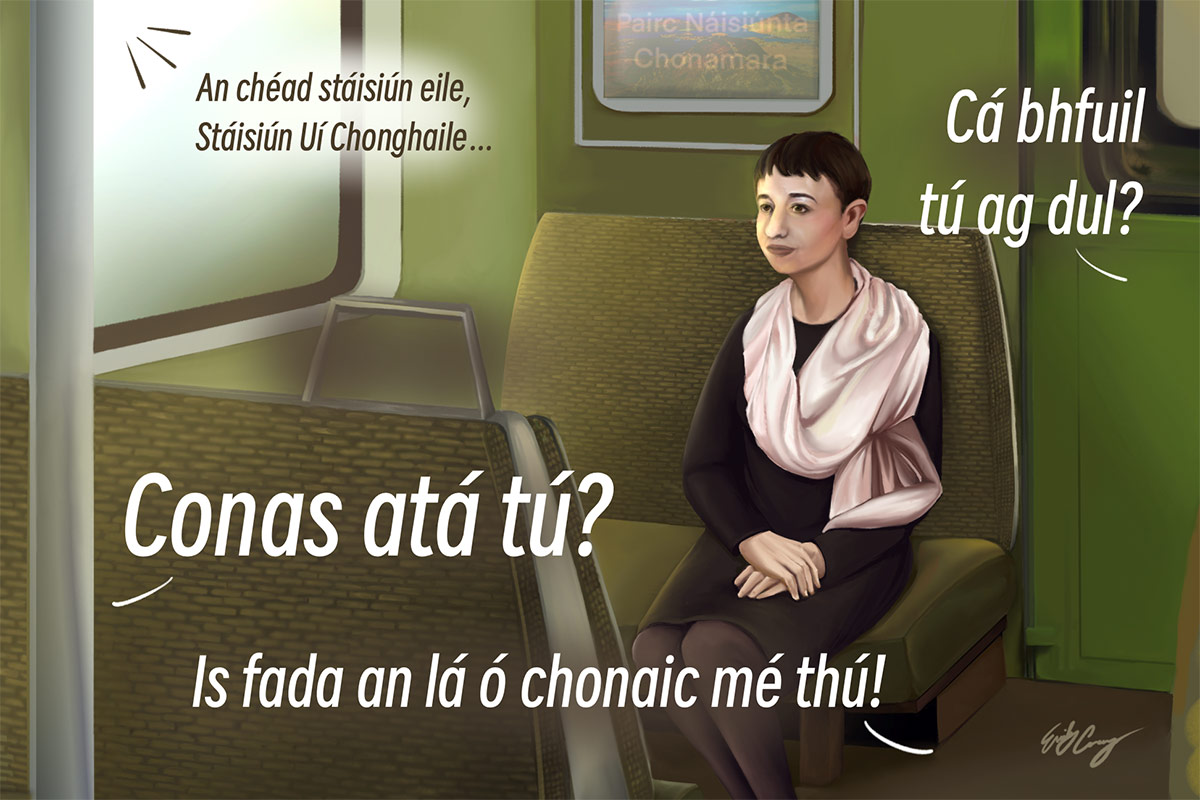

From when I was eleven, my parents encouraged me to attend Irish-language summer camps, first in Dublin and later in the Conamara Gaeltacht. I returned to the area that my great-great-grandmother was from and was fully immersed in the language for the first time. During the summer, I would go to classes, play sports, and make friends in Irish. I was able to attach so many happy memories and experience key moments of adolescence through the language. This helped to battle the shame that had been attached to it for generations. Still, returning to my hometown after summer camp meant returning to a life mainly in English. I found it hard to imagine Irish connecting to my life in Dublin. As I’ve gotten older, though, I’ve learned to see that it definitely can. My train journeys to the city remind me of this.

I put on my headphones and listen to a podcast or take out a book while I’m on the train. It’s impossible to concentrate on either of these tasks when I hear Irish floating above the seats. It calls out to me. It finds me. I try to catch a glimpse between the seats of who might be speaking—perhaps I know them, or perhaps I don’t. Either way, it catches my attention and makes me happy. I hear teenagers in school uniforms deboard, saying goodbye to their friends. “Slán,” they say, in the most natural way imaginable. Saying goodbye to my school friends like that didn’t seem natural to me when I was in their position only a decade ago. This change, too, makes me happy.

Donabate is about twenty kilometers (twelve miles) from Dublin City, and the train between them takes about half an hour. Although Donabate is a small town that is physically separated from the city, an urban Dublin identity extends beyond the city and suburbs to the entire county. Many people in the town have family from the city, and you often hear inner-city accents in the English spoken there.

Once I get to the city, I’m pulled along in the stream of people heading to work, to museums, to shops, to parks, to no specific destination at all. My destination looks different every time, but it is most often related to the Irish language.

Sometimes I go to a conversation circle, an event where people come together in cafés, parks, or universities to practice and speak Irish together. I’m often nervous when I’m going to a circle for the first time, though this fades quickly once I’m there. Each circle looks different in terms of size, location, and ages and backgrounds of the speakers. But I am always greeted with a warm welcome by all. Groups who may have been coming together weekly at the same time and place for years, if not decades, make me feel like a valued member. I am quickly chatting away about my life and asking them about theirs. I am touched by the interest, curiosity, and support that these people—strangers as of an hour ago—show toward me. I take in their views on what is happening in the world and share some of my own. We learn together.

Sometimes, I go to the Pop Up Gaeltacht, an event where speakers come together in a different Dublin pub each month and make Irish heard. I go knowing that it is a movement that began in this very city in 2016 and has since inspired similar events all over the world. I go knowing that it has put Dublin on the Irish-speaking map that it has so often been excluded from. I go knowing that it has inspired so much of my own thinking about the place of Irish in our city.

When I arrive at the pub, the linguistic takeover is sometimes so successful that Irish spills out onto the street. I push my way in. I find old friends and meet new ones. We have a laugh, we solve the world’s problems, and we get noticed. One time, an event was overrun by students attending a Christmas disco; trying to communicate in Irish with people I had met only minutes before while hordes of students screamed “Dancing Queen” beside us had me laughing hysterically. We soon escaped to a neighboring pub and some interested students followed.

Sometimes I go to see a play, a film, a comedy gig, or a concert. I take my seat and look around for familiar faces. I watch a Greek tragedy translated and performed in Irish at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. My dad does, too, thanks to subtitles in English that hover above the stage. I sit in a cinema on O’Connell Street, close to where Grandma Dolores grew up, and watch a film about a group of women in Kerry racing in a naomhóg-rowing competition. I cry, not only because of the film’s moving story and the women’s sharp wit, but for knowing that I am the first in a long line of women in my family to go to the cinema and enjoy a film in Irish. I find a corner to sit among friends in Club Chonradh na Gaeilge, Dublin’s Irish-language pub, and we laugh as we listen to jokes that would smash any image of Irish being the language of the Catholic establishment to pieces. I go to a Kneecap concert and join thousands of people in the Olympia Theatre as we rap verses in Irish at the top of our lungs. All of these events and more like them inspire me endlessly, as I take in speakers’ talent, creativity, and commitment to art in our language.

Sometimes I move my body to the rhythm of the language. With a lot more control than I had as a child Irish dancing in Nana’s nursing home, I stretch and hold and breathe to the sound of the yoga teacher’s instructions and my classmates’ breaths. I feel great after yoga in general, but I feel especially great after yoga in Irish. If the aim is to replenish my mind and spirit, then doing it in Irish makes the most sense. I move to the language at the 1916-themed rave in Club Chonradh na Gaeilge, too. Dancing wildly and screaming in Irish is, while perhaps unorthodox, an interesting way to commemorate a rebellion that aimed to liberate Ireland from British colonial rule. I dance, I laugh, and I think about how lucky I am that I can freely do this in my language.

Sometimes I go to An Siopa Leabhar, an Irish-language bookshop where I buy books for the next generation born into my family. I look through the children’s section and pick out the most colorful picture books. I take a quick look around for myself, grab a book or two more, and head to the till. The children’s books are for my cousins’ children. One tells me about the new Irish words he has learned every time he sees me, his face lighting up as he does. He also enjoys challenging me by giving me words to translate. I am amazed at how quickly he learns to say them and humbled by some of the more difficult ones.

Another, who is only eight months old, laughs hysterically when I speak Irish to her. Throwing her little head back, Zoey revels in the sounds of “Tá tú ar fheabhas ar fad”—you are absolutely amazing. Her favorite song is a song in Irish called “Óró mo Bháidín.” Zoey’s mum, my cousin, is learning Irish on Duolingo. If our family’s history in the twentieth century was one lived in English, I have hope that the twenty-first century will be different. I like to think that the colorful books and stories that I bring back from Dublin help with that.

Sometimes I go to catch up with college friends over a meal. After eating, we walk along the River Liffey (An Life), the river that divides Dublin in two, and take a seat to continue our chats and watch the water. People approach us, having heard us speaking Irish together. “It’s so great to hear Irish!” they say. They ask us where we are from and are quite shocked when I say I’m from Dublin. As we catch up on life, laugh at old stories from university, and people-watch, our casual conversations become something more. They show passersby that something they thought didn’t exist in fact does—that the picture of Dublin that they’ve had in their minds isn’t the full picture, that the linguistic expectations placed on people from and in Dublin don’t need to define us.

Sometimes I walk around the city alone. I try not to walk quickly with my head down and my headphones on. I walk instead with my eyes and ears open to the world. I see the bilingual street signs and try to learn the true street names that I was only ever taught in English. I see stickers in Irish stuck to lamp posts: stickers with a vocabulary lesson in Irish and stickers welcoming immigrants to Dublin that appear the day after a racism-fueled riot takes over part of the city. I hear languages from all over the world. I see moments of connection where strangers meet and share a smile, where old friends run into each other, where a dog lifts their head to meet a human hand. I see tents and sleeping bags everywhere. I see immense poverty.

At the end of a day spent in this beautiful and tragic city, I head for the last train home. There are no trains back to Donabate after midnight, so I am often running from an event with other Irish speakers who live in towns on the same train line. We dash through streets full of people out partying. I wonder what they must think as we run by, shouting to each other in Irish about how many minutes we have left before the train leaves. We make it on the train, take our seats, and catch our breath before continuing conversation. We bring the language with us from the city to our towns. I get off at Donabate station and get a lift home. I tell my parents about the day I’ve had and the people I’ve met before saying goodnight to them and the dog and going to bed.

It takes me a while to get to sleep as I am still caught up in the exciting conversations and music and laughter. I feel lucky and privileged that I get to live like this. I think about how my life wasn’t always this way: there were many points in my teenage years when I felt lost and lonely and confused, when I didn’t really understand my place in the world. I don’t feel like that very often anymore. Speaking Irish in Dublin brings me community and brings meaning and purpose to my life. It helps me to imagine that another world is possible: a world where people can speak their language freely, where urban speakers are recognized and supported, and where community is central to how we live our lives. I give thanks to all the Irish speakers who have fought for this world and continue to do so.

Before I close my eyes, my thoughts return to the century that my family has lived in Dublin, a century spent largely detached from our language. It ends with me.

Alexandra Philbin is a language revitalization mentor with the Endangered Languages Project and a PhD candidate at the University of València, where she focuses on the use of minoritized languages in urban areas. Her work has taken her many places, but her background as an Irish speaker from Dublin stays with her wherever she goes.

About the Endangered Languages Project

The Endangered Languages Project is a collaborative online space to share knowledge and stories, explore free learning resources, and build relationships to support Indigenous and endangered language communities around the world. Get in touch at feedback@endangeredlanguages.com.