We all speak, and language—the languages of our homes and families, our daily conversations with friends, the stories we tell about who we are and where we come from—connects us to each other and to our communities and cultures. In this way, language is fundamental to our identities.

But what happens to the relationship between your language and identity when you move from one country to another? When you no longer speak the same language as your parents or grandparents? When the languages you speak don’t “match” how you self-identify or are perceived by others?

We live our lives through language, and it is often assumed to be a direct index of who we are. But identity is more complicated than that, and so is language. While language is an important part of culture, who speaks what language and to whom naturally changes when people migrate and adapt to new circumstances.

For one thing, there’s usually immense pressure (often officially enacted through language policy and schools) to “shift” to the majority language. Immigrants can internalize this language discrimination and/or maintain a strong sense of pride. And, of course, immigrants’ children and grandchildren develop unique identities which integrate new languages and cultural practices with the desire to maintain or relearn their family heritages. Their words, which follow, illustrate the importance of language in their lives and communities.

Language and Heritage

“Listening to someone tell me about how they were never able to communicate with their grandmother opened up the idea of the social boundaries which occur solely from a choice of whether or not to teach their child their native tongue.”

—Festival intern, Hungarian immigrant parentage

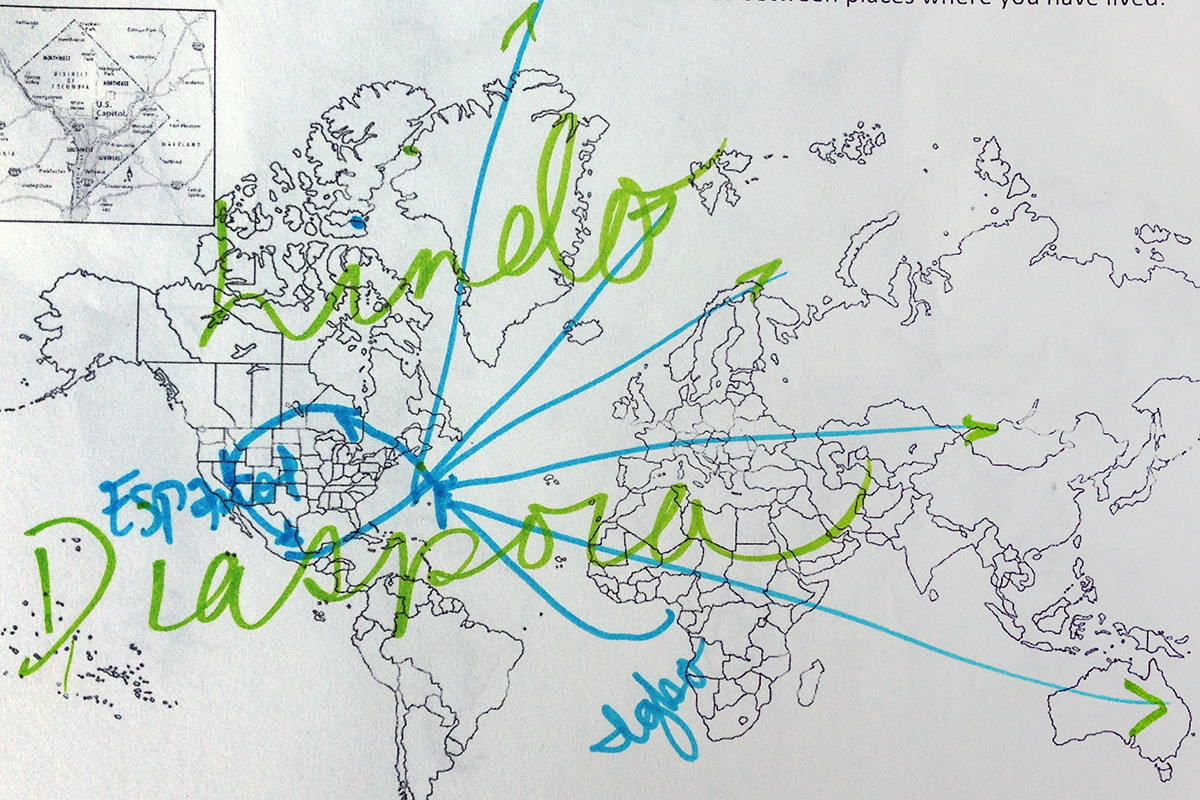

At the 2017 Smithsonian Folklife Festival’s On the Move program, visitors of many backgrounds reflected on language in their own lives and family histories through an open mic conversation and a drawing activity to map personal migration stories. They spoke an incredibly wide range of languages—at least thirty-five plus five dialects of American English—all connected in different ways to their lives and experiences. In these conversations, they revealed language’s important role in connecting family and heritage and learning new cultures.

“I was raised in Iran, so I speak Farsi,” one woman began. “I also speak English because I was raised bilingual. I also speak French because Iran was very Francophile. Now I’m studying Spanish once a week, because I find it to be a beautiful and useful language. [Being multilingual] opened a lot of doors. People are more hospitable when you visit their country and attempt their language.”

From her daughter’s perspective, speaking Farsi is a central factor in sustaining a relationship with her extended family and learning their experiences and values.

“I speak Farsi, and I’m learning French right now,” she said. “I like to talk to my grandparents. Everyone in my family speaks Farsi so when you go and visit them they’re like, ‘I’m so happy you speak Farsi!’ They tell me all these stories in Farsi and I kind of know what their life is like in Iran.”

Changing Language

“Language is more than a means of communication. Language is a symbol of cultural heritage that endures through change, but that also evolves to adapt to change.”

—Festival intern, West Africa/Washington, D.C.

Historically, the American experience has been characterized by the loss of indigenous and immigrant languages under pressure to assimilate and “be American.” When enslaved people were brought to this country, they too lost heritage languages. One visitor spoke with sadness about language loss in her family.

“The languages that were lost in my family, which were Italian, Dutch, and Polish, weren’t passed on, we learned English. My parents were taught English, so that’s what they taught me,” she said. Showing her drawing from the map activity, she explained, “I drew coming and going because I haven’t returned to the places where my family is from, but [I have traveled] to different regions through the connection of languages.”

While regretting the loss of her family’s heritage languages as a consequence of mainstream assimilation pressure, she also celebrated the opportunities that come with learning new languages, commenting that learning Spanish at school let her appreciate cultures she otherwise would not have known.

Sharing Language

“Sharing a language opens many doors, and it allows you to connect on another level, because you’re making the effort to get to know their culture.”

—Festival visitor

Mobility can change habits and raise awareness of diversity even within “the same” language, community, or country. A young Peruvian immigrant reflected on how her awareness of language and identity has changed through immigration. Before coming to the United States and learning English, she never thought about her Spanish, assuming everyone spoke the same way. Now her perception of Spanish has changed.

As she made friends from different Spanish-speaking countries, she noticed different vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, becoming aware of diversity even within her first language. She also noticed that the way she speaks Spanish changes in different situations, using certain slang and intonations only with fellow Peruvians.

In a separate conversation, hip-hop artist Christylez Bacon identified migration’s influence on language while singling out slang in Washington, D.C., as part of local identity and a means of personal connection.

“The vernacular’s very important,” he said. “Sometimes with vernacular, it could be like someone knows that we have a similar life experience. If I say something to you like, ‘What’s cracking with you?’ you know that, ‘Oh, this person speaks my language. We here.’ [But with someone else,] ‘Oh, hello, my friend, how are you today?’

“My grandma’s from Memphis, Tennessee, and all the generation from my mom, all them born, raised Washingtonians. So, you know, we all speaking English, but we speak different versions of it. The syntax might be different, different vocabulary, different little words. It’s really nice. When I think about how my folks from the South speak English and how we speak English as D.C. people from the hoods… they’re English words, but we just totally flipped them. They mean something totally different.”

Bacon celebrates diversity and innovation within English and the fact that migration leads to language change, while honoring language’s strong associations with “home.”

The child of Chinese immigrants, Stan Lou was raised in Greenville, Mississippi, and now works with the 1882 Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the Chinese and Asian American experience that co-produced a series of presentations for the On the Move program. He described to me his upbringing in the Mississippi Delta and how the region’s substantial Chinese American community navigated their position in the 1930s and 1940s under Jim Crow laws. He remembered feeling “burdened” by language and culture, wishing to just be American and lose his Chinese language and identity. He felt pressure to assimilate, while Chinese elders accused the second generation of losing their language and culture, calling them “hollow bamboos.”

After years of trying to erase his cultural identity, Lou traveled to China to teach. Despite difficulty speaking Chinese—and his students’ difficulty understanding his Southern drawl—he reconnected with his ethnic identity. Having come to terms with his identity as Chinese American, he now mentors Asian Pacific American youth. While problems of discrimination and “perpetual otherness” persist, he finds that there has been progress. They encounter less racism and fewer limitations that he did in his youth, and they are better equipped to move in multiple worlds. Instead of the intense language shame he experienced, younger generations are better able to maintain their languages and use them for translation, identity, and participation in the world.

Tuning into the Conversation

-

Language map activity for Festival visitorsPhoto by Amelia Tseng

-

Language map activity for Festival visitorsPhoto by Amelia Tseng

-

Language map activity for Festival visitorsPhoto by Amelia Tseng

The rich, often unrecognized diversity in the brief examples above is nothing new. Diversity is a fact of human life and experience; however, prevailing cultural narratives too often define “who belongs” in what group often erase experiences which challenge labels. As we move away from static notions of identity to dynamic, intersectional understandings, space opens up for new voices and conversations.

In national debates about immigration, it is easy to lose sight of our common history of diversity and mobility. At the Festival, it was great to hear ordinary people, with different lengths of history in the United States, share the importance of language and see their stories honored on the National Mall. But the conversation is bigger than any single event or language history.

Looking around, there’s a new conversation going on around language and identity. It’s an important part of the fabric of daily life. The conversation is about the change that happens when people move to new places, adopt new customs, and meet, fall in love with, and marry people of different backgrounds.

What happens when you don’t speak “your” language? Does it challenge your authenticity? Who has the right to judge? Does our focus on social categories divert recognition of new forms of identity?

This conversation on reinventing language and identity carries on in many channels: the audience-storytellers at the Festival, productions like Alien Citizen, the Latino Rebels blog, NPR’s Code Switch, and more. We need to tune into the conversation. As our lived experience of diversity expands, so our understanding of language needs to acknowledge and celebrate the dynamic diversity that is and has always been at the heart of the human experience.

Amelia Tseng is a research associate at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and an assistant teaching professor at Georgetown University. She holds a PhD in sociolinguistics from Georgetown University.