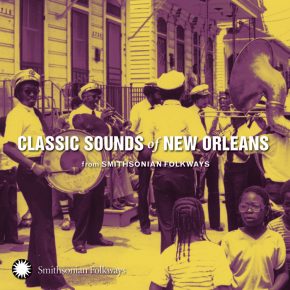

The musical traditions of New Orleans are among the most joyous, passionate, and influential sounds to be found in America. Whether classic jazz, gospel, rhythm and blues, or brass band street music, the distinctive sounds of the Crescent City have flowed continuously and freely from the soul of a community with a unique history and way of life. Several factors contributed to New Orleans’s unusual development: its founding in 1718 as an outpost of French colonization; its relatively isolated location along the Mississippi River near the Gulf of Mexico; its close proximity to the Caribbean and Latin America; and its unusual blend of cultures.

Over the years, hardships resulting from a brutally hot and humid climate, several plagues, and countless hurricanes, floods, and other disasters led to a special appreciation for life. Numerous holidays and feast days of the predominantly Catholic city also contributed to an attitude among many New Orleanians that attaches greater importance to celebration and pleasure seeking—through food, drink, music, dancing, gambling, and good times, often to excess—than to “less serious” issues such as punctuality, business, and progress.

By the nineteenth century, New Orleans was full of musical activity, with everything from opera and classical music to military marching bands, dance music, religious songs, and ethnic folk music. The diverse African American population of New Orleans introduced, maintained, and transformed a number of musical styles throughout its history. Among the city’s large free black population were the mixed-blood Creoles of Color, who were often well versed in European classical styles. Some received training in Europe and returned to promote classical music as performers, teachers, composers, or devotees.

Hear “Sounds from New Orleans,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

Along with other southern areas with large black populations, New Orleans was home to African American folk music as it developed from slaves and their descendants in the form of work songs, street cries, spirituals, and dance music. A longstanding tradition of West African-derived drumming, chanting, and dancing, as performed by enslaved and later free blacks in Congo Square and other locations, left a rich legacy of exciting rhythms and public celebration that has flavored nearly all local music to this day.

The late 1800s saw a wave of anti-black legislation, racial violence, and social unrest. One result in New Orleans was a cultural merger between blacks and the now disenfranchised Creoles, considered under this new legislation to be black. African and European-derived musical traditions further influenced each other, as various kinds of teaching and exchange continued among the previously separate black groups. In line with the celebratory spirit of New Orleans, the tension, anger, and frustration resulting from the intensified African American quest for freedom and equality led to revolution and protest that took artistic forms in addition to legal ones.

Between 1890 and 1910 new folk traditions arose in New Orleans—most notably, jazz and the Mardi Gras Indians—as popular practices that openly expressed the hopes, aspirations, needs, and emotions of the African American community. Originating and first performed among relatives, friends, neighbors, and extended family members, these customs provided a kind of freedom, democracy, visibility, unity, and individual recognition that was restricted or absent from daily, mainstream black existence. Both the jazz and Mardi Gras Indian traditions expressed a symbolic equality for all, allowing for creative competition, acceptance, pride, and social and spiritual uplift—both collectively and individually.

Mardi Gras Indians

The Mardi Gras Indian tribes are groups of elaborately costumed African Americans, predominantly men, who parade through New Orleans streets on Mardi Gras and St. Joseph’s Days. The intention of these black “Indians” is to pay homage to the American Indian spirit of resistance and recognize the cultural ties between the two communities. The Mardi Gras Indian tribes are actually continuing to transform West African customs that go back to New Orleans’s earliest decades.

Hear “Music of the Mardi Gras Indians,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

Much time, money, and effort—not to mention countless feathers, beads, sequins, and other materials—are used in preparing their boldly colorful costumes that both reflect traditional characters and constitute creative individual statements. Typically, several months of collective work from family and friends are necessary to produce each year’s cherished “new suits.” Dozens of tribes, with evocative names such as the Creole Wild West, Wild Tchoupitoulas, and Wild Magnolias, each have coveted positions such as the big chief, wild man, or spy boy, carrying different responsibilities and degrees of honor and respect.

Year-round activities such as preparing costumes and musical rehearsals, as well as actual parading on customary days, all help to constitute a transformed existence in which pride, strength, respect, and nobility mask sometimes harsh everyday socioeconomic conditions. So serious was the Mardi Gras Indian persona in the past that deadly violent confrontations often resulted from random meetings of rival tribes on carnival day.

Fortunately, modern-day battles are of a friendlier nature, taking the form of competitions for the most skilled dancing and most beautiful costume. As they parade through black neighborhoods joined by hundreds of followers, the Indians sing and chant a variety of songs, both in English and in unknown or secret dialects. They are accompanied by a small band of drums, tambourines, and percussion instruments playing African-style rhythms.

Jazz

While the Mardi Gras Indians remain a local tradition of New Orleans’s African Americans, jazz spread outside of that community in its early years to have a major impact on the international music scene. It was during the socially turbulent decade before 1900 that legendary cornetist Charles “Buddy” Bolden and others began to use collective improvisation and driving rhythms and to emulate on horns the vocal styles of blues and black religious song, thus creating a loose, exciting, and more personal way of playing ragtime, blues, marches, hymns, and popular dance music.

This new style, not called “jazz” until later, replaced refined society orchestras and quickly spread to every class and ethnic group in the New Orleans area. Jazz became a visible and popular accompaniment to every type of event imaginable: both indoors and out, in any neighborhood, at nearly any time of day or night.

The typical early jazz bands of four to seven members were very competitive and represented another way in which individuals and groups could gain recognition, self-worth, and respect. Early jazz focused on group improvisation through defined instrumental roles, but the development of highly personal individual sound and expression became equally important.

As jazz spread across America in the late 1910s and 1920s in the persons of New Orleans legends King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Louis Armstrong, and others, it also maintained its unique character as the voice of black New Orleans.

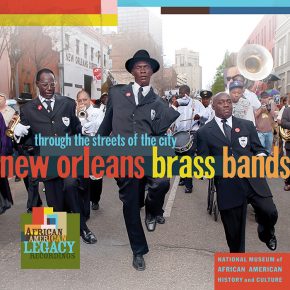

New Orleans jazz’s social significance and local community ties are most obvious in the large parades and funerals sponsored by black “social aid and pleasure clubs” and benevolent societies. The annual parades of these popular mutual assistance organizations may include several divisions of members dressed in elaborately colored outfits complete with decorated hats, fans, sashes, baskets, and umbrellas. They are accompanied by one or more brass bands, which traditionally play an energetic version of New Orleans style jazz. The syncopated rhythms of the tuba and bass drum give these street bands their very distinctive and lively sound.

The procession would not be complete without the “second liners”—the hundreds or even thousands of anonymous people who follow the parade throughout its duration, dancing and cheering all the way. When public streets are filled by such community parades and the crowds of spiritually charged black New Orleanians they attract, defiantly colorful outfits and freeform “second line” dancing combine to provide, if temporarily, a limitless freedom and a forum for symbolically acting out democratic ideals and unity, often elusive in the “real” world.

The “funerals with music,’’ later called jazz funerals, are by tradition honorable processions that give a grand send-off to a deceased person, especially a social club or benevolent society member or a jazz musician. Life and death are juxtaposed as brass bands play both slow, sad dirges (to lament one’s passing) and joyous, up-tempo songs (to recall good times and to celebrate ultimate freedom and a better existence in union with the Creator). During the slow mournful procession with the deceased, club members and onlookers strut in a graceful and respectful manner. After the body is released or symbolically “cut loose” (buried or allowed to go to the cemetery), faster-paced celebratory music is accompanied by joyous “second line” dancing.

Spotlight on Liberty Brass Band. Video by Charlie Weber

Other Musical Styles

All New Orleans musical traditions have been influenced by national trends and styles, which were often reinterpreted or absorbed into local cultural expressions. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, New Orleans became one of several major centers of rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll. Though the city cannot claim to be the birthplace of these new popular music styles, a blending of brass band, blues, gospel, jazz, Caribbean, and Latin American sounds shaped the city’s own unique rhythm and blues sound and style. There were a number of artists, bands, and composers whose influence went far beyond the city. Only in New Orleans could someone like Professor Longhair weave the music of Jelly Roll Morton, boogie-woogie, and rumba into a unique piano and vocal music style.

During the late 1970s and early ’80s New Orleans saw yet another major musical development: the revival and evolution of brass bands. Young groups including the Dirty Dozen and Rebirth Brass Bands established a revolutionary new street sound by blending contemporary popular music and modern jazz with local rhythm and blues, funk, traditional jazz, and Mardi Gras Indian styles.

By 2000 a never-ending crop of new modern brass bands had largely replaced the few remaining traditional groups. The contemporary brass band movement has been highly successful, both in the African American community and in the worldwide commercial arena. Modern brass bands remain a popular part of social club parades and funerals, but are just as likely to bring the New Orleans street sound to festivals, nightclubs, local parties and weddings, recordings, and international tours.

Spotlight on Hot 8 Brass Band. Video by Charlie Weber

The spirit and sound of New Orleans music, in all of its forms, are heard and felt around the globe. Even today’s urban hip-hop has given birth to a local rhythmic version called “bounce.” Several local rappers, among them Master P, Juvenile, Lil’ Wayne, Baby, and Mystical, have been highly successful, at times using their hometown sound and culture for inspiration.

New Orleans has remained among the most important and influential music centers in the world. Its laidback lifestyle, family traditions, close community ties, Creole humor, amazing cuisine, and unique view of life promised to ensure that the communal flame and rhythms that run from Congo Square through jazz, gospel, rhythm and blues, the Mardi Gras Indians, funk, and brass bands would continue to sustain its traditions while giving birth to new and exciting music forever.

The Hurricane

However, the arrival of Hurricane Katrina of August 29, 2005, dealt a devastating blow to New Orleans—one that has threatened the city’s physical, social, cultural, and economic future. In “the worst natural disaster in American history,” 80 percent of the city flooded. More than 1,500 people perished, hundreds were injured, and many others went missing. Many homes, businesses, and buildings were destroyed or severely damaged.

Nearly a year after the storm, several hundred thousand area residents remained outside of the city or state, as many neighborhoods were abandoned and in ruin, with little or no sign of recovery. A scarcity of jobs, housing, schools, medical services, and other basic needs, as well as environmental and health concerns, left over two-thirds of the pre-Katrina population questioning how, when, and if they could ever return home. Many experienced confusion, frustration, and hopelessness as they confronted a number of social, economic, political, and racial issues facing the previously majority African American city.

Photographer Hugh Talman discusses the devastation he encountered in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. He and curator David Shayt (1952–2008) surveyed the aftermath of the storm and rescued several objects on behalf of the National Museum of American History, including a clarinet donated by Michael White. This interview was conducted in 2015. Video by Charlie Weber

The neighborhoods that produced generations of musicians, social clubs, Mardi Gras Indians, and eccentric characters that gave New Orleans its identity were devastated, their populations displaced, dispersed, and focused on basic survival, not celebration. Many realized that the disaster was not yet over, as they struggled with a difficult and confusing process of rebuilding. Though there have been a few jazz funerals and social club parades in recent months, many neighborhood streets that once bounced with the “second lines” are now uncharacteristically quiet and still. In the predominantly Black 7th Ward, the lonely tattered remains of a once majestic Mardi Gras Indian suit are seen nailed to the outside of a house: the lifeless carcass of a once vibrant existence, but one implying a defiant vow to return.

Since the media storm that brought the fate of Gulf Coast victims of Hurricane Katrina into the consciousness of the world, there has been renewed interest in New Orleans culture. Many musicians have been the focus of relief organizations and assistance. Some have been performing steadily around the world. Several musicians have relocated for the long term, citing better conditions and pay in other cities.

The fate of New Orleans’s musical traditions and cultural heritage is in serious jeopardy. Some residents have indeed returned, others are making plans to do so, many others remain undecided, and some have permanently relocated. While some predict the demise of century-old cultural traditions, others believe that tragedy will inspire musical creativity or lead the New Orleans sound farther, influencing other styles wherever displaced musicians reside. Questions remain whether the tourist industry, large conventions, nightclubs, and other musical employment venues will return. Mardi Gras, the French Quarter Festival, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival were well attended: a promising sign.

As the vulnerable city struggles for recovery and identity, only time will tell if, when, and how much of the magic city will return. Now is a good time to reflect upon and savor the unique sound, spirit, and euphoria that New Orleans’s musical traditions have shared with the nation and the world for generations.

Read more in New Orleans issue of Smithsonian Folkways Magazine

Dr. Michael G. White is a relative of first-generation New Orleans jazz musicians, a professor at Xavier University, and an acclaimed jazz clarinetist, composer, bandleader, writer, producer, and historian. Now the leader of the Liberty Brass Band, he produced New Orleans Brass Bands: Through the Streets of the City (Smithsonian Folkways, 2015).