What do the Motown sound and hip-hop music have in common? Each is the musical inspiration for a vital dance tradition that thrives in the African American community of Washington, D.C.

And these two styles of black dance—the smooth partner coordination and intricate turns of “hand dancing” performed to Motown classics, and the rhythmic steps and weight shifts with elaborate, syncopated arm and torso gestures done to the rhythmic polyphony of hip-hop music—what do they have in common? Each serves as a generation’s prime marker of identity and vehicle for artistic expression. Together with a third style, go-go, they provide artistic alternatives to people of different ages and aesthetic sensibilities.

Hand Dancing

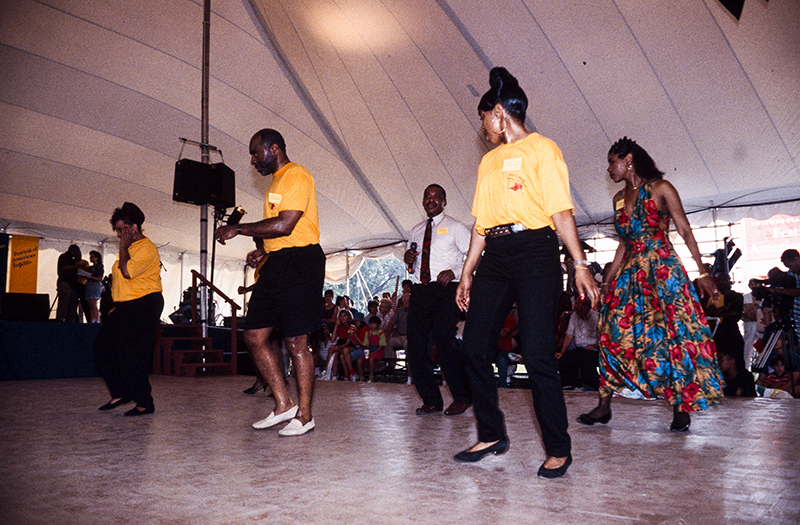

Hand dancing was born and bred in Washington, D.C., during the Motown era, which began in the late 1950s. It is essentially a smooth version of the Lindy Hop that features almost constant hand holding and turning between partners, and several step patterns used to keep time. As musical tempos increased through the 1960s, with successive Motown hits by groups such as the Supremes, Four Tops, and Temptations, hand dancing style developed to suit the fast beat and new rhythms.

Like popular dance styles before and after it, hand dancing soon became a favorite pastime for teenagers and young adults. It largely eclipsed the older styles at house parties, cabarets, and clubs in Washington’s black community. DJs provided the music for dance events and built reputations on the breadth of their record collections and their skill in crafting song sequences.

Local television shows such as the Teenarama Dance Show, which ran from 1963 to 1967, featured local teenagers and put hand dancing in the spotlight. Individual dancers cultivated distinctive styles, often incorporating regional variations that developed within the city. Just by the way they danced, hand dancers could be recognized as hailing from Southeast, Southwest, or Northeast Washington. This intra-city variation, and the markedly contrasting dance styles seen on nationally broadcast shows like American Bandstand, helped to fortify local opinion that hand dancing was unique to Washington, D.C.

As the Motown era faded into funk and disco in the 1970s, however, hand dancing was largely replaced by “free dancing” styles, in which partners do not hold hands. Most of the black teenagers who had grown up hand dancing in Washington made an easy transition to the new free dancing styles, and kept pace as young adults with the new trends in popular black culture. Sometime in the mid-1980s, however, as rap became more commonly heard on the radio and hip-hop grew into a major cultural movement, hand dancers—by this time mostly in their forties and fifties—began to revive their generation’s “own” music and dance. This return to artistic roots planted firmly in the Motown era led to a revival of “oldies but goodies” music at Washington-area clubs, cabarets, and radio stations.

Hip-Hop

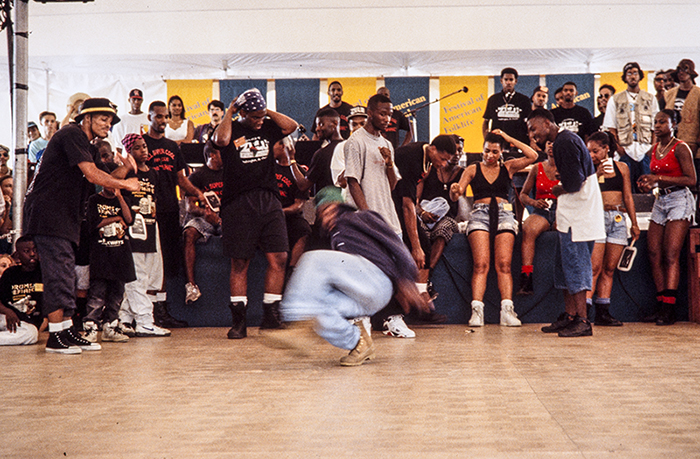

Hip-hop is not just a dance style; it is a multifaceted world of expression that includes dance, music, a DJ’s skilled mix of live and recorded sounds, verbal art (including rapping and other forms), visual arts (such as graffiti), clothing, body adornment, and social attitude. Hip-hop is shared by young people of different cultural backgrounds throughout the United States, but its basic aesthetic ideas are deeply rooted in African American culture.

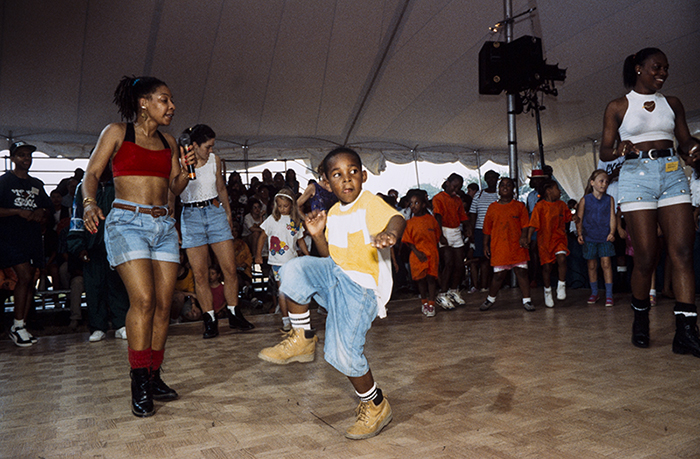

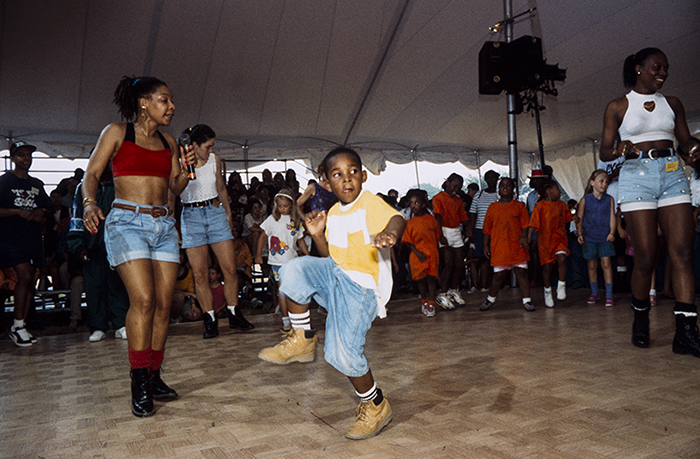

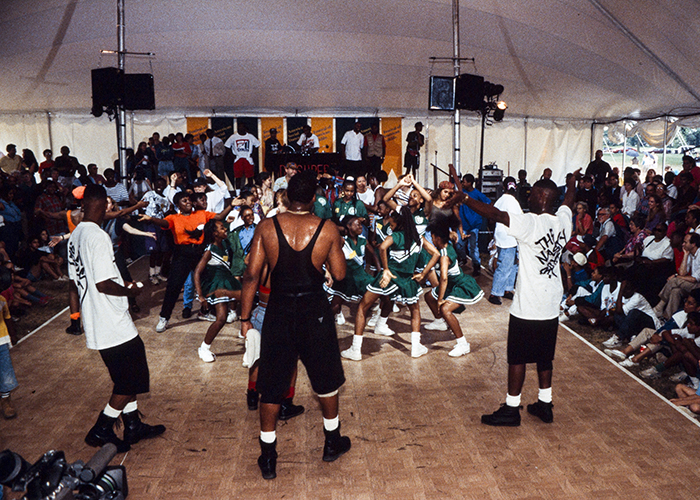

In Washington’s black community, hip-hop includes social dancing, done by couples (who do not hold hands); and exhibition dancing, done by individuals or sets of dancers who do their most impressive moves and choreographed routines to demonstrate their prowess.

Hip-hop dancing is done to any type of hip-hop music—rapping, singing, or instrumental—with an appropriate beat and tempo. This can also be unadorned rhythm playing, such as a synthesized drum track or an impromptu beat pounded out by hands or with sticks. Social dancing is most often based on relatively simple patterns of stepping and weight shifting, which are overlaid with multiple rhythmic layers of gestures done with the arms, head, and segments of the torso.

Exhibition dancing can include any move used in social dancing, but it features a wider repertoire of fancy stepping patterns; body waves and isolated movements of body parts (as in “popping”); gestures, facial expressions, and other forms of mimicry; acrobatic tumbling, splits, jumps, and spins; and choreographed routines that combine any number of different elements. Not all dancers choose to develop the extraordinary skills of exhibition dancing, but nearly everyone that participates in hip-hop does social dancing.

Dancing generally happens at clubs, cabarets, and parties that feature hip-hop music. But it can also erupt spontaneously in response to music in schoolyards, neighborhood streets, and homes. Often these informal performances are interspersed with mimicry and acrobatics.

Deejays are the favored source of music for hip-hop dance events. Like those in older generations in the black community, hip-hop DJs are valued for their skill in gauging the fit between the music and the dancers’ mood, for their ability to string together inspiring musical sequences, and for their collections of sound recordings and equipment that allows the greatest range of musical creativity. Most hip-hop DJs are also adept at “mixing,” a range of music-making skills including such techniques as “cutting” and “scratching” that involves the manual manipulation of discs on multiple turntables and the interpolation of additional sounds generated by synthesizers, electronic rhythm machines, pre-recorded tapes, verbal art performed by the DJ or others, and a variety of percussion instruments.

Go-Go

Though hip-hop culture provides the framework for much of the music and dance among young people in the black community, another style, one unique to Washington, D.C., provides an artistic alternative for many teenagers: go-go. Unlike hip-hop, which except for a DJ’s mixing uses pre-recorded music, go-go is danced to live bands that generally include multiple percussionists (playing a trap set, congas, and a variety of small, handheld instruments) and a mix of keyboard synthesizers, bass, horns, guitars, and vocalists. This “big band” sound is especially well-suited for large public venues such as clubs. The music is funk-derived and incorporates elements of Afro-Cuban and jazz styles.

Chuck Brown, the “Godfather of Go-Go,” at the 2000 Folklife Festival. Video by Charlie Weber

“Bustin’ Loose” by the Chuck Brown Band at the 2016 Folklife Festival. Edited by W.N. McNair

Go-go dancing has the same basic structure as hip-hop social dancing—stepping and weight shift patterns overlaid with multi-rhythmic arm, head, and torso gestures—but it is adapted to the slower beat and distinctive go-go rhythms. Though go-go and hip-hop dancing both draw on the same fundamental African American movement repertoire, go-go dancing has its distinctive patterns and frequently uses mimicry like that in movement play and exhibition dancing to generate new dances. Though go-go is very popular with teenagers in Washington’s black community, it has generally coexisted with hip-hop rather than replaced it altogether. Teenagers’ interest in go-go appears to fade as they near their twenties and return to the artistic frame of hip-hop.

Folklorist LeeEllen Friedland has studied European- and African-derived social dance traditions in the United States since 1975. She is director of Ethnologica, a Washington, D.C., consulting firm that specializes in folklife and cultural heritage research.