Introduction

By Juan Carlos

Holiday celebrations in our family always involve sharing the bounty of our Puerto Rican culinary traditions with our friends, extended family, and neighbors.

What started as a series of smaller, separate gatherings has snowballed into one large, evening-long open-house party with dozens of friends new and old coming and going. Though COVID forced us to pause the festivities for a couple of years, 2022 marks the full return of the event as well as the ritualized days of careful preparation.

Our party often announces itself to the neighborhood with the rich, smoky scent of pernil (pork shoulder) set to slowly roast and perfume the air outside for hours before guests are due to arrive. Once inside, our friends are greeted with the savory, earthy smell of arroz con gandules (rice with pigeon peas) and pasteles (a Puerto Rican Christmas specialty resembling large, rectangular steamed dumpling of grated plantain stuffed with savory meats) warming on the stove. Dessert always includes my great-grandmother’s flan de queso (cream cheese flan) and a tipple of my father’s coquito (coconut rum nog). Later on, once all the cleaning is done and the dishes are put away, the four of us will share some chocolate caliente (hot chocolate) before turning in for the night.

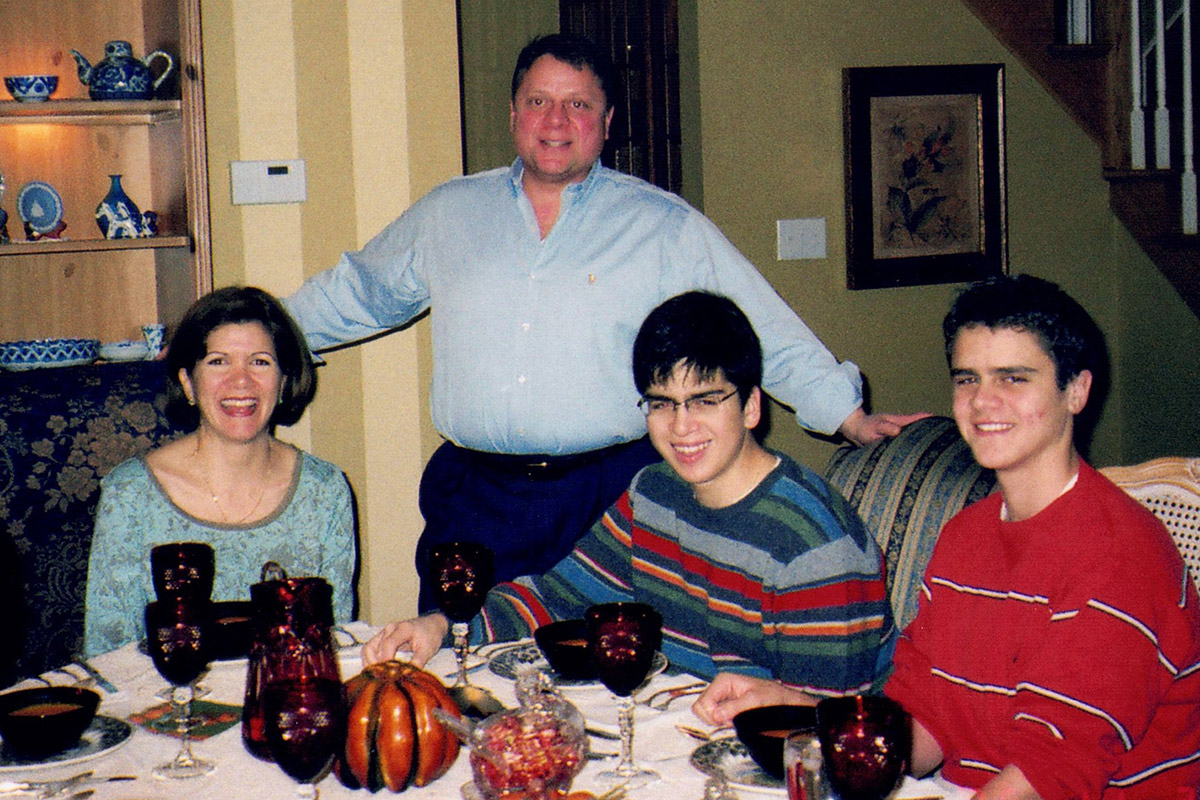

My parents, Elaine and Gerardo (“Gerry”), were born and raised in Puerto Rico but met in New Orleans in their teens while in college. They eventually settled in the Philadelphia area, where my brother G.J. and I were born. Our parents made great efforts to ensure that we were raised in a family that spoke Spanish and celebrated our Puerto Rican culture while remaining open to the emergence of new traditions through our shared diasporic experience. Food was, of course, a huge part of maintaining the connection to our heritage, and it continues to be a source of comfort and unity for all of us.

We couldn’t settle on a single recipe to stand as the sole representative of our love for the season, so we opted for four staples that we’ve been enjoying and perfecting for at least as long as my brother and I have been alive. The recipes below represent just some of our holiday traditions. Enjoy, and don’t forget to pair it with the Smithsonian Folkways Puerto Rican Christmas music playlist!

*****

Pernil (Roasted Pork Shoulder)

By Juan Carlos and Gerry

Many of the images representing a traditional Christmas dinner in Puerto Rico include lechón a la varita, very much like a whole turkey for an American Thanksgiving. Lechón a la varita is a whole pig traditionally seasoned and slowly roasted over an open pit with smoldering wood, resulting in meat with a light smoky taste and the much desired cuerito—crispy, fatty skin akin to a crackling.

A practical alternative to cooking a whole pig is to cook a pernil, a fresh pork butt or shoulder seasoned in a traditional marinade. The holidays are an opportunity for us to blend Puerto Rican and mainland traditions: we always have turkey and pernil for Thanksgiving and pernil again for Christmas. Our pernil preparation prioritizes getting the crispiest, richest cuerito while cooking the meat as close as possible to the traditional open-pit method.

The recipe below has evolved over many years of trial and error. We believe that optimum results can be achieved by cooking the pernil on a grill using wood chips to provide a smoky tang.

Here we provide two recipes, one for oven and one for the grill with wood chips. Count on one pound of meat per person.

Ingredients

10–16 pounds pork butt or shoulder with skin (not Boston cut, otherwise no cuerito)

½ cup olive oil

½ cup white vinegar

8 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon salt per pound of pork

Ground black pepper to taste

2–3 tablespoons dried oregano

Preparation

Rinse pork thoroughly with cold tap water. With a small sharp knife, lift the skin and fat as much as possible without completely removing the skin.

Prepare marinade by blending all the other ingredients. The ingredients can be adjusted to taste.

Place pork in a disposable aluminum pan and rub marinade all over, including under and over the skin. Place in the container skin side down. Cover with plastic wrap and marinate in refrigerator overnight.

On cooking day, remove pernil from fridge and let rest at room temperature for 1 hour.

OVEN METHOD: Preheat oven to 350° F. Transfer pernil to a roasting pan skin side up. Roast at 350° for 2 hours. Then lower to 325° and continue cooking until internal temperature of the meat reaches 165°.

GRILL METHOD: Preheat grill to about 350° F using indirect heat. Transfer pernil directly to the grates skin side up and insert meat thermometer. Roast at 350° until internal temperature reaches 165°. At the start and every 45 minutes or so, add wood chips for smoke until the meat reaches 120° or so. I usually use mesquite wood chips, but use what you prefer.

Total cooking time is about 20 to 30 minutes per pound, but make sure you check the internal temperature so that it reaches 165°. Remove from oven or grill, cover with aluminum foil, and let rest at room temperature for 1 hour.

Carve the meat and fend off the cuerito grabbers using the sharp carving knife.

*****

Flan de Queso (Cream Cheese Flan)

By Elaine and G.J.

This is an old recipe handed down from Elaine’s maternal grandmother; it is just one of many different versions of flan that exist throughout the Caribbean. This cream cheese-based version has a heavier and creamier texture than most others. This dessert has been the star of the menu at our Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner celebrations for decades.

Preparation is simplified by the fact that the main ingredients are packaged and readily available in the required proportions at most U.S. grocery stores. Preparing the caramel, the first step, may take some practice and experimentation since some people prefer the caramel lighter in color while others prefer a darker caramel with some burnt notes to counterpoint the sweetness of the flan. We recommend you enjoy some experimentation for side-by-side comparison.

Ingredients

1 cup white granulated sugar

1 can (14 ounces) condensed milk

1 can (13 ounces) evaporated milk

5 eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 box (8 ounces) cream cheese, at room temperature

Preparation

In saucepan, mix sugar with ½ cup water and cook over medium-high heat, stirring constantly, until it liquifies. Pay close attention since the caramel can darken quickly. Once the caramel turns the desired color, immediately pour into flan mold—a wide, low-sided ceramic baking dish, also known as a tart or quiche dish. Swirl the caramel around to cover the entire bottom surface and edges. Let cool so that it hardens.

Mix all other ingredients in blender and pour over the hardened caramel.

Place the flan mold in a water bath—a rimmed baking sheet filled with ½ inch of water. Cook at 350° F for 45 minutes.

When the top is light golden brown, remove from oven. It should be firm with a little jiggle. Let cool completely, then cover with plastic wrap and transfer to refrigerator.

When ready to serve, loosen borders with a knife and invert onto serving platter.

*****

Coquito (Coconut Rum Nog)

By Gerry

The unofficial Puerto Rican Christmas drink! No Christmas festivity in Puerto Rico is over until you get a small glass of coquito, sometimes with a dusting of cinnamon on top.

This recipe is very easy to make. It uses canned ingredients and requires minimal measuring since the entire contents of the can are used. It can also be easily adjusted: part of the fun is in experimenting to find the right proportions to meet your own preferences. If you like it less boozy, then reduce the amount of rum. Should you prefer a creamier texture, then increase the amount of cream of coconut. Looking for less sweetness? Just reduce the condensed milk and replace that volume with evaporated milk.

Ingredients

1 can (13.5 ounces) coconut milk (not the same as unsweetened coconut milk)

1 can (15 ounces) cream of coconut (not the same as coconut cream)

1 can (14 ounces) condensed milk

1 can (12 ounces) evaporated milk

1 cup rum

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

½ teaspoon cinnamon

Preparation

Add all ingredients in a blender and mix for approximately 2 minutes.

Bottle and refrigerate for at least 1 day before serving to let the flavors marry.

Serve cold in a shot glass or small tumbler. Optionally, sprinkle a dash of cinnamon on top.

*****

Chocolate Caliente (Hot Chocolate)

By Elaine and Gerry

As kids growing up in traditional Puerto Rican families on the island, our Christmas celebrations always emphasized its religious significance. Midnight Mass was one of those yearly events which required some level of enticement to get the younger members of the family to willingly come along. In our families, that enticement consisted of getting chocolate caliente (hot chocolate), usually served with pan sobao (a soft semi-sweet bread) and queso de bola (an Edam-like cheese sold in large spheres covered in red wax) at home after the mass. The bread and cheese was usually bought elsewhere, but the chocolate caliente was made at home. The chocolate used back then was Chocolate Cortés, which is still available in its original form and is the one we use at home two generations later.

This recipe renders a thick and rich hot chocolate that warms your body both inside and out. You can experiment with the amount of cornstarch to adjust the thickness. You can also replace some of the whole milk with evaporated milk to make it creamier in texture and taste. A bar of Chocolate Cortés consists of 6 chocolate “fingers” with each finger premeasured to one cup of milk. Thus, a whole bar will require 6 cups of milk, but you can easily reduce the amount by reducing the number of “fingers.”

Ingredients

1 Chocolate Cortés “finger” per serving

1 cup of whole milk per serving (or substitute some with evaporated milk)

Up to 1 teaspoon of cornstarch per serving

Preparation

Prepare a cornstarch slurry by mixing equal amounts of cornstarch and water. Set aside.

Break each “finger” into a few pieces and place in a saucepan with a little bit of water. Melt chocolate over medium-low, stirring constantly and being mindful that it doesn’t burn.

Add milk and continue to stir. May increase heat to medium and stir until no chocolate residue remains.

When the milk is close to its boiling point, slowly add the cornstarch slurry while continuously whisking to prevent the cornstarch from lumping. Continue stirring and adjust the temperature to keep the liquid close to the boiling point and cook for about 2 minutes. Serve and enjoy.

The Meléndez-Torres family includes Elaine and Gerardo and their sons G.J. and Juan Carlos. Elaine and Gerardo were born and raised in Puerto Rico and eventually put down roots in Pennsylvania. G.J. works as a professor of epidemiology in Exeter, England. Juan Carlos lives in Washington, D.C., and is the royalty analyst at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.