When I asked my grandmother, Ahuva, why she didn’t teach me Yiddish, she laughed. “It was not an option at all,” she told me. “At all.” Instead, she had given my brother and me simple Hebrew lessons, teaching us the names of colors as we traced the letters of the alphabet with our crayons.

When I’m home from college, I see Ahuva almost every day. We sit on the couch and talk. But this was the first time I had asked her about Yiddish.

I had always been told that Yiddish was part of the life my family left behind when they fled Poland, but lately I had been struggling with that one-sentence explanation. I couldn’t begin to imagine the frustration and isolation I would feel if I purposely cut myself off from speaking English. I knew there had to be more to the story.

“But why wasn’t Yiddish an option?” I prompted.

Ahuva folded her hands in her lap and sighed. In the pause before she spoke, we could hear the faint clinking of dishes, my mother cleaning up from lunch in the kitchen.

I didn’t need to ask my grandmother why her parents left Poland. After surviving the Holocaust, they tried to rebuild their lives in their hometown of Czarnów but found they were not welcome back. Their families were gone, Christian neighbors had taken over their homes, and they had heard stories of returning survivors being murdered out of hate or for their property. My great-grandparents, Yocheved and Ya’akov, took my great-aunt Ella and left Poland in the middle of the night. They lived as refugees in France until moving to Palestine in 1947, which at the time was a British-controlled territory.

Around six months after their move, the state of Israel declared its independence, leading to a bloody war. Israel was not the respite from violence that millions of Jewish refugees were seeking, nor was it a respite from the judgement of fellow Jews.

“There was not much respect for Holocaust survivors at the time,” my grandmother told me. “The idea was that the new Jews in Israel were fighters, not going to the slaughter, as they thought the Europeans did. Like the Bible, they said they were the people who were born in the desert and were never slaves.”

The Biblical story she referenced is set after the Israelites were freed from Egypt. Standing at the edge of the promised land, the Israelites were afraid to go to war with the Canaanites and refused to enter. God declared: “Not one of the men of this evil generation shall see the good land I swore to give your fathers.” The implication is that Jews who weren’t willing to both physically fight for Israel and sever themselves from their pasts were a disgrace.

“People didn’t want to speak Yiddish because they didn’t want to be recognized as Europeans,” Ahuva explained. “Many kids would not have been able to talk to their parents if they didn’t speak Yiddish. But if you could speak Hebrew, you did. Of course, I knew my parents were the best people ever, and whatever language they could communicate in was okay with me.”

Even though she didn’t personally consider Yiddish a source of shame, my grandmother adapted to her environment. Growing up from infancy in Israel, she had no problem learning Hebrew. Outside the house, she even changed her name from Liba, meaning “beloved” in Yiddish, to Ahuva, the Hebrew translation. Even now, my grandmother does not understand the gravity I place on this name change. “If you could, you did,” she said. “When you went to school, the teachers would do it for you.”

My own given name is Adi, an Israeli name meaning “jewel.” A few years ago, I started going by AJ—my initials. Especially after I admitted the constant mispronunciations that drove my decision, my grandmother saw my nickname as an affront. To her, I should be proud to go by an Israeli name. When I pointed out that she does not go by her given name either, she couldn’t see the connection. In fact, keeping her name would have felt counterproductive to her, even regressive. When she was growing up, she was taught that Hebrew was the language of the bright future, and Yiddish was the language of the dark past. In that era, Israelis were determined to heal not only from the Holocaust but from the shame they felt in the diaspora.

The dispersion of the Jewish diaspora was a gradual process, but it escalated after a series of devastating military defeats at the hands of the Romans in the first and second centuries CE. Jewish people scattered from what is now Israel across the world, splitting into cultural subgroups. Yiddish developed as the language of Ashkenazi (Central, Eastern, and Western European) Jews. At the same time, the Judeo-Malayalam language developed among Cochin Jews in Kerala, India, and Judeo-Spanish (also known as Ladino) among Sephardic Jews of the Iberian Peninsula.

Everywhere Jewish people settled, persecution followed. From segregation and banishments to massacres, many Jewish communities never felt safe. After the enormity of the Holocaust, some Jews felt that their only hope would be reuniting the Jewish people in a country of their own. They believed a return to pre-diaspora times was necessary, meaning diasporic languages and cultural traditions had to be renounced.

I sat back in my chair. Hearing my grandmother’s explanation, I understood that prioritizing Hebrew felt empowering, but I still couldn’t imagine choosing not to speak to my children in the language that was most immediate to my thought process.

In some cases, it was the younger generation who resisted learning Yiddish. I spoke with Rosie Kaplan, who now co-runs a virtual Yiddish discussion salon, about her experience moving to the United States as a child. “I tried to convince my parents that, you know—enough with the Yiddish already. If we’re going to be Americans, just drop the Yiddish,” she told me.

Judy Kunofsky, the executive director of KlezCalifornia, the Yiddish resource organization that hosts Kaplan’s monthly salon, shared a similar story. Kunofsky’s mother and father were Polish Jews who immigrated to Brooklyn in the 1910s and 1930s, respectively. Though Kunofsky now works to keep Yiddish education alive, her parents never spoke the language to her when she was a child.

“There was an association of Yiddish with death,” she told me. “The idea being that if you didn’t speak Yiddish, you would never die, in some deep psychological sense. The only people you knew who died were Yiddish speakers: people from the older generation and from the Holocaust.”

The decision to not teach their children Yiddish felt like a way of protecting them, of setting them up for success. “People used to think that if you learned two languages, you would have an accent in both of them, which is not true,” Kunofsky explained. “They were worried that my generation would grow up speaking English with an accent, which they thought would keep us back.”

Unlike most parents who did not speak Yiddish to their children, Kunofsky’s parents chose to send her to a Yiddish after-school program. “It was very bizarre that they didn’t even talk to me in the language that they sent me to school to learn,” she said. “But they sent me to the Workmen’s Circle”—a Jewish social justice and cultural engagement nonprofit—“which had a secular Yiddish school.” Though Kunofsky’s own parents emigrated to the United States before the Second World War, “a lot of the students there had parents who had been in the death camps. They thought that God couldn’t possibly exist if there had been the Holocaust, but they sent their children to Yiddish school because they still felt very Jewish.”

When people ask me if I’m Jewish, I don’t hesitate to say yes. If they ask me if I believe in God, my answer isn’t so immediate. Judaism has always been more than a religion: Jewish communities have their own cultures, languages, and ethnic makeups. Before World War II, almost every Jew in Europe could speak Yiddish, regardless of their level of religious observance. After the Holocaust, many survivors struggled with their relationship with Judaism. Some survivors lost faith in the existence of a god who would permit such suffering; others found crucial comfort in their faith. Religious observance and Yiddish language were aspects of Judaism, but turning away from either or both didn’t make anyone less of a Jew.

Today, the demographics of Yiddish speakers represent the evolution of the specifically European Jewish identity. Academic Yiddish is taught in universities all over the world, but, in everyday life, the largest group of people keeping vernacular Yiddish alive are Haredi, or ultra-orthodox Jews.

In the past, Jewish communities were treated as inferior and segregated into specific neighborhoods and professions. This isolation formed tight-knit communities, strong traditions, and the Yiddish language. Today, most Jewish communities are integrated into the secular world and therefore have less use for Yiddish. Many Haredi communities, on the other hand, find meaning in keeping themselves separate from wider culture and use Yiddish as a primary language.

Speaking Yiddish is not a part of my Reform Jewish community. The only people I know who speak Yiddish are my grandparents, but what they want is for me to improve my Hebrew. Nevertheless, I’m drawn to the idea of knowing the language my family spoke for so many generations.

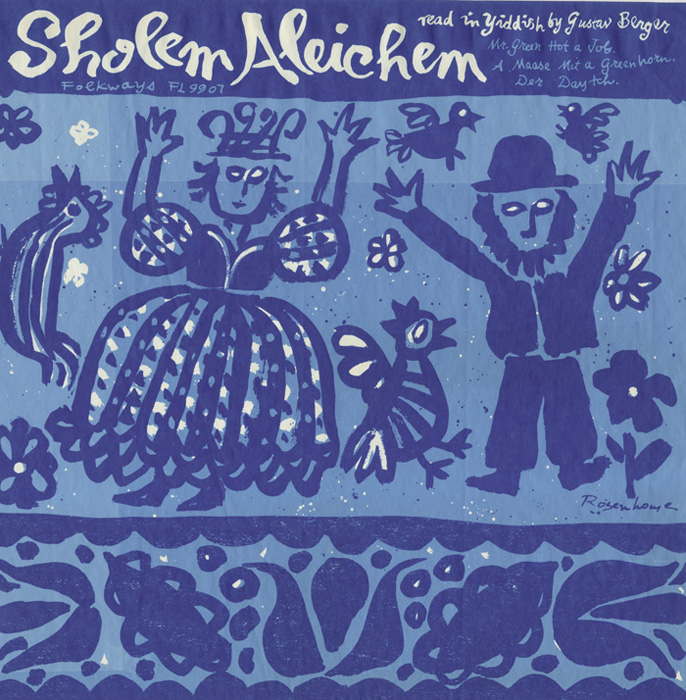

If I knew Yiddish, I could explore its long tradition of theater, fiction, and poetry without the boundary of translation. You might have heard of Fiddler on the Roof, the renowned Broadway show about Jewish life in turn-of-the-century Russia. The musical is based on author Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish short stories. Aleichem, along with I.L. Peretz, Mendele Mocher Sforim, and Sholem Asch—father of Folkways Records founder Moses Asch—is recognized as one of the great classical Jewish writers. I would love to read their work in its original form, appreciating all the carefully crafted wordplay. Yiddish has also long been a language of leftist political writing and is the most frequent language for Holocaust literature and testimony, much of which has not been translated into English.

Even if they were translated, some believe there would be something lost along the way.

“There are certain things that can only be said in Yiddish,” said Evie Groch, who co-runs KlezCalifornia with Rosie Kaplan. “When I’m talking to my non-Yiddish-speaking friends, I have to teach them the Yiddish word because I cannot get my message across otherwise.”

One such word is ganeganheit. “It means when you are happy for the joy that someone else finds in what they’ve accomplished,” Groch explained. “It’s more than pride because they may not be related to you, but you’re just so happy for their happiness.” She paused for a second to think and laughed. “Yeah, I can’t get it any closer than that. I consider Yiddish a language of endearment, a language of comfort, a language that I come home to when I hear it spoken.”

“Yiddish will never die because it has a special charm,” expressed Assia Azenkot, who runs another Yiddish conversation group. “It contains our heritage, our family, our bubbes and zaydes [grandmas and grandpas], our chicken soup and our kugel, our proverbs and our sayings. Yiddish is not only a language—it’s a culture and it’s a people. If it were a palace, it would be a palace with many doors that you can open and be welcomed.”

Not everyone I spoke to agreed that Yiddish carries an inherent emotional legacy. Dovid Braun, a linguist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, frowned when I asked how he feels about the resentment for Yiddish some felt because they associated it with the trauma of European Jewry.

“The same question could be asked about English,” he said. “Then you might be dumbfounded by that question because you’d say, ‘Gee. I don’t know,’ or ‘why would I even think in those terms about generalizations like that?’

“I’ve heard we associate Yiddish with women, not with men, but it takes two to tango and that’s how generations of Jewish children were born speaking Yiddish,” he continued. “I’ve heard we associate Yiddish with American theater—well, there’s a lot of theater that comes from Yiddish, but my family hasn’t been involved with theater. We associate Yiddish with great food or with ethnic food that warms your heart, but my mom couldn’t stand my grandmother’s cooking.”

Another common association with Yiddish is comedy. Many of the Yiddish words that have been integrated into English over the years are playful. We’ve all heard, and probably used, oy vey (an expression of frustration or dismay), to kvetch (complain), to shlep (drag something around), a mentsh (a good person), a shtik (a gimmick). Unconsciously, many Americans associate Yiddish sounds and words with inherent humor.

“When somebody uses a Yiddish word, I hear people laugh even when it’s not funny,” Judy Kunofsky told me. “But Yiddish isn’t, in itself, funnier than any other language. You can do King Lear in Yiddish. You can do tragedies in Yiddish.”

The idea that aspects of language—such as sentence structure, grammatical gender, and untranslatable words—shape their speakers’ perceptions of the world is known as linguistic relativity. The concept is interesting but lacks robust supporting evidence and can lead down a slippery slope into biased thinking. If we believe groups of humans inherently perceive the world differently, it places exoticizing boundaries between cultures, implying we can never truly understand people from different backgrounds.

Linguistic relativity aside, my grandmother insists that there is something inimitable about Yiddish that makes jokes exponentially funnier. When I asked her why, she responded that “humor comes from pain.”

“There’s always a seed of truth in jokes, which you turn around and make funny,” she told me. From her perspective, the hardships that have always followed the Jewish people give our language singular power.

As my curiosity led me into more and more conversations with Yiddish speakers, I found myself increasingly confused. Does Yiddish carry otherwise hidden truths of comedy or community? Is its smaller number of speakers something to mourn, or is it proof that our community can persevere and adapt to new circumstances? Would learning Yiddish honor my ancestors or disrespect their decision to leave it behind?

I’m not the only descendant of Yiddish speakers considering joining the Yiddish revival. Over the past few years, the number of Yiddish learners has grown immensely. The popular language-learning app Duolingo introduced a Yiddish course in 2020, which now boasts hundreds of thousands of learners.

YIVO has also seen a COVID-era spike in interest in their Yiddish learning programs. “In spring 2022, we had over five times as many classes as we had in spring 2020,” reported Ben Kaplan, director of education. “There are lots of different factors that contributed to this. People were home, they had more time, they had more flexible schedules, they were in a reflective mood. They were thinking about their lives, about what they want to do with their time.”

Kunofsky noticed this same phenomenon. “Yiddish culture is seen as new, which my parents would’ve thought was hysterical,” she said. “It’s thought of as transgressive, because it doesn’t deal with the three hot-button issues of Jewish life, which are Israel, God, and prayer.”

Back in my living room, I finish with my questions, and my grandmother finds space for her own. She asks how my college classes are going, whether I’m making lots of friends, why I don’t call her enough, and if there is anything I want her to buy me.

After she leaves, my phone lights up with a notification from Duolingo. The chipper cartoon mascot tells me it’s time for my daily Yiddish lesson. I learn how to say hello (sholem-aleykhem), and how to say thank you (a dank). One day, I want to take a formal Yiddish class through an organization like YIVO and really dedicate myself. But when the class is over, I don’t think I’ll mourn the fact that I’ll never be fluent. Instead of hinging on learning the language, the connection I’ve felt to my family’s past came from hearing the stories and experiences of scholars and speakers in the Yiddish community.

I used to see Yiddish as a mystery, and now I recognize how its culture has shaped my life today. I understand the journey my family history took, and I’m proud to be the product of it.

AJ Jolish is a former intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a creative writing major at Scripps College.