“[The Yiddish folk saying] ‘Tsu zingen un tsu zogn’ [To sing and to say]…derives from the time when the Jewish ‘Spielmänner’ (the Jewish minstrels of the Middle Ages) would recite their bardic tales set to a chant. In the Yiddish vernacular, it has come to mean a person who has a lot to complain about.”

—Ruth Rubin

This quote from a notebook of Ruth Rubin, the renowned Yiddish song collector and performer, demonstrates her knowing affection for and deep understanding of folklore in the Yiddish world and beyond. In it, we can get a sense of both her scholarship and wit.

Rubin was born in Khotin, Bessarabia, in 1906, and shortly thereafter immigrated with her family to Montreal, where she grew up immersed in secular Yiddish culture. Throughout her life, she had vivid memories of the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem visiting her shule (Yiddish day school). She moved to New York City at age eighteen and published Lider, a book of original Yiddish poems, in 1929.

In the mid-1930s, Rubin began studying and collecting Yiddish folksongs, following in the footsteps of British folk music pioneer Cecil Sharp.

She knew the cultural traditions of Eastern European Jews were at risk of being lost. The very survival of Yiddish (the language of Eastern European Jews)—inextricably bound to the transmission of folksongs, stories, and customs—was already a divisive topic of debate between various groups within the Jewish community, even before the Holocaust. This sense of impending cultural loss was exacerbated by the urbanization and industrialization of Europe and the mass immigration of Jews to North America.

In Rubin’s “lecture-recitals” (her self-styled programs of unaccompanied folksong woven with cultural and historical information, translations, and observations), she implemented Sharp’s idea (circa 1906): “The art musician practices his art of intention… He is a specialist and music is his trade… The folk singer is unconscious of tune, but conscious of words… his melodic alterations are unintentional and intuitive.”

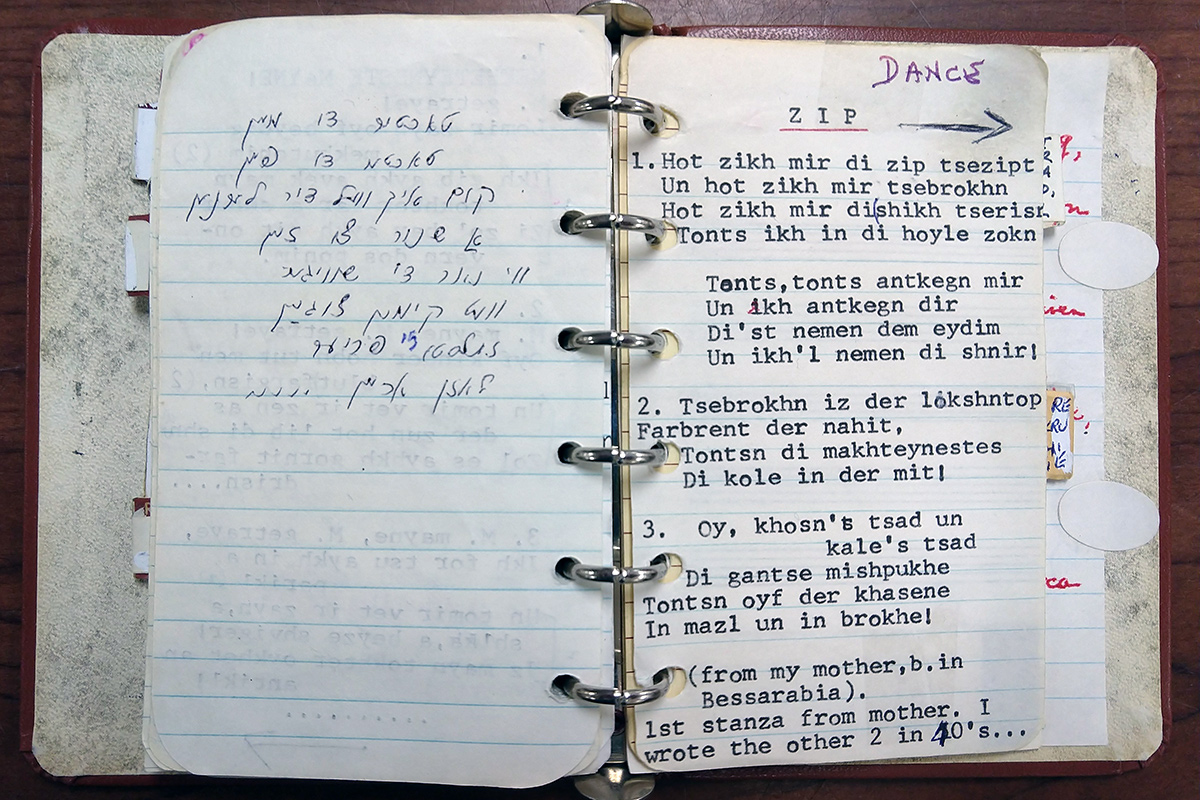

In an outtake from Cindy Rivka Marshall’s 1986 film A Life of Song: A Portrait of Ruth Rubin, Rubin introduces and performs “Hot zikh mir di zip tsezipt.” In her hands: this very notebook.

Rubin was a pioneer in the comparative study of folksongs and published several articles on this theme, as well as her groundbreaking book Voices of a People: The Story of Yiddish Folksong (1963). As she wrote, “Comparing the folksongs of different ethnic communities is a rich and rewarding experience: we share in the differences of the language, music, history, culture, geography—along with the universality of human experience—human characteristics, which are fundamental and common to all.”

Drawing on the repertoire of songs she collected, in the 1940s Rubin made her first studio recordings as a vocalist for Asch Records. Label owner Moses Asch later founded Folkways Records—now Smithsonian Folkways—which issued a large amount of Jewish material, including more of Rubin’s commercial output and an anthology drawn from her field recordings.

Around the same time, Rubin purchased a Wilcox-Gay portable transcription disc recorder and, in 1947, began documenting traditional Yiddish singers primarily in New York City and Montreal. Switching to magnetic tape in the 1950s (which, in addition to improving audio fidelity, did away with the time restrictions of recording to disc), Rubin eventually amassed a collection of over 2,500 Yiddish folk songs. The collection is now available through the Ruth Rubin Legacy online exhibition of the Max and Frieda Weinstein Archive of Sound Recordings at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, an organization dedicated to the preservation and study of the history and culture of East European Jewry worldwide.

According to her own testimony, the bulk of Rubin’s collecting was accomplished in tandem with her ongoing series of lecture-recitals, delivered at libraries, Jewish community centers, and retirement homes in North American cities. She encouraged local presenters to alert audience members that, after her presentation, she would interview and record the Yiddish song repertoires of anyone interested in singing for her. In this way she was ingenious in identifying and documenting some of the most remarkable traditional Jewish singers of the twentieth century, including the beloved Montrealer Harry Ary and Vilna partisan Shmerke Kaczerginsky.

An iconic part of Rubin’s live performances were the small, handheld, loose-leaf binders she consulted during her performances for song lyrics, translations, quotes, and historical information. Some two dozen of Rubin’s notebooks survive in her collection at YIVO and provide a fascinating glimpse into her way of organizing and presenting folk material to the audiences of her time.

The unassuming brown plastic binder entitled “WOMAN” was an integral part of Rubin’s recitals of Yiddish songs centered on the Jewish woman’s experience. This theme also inspired her doctoral dissertation, Jewish Woman and Her Folksong. In the course of her performances, she would nonchalantly consult the scrupulously typewritten pages of the notebook. The binder was divided by tab cards into themes: Child, Work/Poverty, Love, Khasene (Marriage), Traditional and Rekrutshine (Recruitment).

As Rubin wrote in her dissertation, “Little has been written on the history of Jewish women… Where, in previous periods, Jewish songs by women had been generally created for them; this time, women were creating their own songs, about their own life and the life around them… in their own vernacular, Yiddish, and on their own terms, they were speaking their heart and mind, at last.”

Rubin’s “Woman” program included the Yiddish folk song “Hot zikh mir di zip tsezipt” (“My sieve is all worn out”), titled in the notebook simply as “Zip.” The song featured prominently in Rubin’s repertoire; not only did she record it twice for her collection, she also committed three commercial versions to tape: one accompanied by none other than American folk singer and social activist Pete Seeger on the banjo. The song was published three times, and Rubin even wrote an English-language hoedown adaptation, “Wedding Hop.”

In a glowing review of Rubin’s December 4, 1965, lecture-recital at New York’s Town Hall, New York Times music critic Robert Shelton opined, “Miss Rubin sang her well-culled material in an expressive, warm and well-controlled alto range. This was not a display of vocal skills, nor was it meant to be. It was, rather, an affectionate and knowing recital of rarely heard folk material done with care, proportion and obvious involvement.”

“Hot zikh mir di zip tsezipt” takes its melody from a sher (klezmer square dance) tune quoted in Rumshinsky’s Bulgar, a composition by Yiddish theater composer Joseph Rumshinsky. Rubin learned the song from her mother, Rachel Grover-Spivack, who only remembered one verse in her Bessarabian Yiddish dialect, reflected in Rubin’s transcription. In what she called “a true folk process,” Rubin admitted to having written the second and third verses herself. These added couplets are drawn from folk motifs common in other songs and in the improvisational badkhn (Yiddish wedding jester) tradition of satiric rhyming. The song’s upbeat dance rhythm, catchy melody, and infectious lyrics made it a favorite with both Rubin and her audiences.

The text and translation follow:

Yiddish

Hot zikh mir di zip tsezipt

Un hot zikh mir tsebrokhn.

Hot zikh mir di shikh tserisn,

Tants ikh in di hoyle zokn!

Refrain:

Tants, tants antkegn mir,

Un ikh antkegn dir.

Du vest nemen dem eydem,

Un ikh vel nemen di shnir.

Tsebrokhn iz der lokshntop,

Farbrent der nahit.

Tantsn di makheteynestes,

Di kale in der mit.

Khosns tsad un kales tsad,

Di gantse mishpokhe,

Tantsn af der khasene,

In mazl un in brokhe!

English

My sieve was worn out,

And altogether broken.

My shoes were torn,

So, I’m dancing in my stocking feet!

Refrain:

Dance, dance facing me,

And I’ll dance facing you.

You’ll take the son-in-law,

And I’ll take the daughter-in-law!

The noodle pot has broken,

And the chickpeas are burnt.

The mothers-in-law are dancing

With the bride in the middle.

The relatives of the groom and bride,

The whole family,

Dancing at the wedding,

In good fortune and in blessing!

In an unpublished written statement, Rubin sums up her mission: “In our multiethnic, multicultural society, among whom many no longer speak, read, nor understand their root language, the preservation and transmission of such cultural materials is essential. In Yiddish, a language more than a thousand years old, the greater part of this rich song-literature remains to be gathered and made accessible to our English-speaking society. This realization and its urgency has influenced my work since the 1940s, affecting the patterns, content and direction of my teaching, research, lecture-recitals, authorship and recordings.”

From the example of a single page in a small brown notebook, it’s possible to discover and admire the resourceful creativity of this folklorist at play: as a tirelessly dedicated collector, performer, writer, translator, and transmitter of Yiddish songs. From her field recordings to her books and lecture-recitals, the importance of Ruth Rubin and her life’s work cannot be overstated. Her legacy lives on as it inspires those who learned from her and continue to pass it on through workshops, concerts, and new projects worldwide.

Lorin Sklamberg is YIVO’s sound archivist, and Eléonore Biezunski is the associate sound archivist in the Max and Frieda Weinstein Archives of Recorded Sound at YIVO. For nearly a century, YIVO has pioneered new forms of Jewish scholarship, research, education and cultural expression. The YIVO Archives contains more than 23 million original items and YIVO’s Library has over 400,000 volumes—the single largest resource for such study in the world.