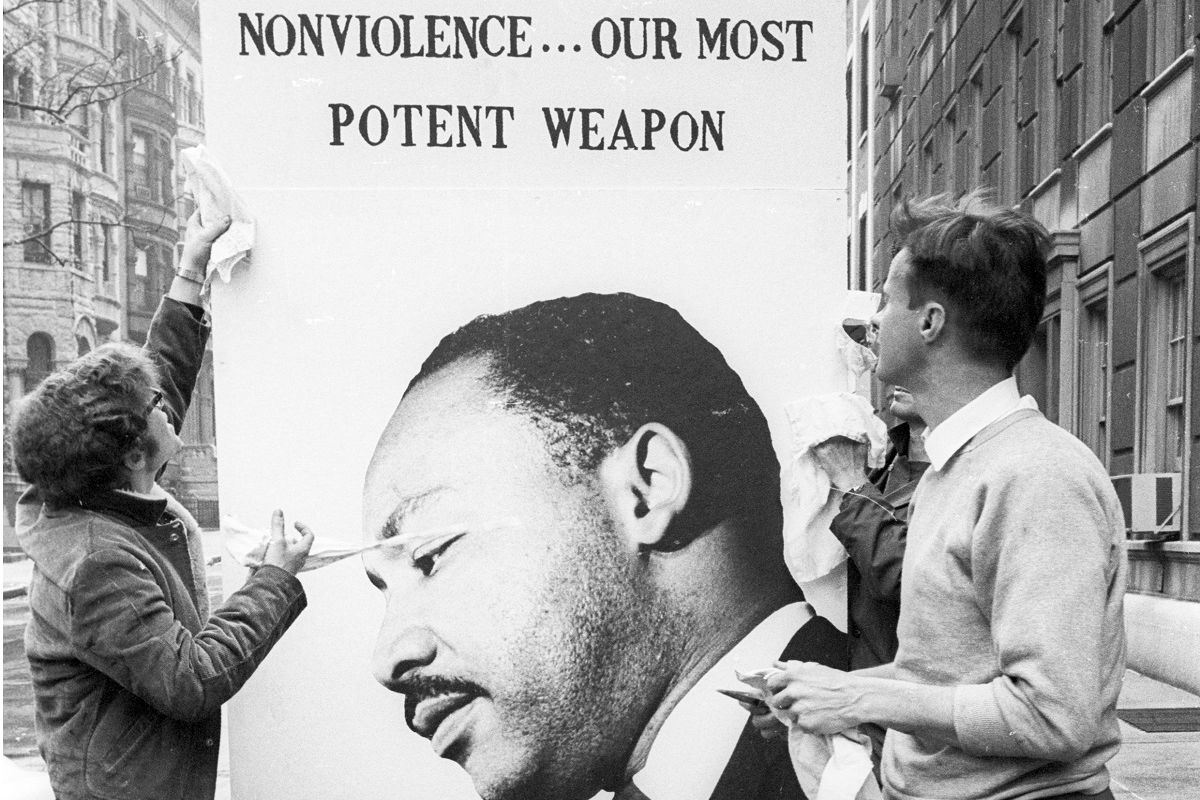

Media coverage of the movement for rights and justice exploded during the latter half of the twentieth century. The most dramatic images of the black freedom struggle centered on peaceful African American protesters being brutalized by police dogs, water cannons, and crowds of angry whites in the Deep South. Now, as then, the unwavering calm of the demonstrators in the face of ugly verbal and physical assaults is directly attributed to the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s guiding philosophy and practice of nonviolent direct action.

We should rightly extol the extraordinary courage of King and the countless individuals who laid their bodies and lives on the line in order to make the dream of an equal and just society for all citizens a reality. In particular, we must acknowledge the generations of ordinary African Americans who were engaged in struggle, well before the advent of “The Movement.”

Accordingly, focusing solely on the pacifism of the protesters—as though everyone marched in lock-step with King under the banner of nonviolence—narrows our historical understanding of the complexity and dynamism of the struggle. The contrasting perspectives and arguments among participants regarding strategy, tactics, and approaches needed to achieve those goals get written out of linear narratives that focus on successes and failures.

Interviews with activists in the struggle conducted for the Civil Rights History Project—a congressionally mandated initiative of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress—bring to the surface profoundly ambivalent views regarding nonviolence and provide a more nuanced picture of the freedom struggle. We present a few of those perspectives in excerpts below.

Nonviolence was a long-standing approach of King. He articulated this stance most publicly when arrested during the Birmingham campaign undertaken to desegregate the city’s institutions and places of business in 1963. In the famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” ostensibly addressed to white Birmingham clergymen who opposed the campaign, King also addresses “white moderate[s]” who urge a cautious, go-slow approach to desegregation and change. He begins the letter by noting that unrelenting white opposition to the campaign has left the protesters no alternative but to engage in “[nonviolent] direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community.” He goes on to state the moral imperative behind such protests is to engage injustice, but peacefully, and that the practical purpose behind the philosophy of nonviolent confrontation is to “create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.”

Excerpts from interview with Wyatt T. Walker conducted by David Cline, 06-20-2014 (AFC 2010/039: CRHP0109)

In these excerpts from a 2014 interview with David Cline, Reverend Wyatt T. Walker, a key member of King’s staff on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, recalls his year-long work to organize the Birmingham campaign. He addresses the necessity of confrontation in nonviolent struggle, for the violent reaction from white supremacists was then captured by the media for all to see. He also speaks of transcribing “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and reflects on the impact of the letter on public consciousness, terming it the modern-day equivalent of President Lincoln’s nineteenth-century affirmation of human equality and national character as set out in the Gettysburg Address.

The “tension” that the elders in the movement sought to create through nonviolent direct action in broader society was also present within the coalition of groups that mobilized under the umbrella of the freedom movement. Not all activists were equally convinced of the nonviolent approach as “a way of life” but came to reconcile with the concept and employ it as a tactic in the field.

In the following excerpt, Chuck McDew, then a South Carolina college student, speaks to the tensions that emerged at the first organizing meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on the Shaw University campus in Raleigh, North Carolina, in spring 1960. McDew candidly expresses the dubiousness of several people present at the time that Mahatma Gandhi’s pioneering practice of the principle of nonviolent resistance (satyagraha) and moral appeals to persecutors could gain any traction in an “amoral society,” particularly the Deep South of the United States.

Excerpts from interview with Charles F. McDew conducted by Joseph Mosnier in Albany, Georgia, 2011-06-04 (AFC 2010/039: 0021). Watch the full-length interview with Charles McDew.

Courtland Cox, another founding member of SNCC, notes his reservations in the excerpt below, pointing to the contrasting positions held by the delegation from Washington, D.C.’s Howard University and those from colleges in Nashville, Tennessee. In the segment of his interview presented here, he references Diane Nash and John Lewis, two student stalwarts of the movement, and the Reverend James Lawson, who was their mentor. Lawson was also an inspiration for King because of his deep knowledge and practice of Gandhian philosophy married to a radical Christian pacifist stance.

Excerpts from interview with Courtland Cox conducted by Joseph Mosnier in Washington, D.C., 2011-07-08 (AFC 2010/039: CRHP0030). Watch the full-length interview with Courtland Cox. Viewers interested in the history of radical Christian pacifism in the United States will wish to consult this webcast of a 2009 lecture at the Library of Congress by Joseph Kip Kosek, assistant professor at George Washington University.

The argument about philosophy, tactics, and strategy became enormously more complicated when student volunteers and others went from North to South to make common cause with locals in the freedom struggle. Once there, they ran headlong into white supremacists and officers of the law who actively used violence and other coercive tactics against local African Americans and also against the “outside agitators.” Simultaneously, the new arrivals had to reconcile with the fact that their embrace of nonviolent philosophy and tactics was often at odds with the historical legacy of self-defense practiced by African American community members, many of whom carried guns to ward off their oppressors.

The irony that nonviolent activists were often protected by armed African Americans—some of them members of the Deacons for Defense and Justice—was eye-opening for many of the young people. Charles Cobb, journalist, educator, and SNCC activist, has written marvelously about this often overlooked aspect of the freedom struggle in his book, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (2015). His book talk at LOC, followed by a discussion with Rex Ellis, NMAAHC’s associate director for curatorial affairs, can be viewed on this LOC webcast.

King’s unswerving commitment to nonviolence as a way of life ended in unspeakable violence at the Lorraine Motel fifty years ago in April 1968. For many since then, it has remained an open question as to whether and when his dream of justice, equality, and freedom will be achieved. It is worth remembering that King himself had no illusions that such goals would or could be reached without long, hard struggle—albeit one conducted with love and in peace. Accordingly, we would do well to reconsider his words at the conclusion of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1965. One phrase in particular from his address speaks directly to the thrust of his whole life and career:

And so I plead with you this afternoon as we go ahead: remain committed to nonviolence. Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man, but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.

In concluding his remarks, he paraphrases Theodore Parker, the nineteenth-century Christian minister and abolitionist, and reminds present and future audiences, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Guha Shankar is senior folklife specialist at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and director of the Civil Rights History Project. His work involves initiatives in documentary production, field-methods training, educational outreach, and cultural heritage repatriation with Native American communities.

Kelly Revak is an archivist at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress who is cataloging new interviews for the Civil Rights History Project. She is also working on the Occupational Folklife Project, the Ethnographic Thesaurus, and the Ancestral Voices project.