The early years of the Folklife Festival prominently featured a series of programs showcasing “Old Ways in the New World,” which began in 1973 and continued through 1981. What these programs typically brought to the National Mall were Americans of European descent who demonstrated both the continuity and change of their cultural heritage from the Old World of Europe to the New World of the Americas. In some instances, the “old ways” of Africa and Asia were also presented, but the emphasis was distinctly European.

Recognizing the need for greater diversity, the Smithsonian created an African Diaspora Advisory Group (ADAG) under the leadership of Folklife Festival assistant director Gerald Davis. In December 1973, ADAG issued its first report: a ten-page document titled “African Diaspora: A Folklife Festival Concept.” Maintaining that “presentations of African-american [sic] materials during the past seven years of the Festival of American Folklife have been relatively unsuccessful as cultural statements,” the document proposed “the concept of the African Diaspora … as a coordinative structure and a unifying philosophy.” The immediate results were a two-week pilot program on the African Diaspora at the 1974 Folklife Festival, followed by an even more ambitious two-week program at the 1975 Festival, and culminating in a twelve-week program for the Festival in 1976 to mark the U.S. bicentennial.

According to Smithsonian historian and curator Fath Davis Ruffins, the significance of these three programs cannot be underestimated. In her essay “Mythos, Memory, and History: African American Preservation Efforts, 1820-1990,” Ruffins wrote, “Perhaps for the first time ever in American public history, a Black American mythos—the notion of the unity of African peoples across time and space—was presented by a preeminent cultural institution.” She also noted that this may have been “the first government use of the term diaspora to name this version of Pan-African connection.”

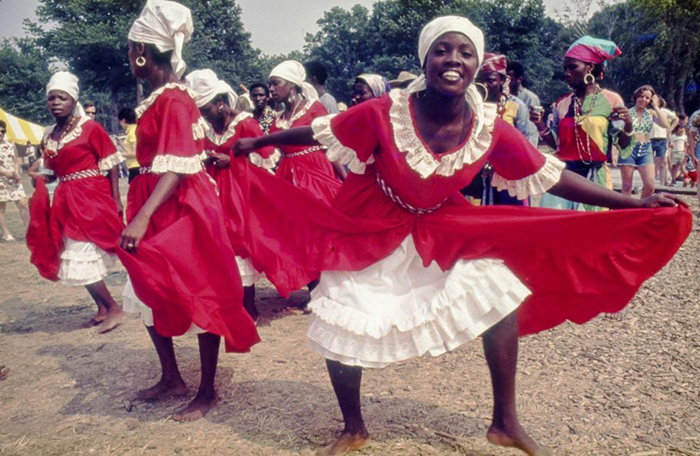

The African Diaspora programs sought to demonstrate the continuities of traditions and cultural heritage from the African world to the Americas. The 1974 Festival hosted basket weavers, cooks, dancers, fishnet makers, hairdressers, musicians, and woodcarvers representing diasporic traditions from Ghana, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States. The program book called attention to the similarity of basket making traditions in South Carolina, Mississippi, and Trinidad and Tobago; the similarity of culinary traditions—particularly okra and collard greens—from Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Ghana; the similarity of musical traditions from West Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States, particularly the blues, jazz, and gospel found in the latter; and the similarity of dance traditions, noting how the “traditional African use of the body in their high festival days and religious ceremonies are found in the jerk, cha cha, mambo, black bottom, the lindy, and the jitterbug” and “in the songs and ceremonies of the traditional Black church: rural Baptist, urban holiness and congregational.”

Similar connections appeared in the 1975 program, with dancers, fishnet makers, hairdressers, musicians, and woodcarvers representing Ghana, Haiti, Jamaica, and the United States. The program book pointed out similarities among country and urban blues in the United States with “the comparable African music of Salisu Mahama from northern Ghana,” as well as other commonalities in children’s games, cooking, hair braiding, sacred ceremonies, and basket weaving, noting the similarities in technique and materials among craftspeople from South Carolina, Ghana, and Jamaica.

Newspaper articles reinforced the exact aims of Festival organizers to draw connections among participants from throughout the African diaspora. For instance, Joel Dreyfuss’s article “Cultural Parallels at the Diaspora” in the July 4, 1975, issue of the Washington Post observed pluralism and cross-cultural connections on America’s 199th birthday: “[T]he various cultures, out of touch for several hundred years, have been brought together again in an atmosphere which attempts to recreate the marketplace of the Caribbean or West Africa. In its most successful moments, the only anachronisms seem to be the Lincoln Memorial in the background and the sound of jetliners on their final approach to National Airport.”

In retrospect, the African Diaspora programs at the Folklife Festivals in 1974, 1975, and 1976 served three very important functions:

1. They introduced the very notion of an African diaspora to millions of Festival visitors, serving not only to dispel notions of Africa as exotic, but also to highlight the contributions of African culture to everyday American life.

2. They helped to foster greater unity and dialogue within the diversity of African diasporic cultures.

3. They set a dynamic and engaging model for future Folklife Festival programs that has continued to the present.

The first function was very nicely illustrated by an example of making the exotic familiar and forging cross-cultural connections. As described by Dreyfuss: “Out in the marketplace, two pots of black-eyed peas are being ladled out to the public. One of the recipes is Ghanaian and includes pieces of fish, palm oil and red peppers. ‘It tastes just like the stuff I’ve been eating all my life,’ says a surprised black American. A woman peers curiously at the cup of Afro-American beans she has just been handed. ‘What is it?’ she asks Lynn Whitfield. ‘Black-eyed peas,’ says Mrs. Whitfield. ‘What do you call it?’ the woman insists, expecting an exotic name. ‘Black-eyed peas, ma’am,’ is the patient response. ‘Oh,’ says the startled black woman. ‘Black-eyed peas.’” In other words, black-eyed peas in Ghana look and taste just like black-eyed peas in the United States.

The second function of fostering unity and dialogue takes many forms, on and off the National Mall. Washington Post reporter Michael Kernan described the camaraderie between the 1975 Folklife Festival participants: “You should have been here the night the Italian-Americans got to the student center—four hours on the bus from New York—and here was this bunch of Ghanaians with their drums and they were dancing with some Germans, and this little old German guy about 5 feet tall was dancing with a 6-foot Ghana woman in her robes, holding hands and prancing around on the parking lot. … It’s been that way for two whole weeks at Marymount College in Arlington, where more than 600 Folklife Festival people from all over the world are living.” (“Camaraderie at the Festival Millenium [sic],” July 6, 1975.)

The third function of creating a model for future programs may be less tangible but is no less significant in measuring the legacy of the African Diaspora programs. Their influence is easily visible in numerous Festival programs with strong diaspora components that have taken place ever since the 1970s—from Black Urban Expressive Culture from Philadelphia (1984) to Cape Verde (1995) and African Immigrant Folklife (1997), and Kenya: Mambo Poa (2014) to Perú: Pachamama (2015).

James Deutsch has curated half a dozen Smithsonian Folklife Festival programs since 2005, but has experienced the African Diaspora programs primarily via the memoranda, notes, correspondence, and reports now residing in the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Interns Marguerite Quirey and Joshua Cicala provided invaluable research assistance.