Wa’e’ xtinutz’ib’aj jalal kitzij je nab’ey qatata’, qamama’ je ri xeb’oso winäq ojer.

“Here I will write some of the words of our first fathers, our first grandfathers, those who engendered the people long ago, from the Kaqchikel chronicles.”

In the midwestern highlands of Guatemala, there are currently around 800,000 Kaqchikel people. Unfortunately, only about half of us still speak the Kaqchikel language. Most of the speakers are adults and elderly people. Every year, there are fewer and fewer children who learn to speak it.

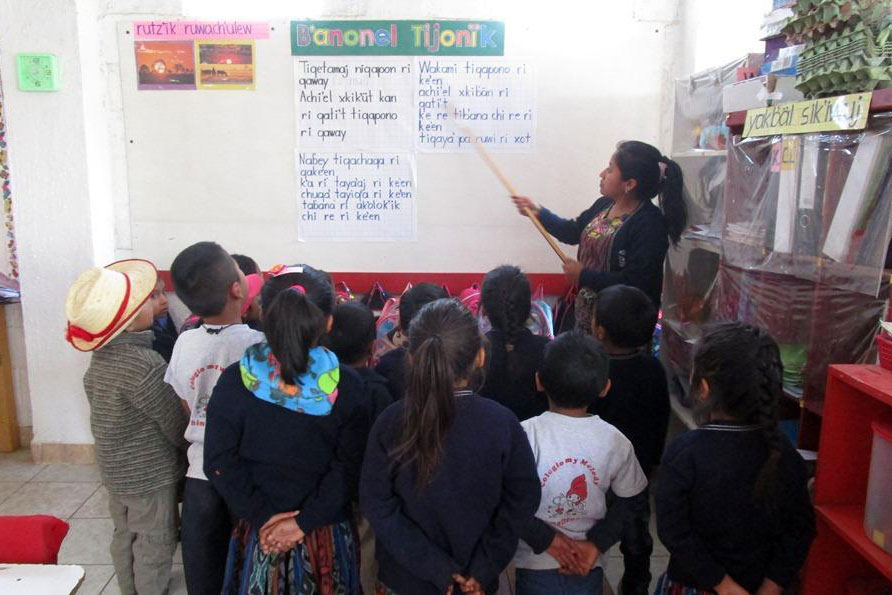

I am from the Maya Kaqchikel community in Chimaltenango, Guatemala, and I am the principal of a Kaqchikel language immersion school located in my hometown called Nimaläj Kaqchikel Amaq’. The aim of the school is to provide an education based on the interests and needs of the Kaqchikel people, so that the children in our community can break cycles of poverty and have a better future.

Starting the School

In my family, the last people to speak Kaqchikel were my grandparents. They decided not to teach the language to their children due to the discrimination they would suffer. My father, aunts, and uncles understand it but cannot speak it. My fifty cousins and I never heard one word of Kaqchikel as children. This transition from our native language to another happened not only to my family but to all neighboring families. As I grew up, I watched the death of the Kaqchikel language in my town.

In 2001, my family had the idea to establish a school where the children in our community could learn to speak the language of our ancestors, to understand our culture and traditions, and to feel proud of their identity and Maya heritage. This is how our small school, Nimaläj Kaqchikel Amaq’, was born.

There were many obstacles to overcome at the beginning of the project, but as people say here, “kakikot ustape’ k’o k’ayewal (be happy even though there is trouble).” When we told the teachers that we wanted them to teach all the subjects in the Kaqchikel language, they said that it was impossible to speak only in Kaqchikel to a child who only understands Spanish (the dominant language in our country). As a trial demonstration, we gathered a group of people who did not speak Kaqchikel, and we successfully taught them a series of lessons entirely in the Kaqchikel language. After this experience, the teachers were convinced it could be done.

We started teaching the four- to six-year-olds to read, but we did it directly in Kaqchikel. In one of the parent-teacher meetings, one of the mothers got up and complained. She said that children would not be able to read street signs, newspapers, or books since they are all written in Spanish. But the Kaqchikel alphabet is very similar to the Spanish alphabet, so when the children learn to read in the Kaqchikel language, they automatically learn to read in Spanish as well. In a few years, the parents noticed that their children also knew how to read and write in Spanish. Since then, they have been a lot more supportive of learning Kaqchikel.

In November 2022, our school had its first high school graduate, who came to our school when they were four years old. At eighteen, they were not among our top students at the Kaqchikel immersion school, but they nevertheless excelled by the national evaluation standards.

The Guatemalan Ministry of Education manages a standardized evaluation for all high school graduates in math and Spanish reading comprehension. The national average for Spanish reading comprehension is 20 percent. Our graduate received 73 percent! Even though roughly 10 percent of their reading consisted of Spanish materials, the student scored above the national average. Even though our first graduate received most of their education in the Kaqchikel language, they got better results in Spanish than students who received all their education in Spanish. It has been suggested that bilingual students generally have stronger reading comprehension skills, so the results were no surprise to the school staff. In fact, there was an even bigger contrast in the math category: the national average is around 10 percent, but our first graduate earned 86 percent.

With these results, the parents, students, and people in our community are more convinced that an education in an Indigenous language is just as good as—if not better than—monolingual education in Spanish. It reinforces our identity, especially in Guatemala where there is a lot of discrimination against Maya people. Our students don’t experience that inside our school, making for a better learning environment for all.

Building Curriculum

As we built our curriculum, we encountered another challenge: many modern words do not exist in the Kaqchikel language. For example: plastic pipe, helicopter, convection, photocopy, refrigerator, laser beam, etc. To solve this problem, we created words. For “plastic pipe,” we referred to our culture to find something resembling a pipe. It turns out that our ancestors used a blowgun, which they called pub’,to hunt for birds. So, we created the word t’im pub’ (“plastic blowgun”) to refer to plastic pipe. For “helicopter,” we use ch’ich’ tz’unün (“metal hummingbird”). For “photocopy,” we use kwachiwuj (“twin papers”).

In this way, we have managed to create words that we need in order to teach everything in the Kaqchikel language. Every so often, we send our new words to the Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala so they can be checked and corrected.

Our goal is to be able to teach all subjects in the Kaqchikel language within the next two years! This will be a huge accomplishment for us. Right now, Kaqchikel is largely used to discuss subjects such as farming and home life, but for the first time, our students will be able to use Kaqchikel to talk about computers, science, history, current events, and other modern topics. The table below shows the subjects we teach from preschool through high school. Those in green are subjects that we can currently teach in Kaqchikel. Shown in orange are subjects that we can almost teach entirely in Kaqchikel but are still lacking some educational materials. Everything in yellow cannot yet be taught in Kaqchikel. While preschool students begin their education in the Kaqchikel language from day one, high school seniors receive only about half of their lessons in the language.

Subjects like physics, biology, and chemistry are complicated to teach, especially in a second language, due to the large amount of technical terms. But even teaching them only partly in Kaqchikel is a huge accomplishment; first we had to create all the technical words, then teach those words to the teachers, then teach those words to the students.

We also have to make all these subjects interesting to the students. For example, when the physics class discussed vectors—quantities with both magnitude and direction—the teacher designed a competition in which each student built a bridge using only one hundred popsicle sticks and glue. Once the students built their bridges (using the theory of vectors to make them strong), we applied increasing weight to them until they collapsed. The whole school came to watch the competition, and now vectors are among the favorite subjects for our high school students.

So, not only are we able to teach these subjects in the Kaqchikel language, but we are able to teach them in a way that students actually appreciate! This is one of the main reasons our students achieve impressive abilities in all school subjects.

Dreaming Forward

While our students learn to read in Kaqchikel, there are very few books written in Kaqchikel for them to practice their new skill. We decided to create our own reading materials based on stories from our community. Already, our teachers have written over a thousand stories which our students can now use to practice their reading skills and, at the same time, learn about our culture and history.

An example text that we use is a story that takes place in the time before cars, in a small village in Guatemala. In those days, people would walk to the closest town to sell their goods, such as chickens. In one of the rest stops, a rooster manages to escape his basket and runs into the forest. Below is the first paragraph from this Kaqchikel text.

Ri mama’ äk' xsach chupam ri k’ichelaj

Ri nuxikin wati’t nutzijoj chi ojer kan, rije’ jantape’ jukumaj yeb’e pa tinamït Chixot richin nikik’ayij jujun taq ch’uxtäq; rik’in ri pwäq nikich’äk nikilöq’ jub’a’ atz’am chuqa’ jub’a’ tzakon kab’, k’a ri’ yetzolin pa kochoch richin yeb’e jun mul chik pa samaj.

The rooster got lost in the forest

My grandmother told me that many years ago, the people traveled very early to the town named Chixot to sell their goods. With the money they earned, they bought some salt and sugar, then they returned home so that they could continue working.

Some of our older students have begun writing stories for the younger students. The story below is about a bear who looks everywhere for honey. This exercise shows that our students are confident in their speaking and writing skills, to the point that they, too, make contributions in the revitalization of our language.

Our class of fourteen- and fifteen-year-old students understand everything their teachers say to them in the Kaqchikel language and are able to answer questions in Kaqchikel. They are among the few Kaqchikel people who can read and write in our language. Often, they speak with each other in Kaqchikel. This is a powerful indicator that the students identify with the language, and it is not just a language that they have to use in school. For us, it proves that an immersion school is a good way to help revitalize Indigenous languages and that we do not have to sacrifice our language and culture to build and receive a quality education. This gives us hope the language will continue far into the future.

Igor Xoyon is a professor at Maya Kaqchikel University, where he teaches Maya hieroglyphic writing and Maya math. He has a specialty in bilingual education, with an emphasis in Maya culture, from San Carlos University in Guatemala. He is also the principal of Nimaläj Kaqchikel Amaq’ school.

About the Endangered Languages Project

The Endangered Languages Project is a collaborative online space to share knowledge and stories, explore free learning resources, and build relationships to support Indigenous and endangered language communities around the world. Get in touch at feedback@endangeredlanguages.com.