“I’m guessing it was two in the morning. We threw our sleeping bags out the window to a couple guys standing down there, and off we went in the dark in my sister’s car.”

Christine Mullen Kreamer is deputy director and chief curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. Right now she’s sitting at the small round table in her office, dressed in black, wearing glasses with nearly circular lenses. There’s gray in her bobbed hair. But back in the summer of 1969, she was a seventeen-year-old rising high school senior in Poughkeepsie, New York, who shared an upstairs bedroom with her older sister Annie. The two guys she mentions were her boyfriend and another school friend. They were to meet up with Anna’s boyfriend at the end of the two-hour drive.

“This story begins in misdirection and subterfuge,” she recalls, smiling. “My sister and I left a note on our kitchen table with a bogus address on it and a phone number, knowing my parents would be furious when we returned, but knowing it would be worth it.” The two of them hadn’t planned everything completely, though they came from a family of planners. “We didn’t have picnic baskets full of food. We had a few changes of clothing, and that was it. But we had bought tickets, unlike many people who crashed the gates at Woodstock.”

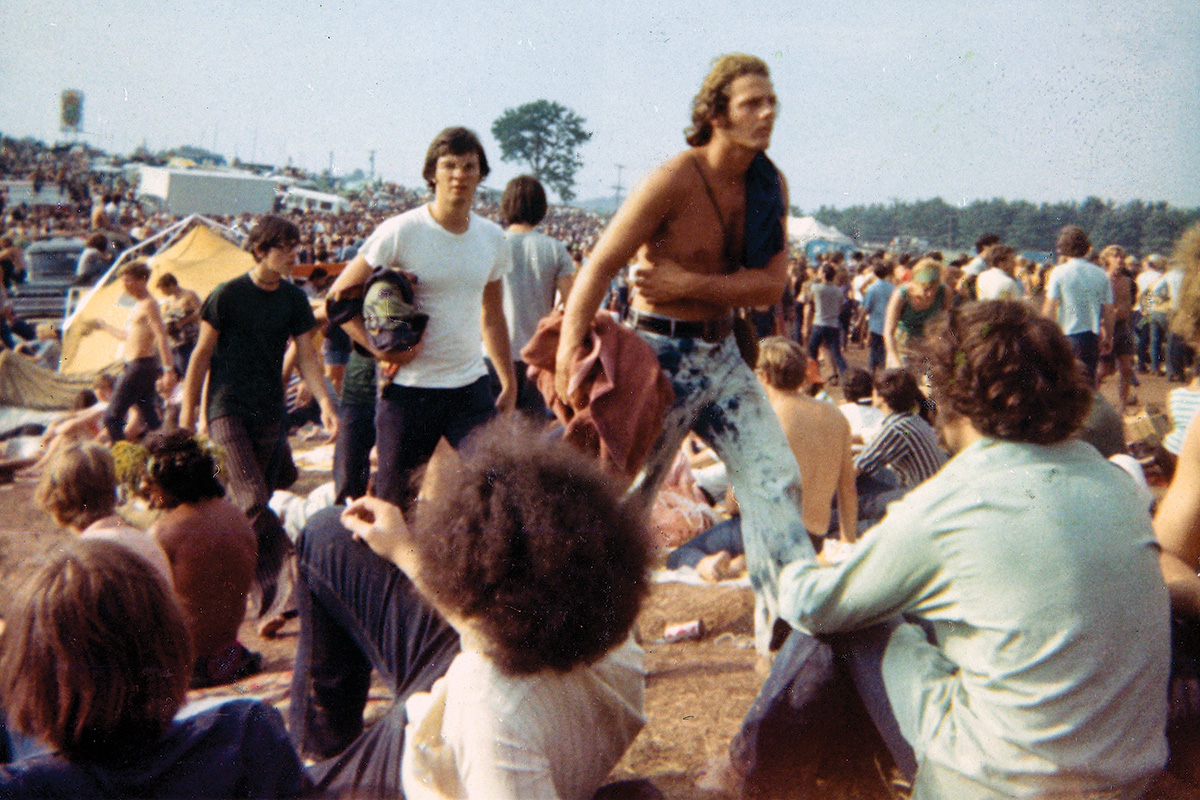

Much is written about the Woodstock Music and Art Fair—about the torrential rains and mud, hallucinogens, free love, and skinny-dipping, but also about tribal amounts of sharing and the marshalling of youthful energy to combat dark societal forces. For some, the festival represents the pinnacle of the Sixties, when a whole segment of society recognized their power and began to come of age.

August 15 2019, marks fifty years since the opening of the original festival billed by promoters as an Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music and held on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm near Bethel, New York. Smaller commemorations are planned, but an official, large-scale anniversary event has been cancelled by Michael Lang, the festival’s original executive producer. Kreamer doesn’t seem to mind. She thinks Lang’s plans were too commercial. The original was different, but it would take a little while for her to discover why.

Neither of the sisters was a hippie. There were acts they wanted to see, groups that the radio stations regularly played. “I didn’t go to concerts, didn’t have much money, didn’t have a car. They didn’t come within walking distance of my home. They were all there, and that was why we had to go!”

Their mom and dad wouldn’t allow it, even though others of their parents’ generation, like the O’Connors down the street, were themselves planning to go. “They didn’t get it. They thought it would be dangerous—who knows what they thought?” But the sisters were determined. “It was going to be what they called ‘a happening,’ and we knew we should be a witness. We weren’t going to be denied this moment.”

What should’ve been a two-hour trip took much longer. “We got caught in a huge traffic jam. People were trying to get there early, and so you just left your car at the side of the road and got out and walked.”

Hundreds of thousands of others would follow the same route, and the traffic stopped cold. Richie Havens’s bass player, Eric Oxendine, trudged fifteen miles only to discover he’d missed their set. The organizers turned to helicopters to get the bands to the stage.

Yasgur’s farm was 600 acres of rolling fields. In one section was a natural depression, a sloping bowl, and a stage had been constructed at the bottom edge. Organizers assured town leaders that they expected no more than 50,000 people. Best estimates of the actual attendance range as high as ten times that.

“It was a magical time,” Kreamer recalls. “There you are: you’re seeing this great expanse of a field, you’re seeing a stage down at one end. We got there early. I was twenty feet from Richie Havens. There he was with his guitar, and people were really mesmerized. The honesty in his voice was a rallying cry to us.”

A helicopter had flown Havens, his percussionist, and guitar player from a Holiday Inn to the site. They had been asked to appear first. Flying over the massive crowd, Havens remembered thinking, “What am I doing here? No, no, not me, not first!”

Today, there is vast disagreement as to how long Havens held the fort—anywhere from one to three hours. He was supposed to go on fifth, but no other acts were near enough to the site, except for Tim Hardin who wouldn’t come out from under the stage. The producers urged Havens to keep playing. He finally played himself off stage for good, the back of his flowing kaftan drenched in sweat, after spontaneously creating an anthemic song he would later record as “Freedom (Motherless Child).” Havens was a high point for Kreamer.

“It seemed like such a vulnerable and courageous act to step out on that stage, start a massive three-day event. As the crowds grew, the gates were pushed down. It wasn’t aggressive at all. People simply wanted to be there.”

In fact, the day before, the concert promoters were forced to make a choice. The stage wasn’t finished yet, and neither was adequate fencing. Only one of the two projects could be completed. They made the only decision possible: the musicians came first. Woodstock would become a free festival.

“By the end you couldn’t get anywhere near the stage. It was a sea of people. You actually had no sense of the numbers. But you were part of something larger.”

The sisters needed a home base, and they chose to pitch their tent under some distant trees. “We needed to find each other. My old boyfriend—he’s an artist living in San Francisco now—he roamed around a lot more than me. But this was the era before cellphones.”

The next afternoon, they sat under the trees, “probably recovering from near heatstroke. I’m of Irish decent, so I burn.” They could hear the songs but were unable to see the stage. That’s where she first heard the Latin rock band Santana. It might be true that most of the crowd was in the same boat. Santana was a phenomenon in the San Francisco Bay Area but had yet to record an album.

“I said to myself, this is a really cool sound.” The sound of the congas were new to her. “And then I went out of the shade and into the sun to see what they were about. Good God, the crowd had really grown!”

Kreamer was a huge fan of Jefferson Airplane, whose songs “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit” had soared up the charts that summer. The band had been scheduled to appear as the sun was rising, but they may have started a bit after that. Kreamer remembers it the way she remembers it. “It feels like it was about five in the morning, and Grace Slick just came up to the microphone. ‘Morning, people!’ in that great Grace Slick voice. It was, I think, after torrential rains. That was how I woke up.”

There were performances scheduled through the day and night, but Kreamer’s plan was never to stay up the whole time to see everything. She only knew that she wanted to experience things that pulled her out of her comfort zone. “My own experience of Woodstock was one of grabbing onto an uncertain moment and embracing it because it felt right to feel part of something bigger. You don’t know what role you’ll play, but you know you’ll be a player.” She grew up in a family that wasn’t connected to the arts or to culture, other than their Irish American heritage and sports.

Her mental scrapbook is varied. She remembers the good times spent with friends, beading love beads because the hippies were doing it, picking her way through the crowd, watching people hanging from the speaker towers (one of whom later passed out and landed on her), and seeing the skinny-dippers in the pond.

“I don’t recall a thing about what we ate or drank over the three days. There didn’t seem to be a good plan, but there was a spirit of sharing, as well as vendors for a short while, but it wasn’t about making money. It was about getting services to people. There were public service announcements: ‘don’t take the brown acid!’ There was medical care onsite and a baby born and announced.”

The consistent flow of helicopters made her nervous. “Seeing those, you made a mental shift to the Vietnam War. All the positive things we were experiencing were deeply connected to an opposition to the war. I had protested as a high school student. Those helicopters connected me to what we saw every night on the news. That informed the Woodstock moment too.”

“People had come to celebrate music that had a message. It was a time of great promise: peace, rebellion, civil rights, love, enhancing the social safety net, anti-litter campaigns, caring for your brother, even your global neighbors, all of these. So many of the bands were saying these things, and with experimentation. I mean, acid rock—it’s called that for a reason. It was a moment where experimentation was social, but it was also chemical. That was part of the vibe.”

The sisters were aware of the drug culture and what was judged fairly safe, though this was a highly individual decision. “It was part of that generation. There were various ways to enter into a higher consciousness. Grass was circulating. Chemicals were circulating. So were wine, beer, and food, and you had to decide whether you wanted to take part. You had to decide, and you trusted your peers. Being young, I was not going to veer off into some truly unknown dimension. No one judged unless you were being rude or were whacked out on drugs, and most often those people were guided to the medical tent. We never worried when we fell asleep except that it might rain again. I think people saw me as a little clueless, and now that I think about it, that they were protective toward me and made sure I was with my people. I felt that people came to Woodstock with the best of intentions.”

“There is the old joke, ‘if you remember Woodstock, then you probably weren’t there.’ Sliding in the mud? I was more a watcher as I had limited changes of clothes. I also wasn’t going to take off all my clothes and jump in the water. I wasn’t that free a person. For me it was about the music.”

With all the rain, the schedule had been pushed into Monday. Jimi Hendrix closed the festival with a blistering set that began at 9 a.m. “Hendrix transcended race, and everyone loved his music. Hendrix was a vet, and so his performance of ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ took on greater poignancy as a painful, courageous statement about both loving and serving one’s country without agreeing with the current policies about the war.” She stops herself, suddenly unsure. “When did Hendrix play? Not a hundred percent sure, but it must have been at night?”

Going home after the concert to face her parents was as tricky as you might imagine. “Funny how things change from three days of peace, love, and music to seeing the stern faces of our parents and we realize our cover was blown.” Her father told her sister, Annie, that they were disappointed in her, but they told Christine that, actually, they expected something like that from her. She took this as a point of pride.

“We did get grounded for, I guess, a month, but we weren’t worried. We had ways of moving beyond the bounds of the household as we saw fit. Both my parents have joined the ancestors, sadly, but they just didn’t get it.”

Fifty years on, far away from that seventeen-year-old girl, she ponders Woodstock’s meaning. “Thinking about my senior year, I did see myself moving away.” She stopped hanging out with friends who weren’t tuned into social issues. Now she saw them as a little shallow. She added “granny glasses” and big hair to her bell bottoms and army jackets. She took some time off after high school to travel Europe with the guy from the Woodstock trip who had not been her boyfriend but now was. “Our experience of Woodstock had brought us together.”

“It was the Sixties after all,” she quips.

She thought deeply about her next moves and determined they were not connected to a career or money. “It was really about culture and experiences, and maybe that was another part of the Sixties generation. We weren’t overly practical, and it was really about enhancing who you were as a person and discovering how you fit into the broader scheme of things.” She sloughed off the Mullen family pragmatism and went into art history, her sister into psychology.

The world seemed much more global after Woodstock. “We were the generation to make a difference. You went into activism, politics, or law. A college professor could make a difference. Students fought for the implementation of ethnic studies programs.” Kreamer pauses for a moment, thinking over things. “Now at the National Museum of African Art, my work is focused on telling stories through objects. Maybe the fact that these foundational moments like Woodstock inspired so many stories and ways of telling means that I carry some of that with me, that it opened me up to a much wider world of connections and experiences.”

“Part of the promise of that generation and one I really hope the young generation today picks up on: this is your world. You’re inheriting it, and it’s a bit of a mess in many ways. This is a time to think of the greater good, think beyond the individual, think about how we can make a difference collectively. That, for me, was the Sixties. It was the spirit of Woodstock in so many ways.”

Kreamer smiles.

“So maybe Woodstock did have a role in my future, but I sure had a good time.”

“The secret message communicated to most young people today by the society around them is that they are not needed, that the society will run itself quite nicely until they—at some distant point in the future—will take over the reign. For society to attempt to solve its desperate problems without the full participation of even very young people is imbecile.”

—Alvin Toffler, writer, futurist

Charlie Weber is the media director at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.