My grandmother always loved a lunch special—especially with good company. But she was willing to pay full price at Russ & Daughters Cafe in the Lower East Side. Somewhere along the way, what was once the humble food of Jewish immigrants—herring, lox, whitefish—became a special, celebratory food. Whenever we went, she always discussed the prices: expensive, but worth it. But there was one exception. She couldn’t bear to pay deluxe prices for a knish, the simple food which her family had sold for five cents apiece when she was a child.

For me, these foods were always the foods of a special occasion. In that sense, they were not too different from my grandmother’s signature breakfast offering, “Smile Toast.” She had a little yellow press which left the indentation of a big smiley face on a piece of bread which she toasted, buttered, and covered with cinnamon sugar. This was a special treat for mornings after a sleepover at her apartment.

While Smile Toast is an iconic food of my own childhood, the cuisine we ate at Russ & Daughters is part of a larger shared cultural past. There’s something special and ineffable about that, a sense of belonging and pride. Though we also always loved getting Chinese food as a family, the fish at Russ & Daughters was our food. And in a tangible sense, my grandmother was my connection to the lost Jewish immigrant world that it came from, a world that in myriad ways subtly shaped our family’s culture.

I wanted to document this connection and to explore it in my music. Before my grandmother passed away, I asked her to tell me some of her favorite stories of her childhood so that I could record them and use them as the basis for a new song cycle.

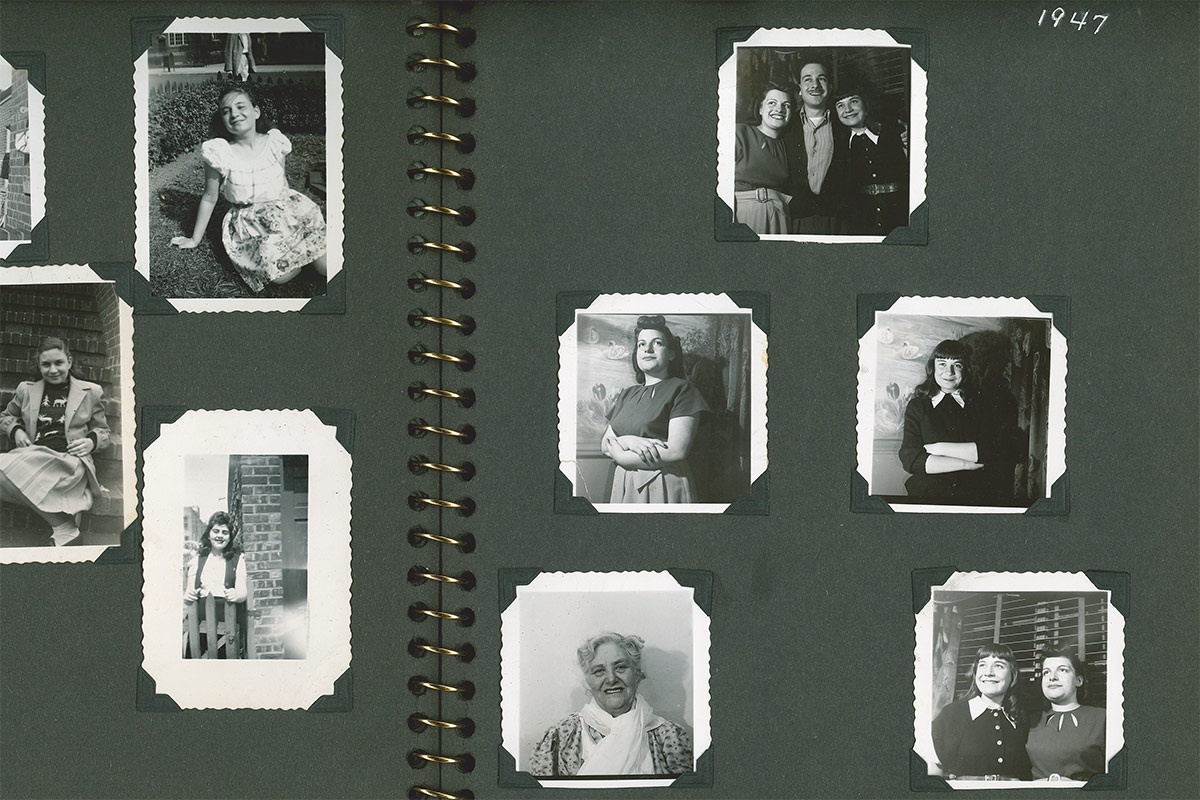

She was the youngest of three children, and I understood that when she died, all that would remain of her childhood memories would be faded black-and-white photos. Reflecting on her youth, she was filled with gratitude. She would say that she was lucky and had a very good childhood, but she didn’t think her stories were anything special. And yet, if I didn’t record them, our family’s knowledge of its own past, our sense of being rooted in our culture, would be forever weaker.

My grandmother, Irene Weiser, was born in New Jersey in 1933. Her parents had come to the United States from a town near Kyiv in the 1910s. While she was raised speaking English, her parents were always more comfortable in Yiddish. She told me about her childhood summers in Coney Island, her trips to the Russian bath, going to the mountains with her Aunt Fanny, and tagging along for her mother’s corset fittings. Though in a sense these topics are mundane, they are emblematic of storied episodes of Jewish American immigrant life and show how our family’s story is embedded in a broader cultural history. They were also the very fabric of the day-to-day life of her childhood, and she was happy to reminisce about them.

One of the topics she touched on was her family’s knish store—Litwin’s Famous Kosher Knishes—known to me through family lore and a handful of pictures in which their storefront advertised its five-cent knishes. “My uncle Joe stood by the oil,” she explained. “When we came over to get the knishes, he said in Jewish, avek! Avek! [Away!] He was so nervous that I’d get hurt.”

The family jokes that Yonah Schimmel’s Knish—a famous establishment still operating on Houston Street in Manhattan—drove them out of business. I don’t know what really made them decide to close shop, but I love the way the details of her story bring color and life to those faded photos: little children helping out at the store near dangerously hot oil for frying the knishes and a nervous uncle hovering nearby. And I love that she called Yiddish “Jewish.” That is precisely what “Yiddish” means, and yet this definition of “Jewish” typically can’t be found in the dictionary.

I was compelled to make these recordings in no small part because of what I have learned working at the YIVO Institute since 2016. YIVO—a library, archive, and research center of Jewish history and culture—has always privileged the study of folklore, language, and the intimate everyday stories of individuals over the monumental, sweeping stories of politicians and nations playing on the world’s stage. Collecting the seemingly insignificant stories of people like my grandmother was YIVO’s raison d’être.

For example, in 1942, YIVO solicited entries for an autobiography contest responding to the prompt: “Why I Left the Old Country and What I Have Accomplished in America.” This contest was created to allow YIVO to study Jewish life while strengthening the communal sense of historical continuity across the rupture created by mass immigration. The contest came from YIVO’s new headquarters in New York City; the institute had moved in 1940 for the prospect of a better future when its original Eastern European headquarters faced Soviet occupation and soon thereafter suffered German invasion.

“It’s hard to find a bigger upheaval in all of Jewish history than the mass immigration to America of the last 60-70 years,” the contest notice explained in Yiddish. Though Jewish historians have written about this epoch, the notice continues, the stories of “the great mass of immigrants, who themselves sacrificed and with their own hands built their lives and their community institutions in the new land—they have not been sufficiently recorded.”

YIVO wanted historians to be able to write the history of Jewish immigration through the stories of ordinary people. They took great care to note that this contest was for all Jewish immigrants who had made their home in the United States and Canada regardless of their gender, level of education, socioeconomic status, or political affiliation. While many institutions focus on documenting influential organizations and prestigious individuals, YIVO’s motto had always been “from the folk, for the folk, and with the folk,” so they gave forward-looking attention to groups who might otherwise be overlooked. All they asked was that the responses be detailed, to the point, and truthful. “Don’t think that ‘kleynikaytn’ [trivialities] are not important. On the contrary, it is generalizing deliberations on the ‘difficult situation’ and about ‘dire straits’ which are of meager value.”

It was the very details that might be brushed off as kleynikaytn—the kind that I cherish in my grandmother’s account of her childhood—that YIVO was interested in. Having absorbed this ethos at YIVO, I was emboldened to do something with my grandmother’s stories.

After recording my grandmother, I transcribed the tape and loosely edited and rearranged some of our conversation to form song texts. Reading her words over and over again with the close care that is necessary for setting them as songs, I saw how much poetry there is in plain speech. The simple but poignant lines she used to launch into her story are a beautiful example:

“I was very young. We used to go to the beach ourselves. We ran in the water. We came out. We were there all day. There was no limit.”

Each of these short sentences could be expanded and elaborated on, and yet it is so evocative how they naturally came out. This kind of organic simplicity is something I deeply value in music but is very hard to achieve.

Similarly, I was struck by how much depth one could read into each detail she shared. Their summer living quarters and the special privileges afforded to her older brother Morty are a moving example:

“We had a room in the back of the store. They had one bathroom. Just a toilet. Maybe a sink, no bathtub. All of us slept in one room, except Morty. There was a hotel attached to the store. For Morty they gave him a tiny room, but for us we all slept in one room.”

Working on these songs after she passed away, I was also struck by how similar my grandmother and I are. I hear echoes of our relationship in her love for her mother and her Aunt Fanny. Describing Fanny, she said:

“…and when she saw me she used to jump up and down, she loved me so much. I loved her. My mother was a little jealous. But you know I loved my mother. Nobody could love their mother more than I loved her.”

When I was a child, my grandmother used to visit frequently to take care of me. Years later, she often recalled that I always greeted her by jumping with joy.

After transcribing the recording of my grandmother, choosing which episodes to tell flowed naturally out of the stories that she had focused on. Capturing the elegant simplicity of her plain-spoken speech and trying to get the tone of each story just right, on the other hand, was a big challenge. As I set my grandmother’s words to music, I was careful to try to capture her tone and the rhythms of her speech in the score. I wanted to showcase the wonderful specificity of the way she spoke, including all of her hesitations and asides.

Together, the seven resulting songs form a song cycle that I titled Coney Island Days, which became the second half of my latest album, in a dark blue night. (The first half of the album sets to music Yiddish poetry about New York City at night by poets who came to the city around the same time as my grandmother’s parents.)

When I hear these songs now, I’m brought right back to my grandmother’s dining room table. I’m so glad to have put these stories in a form that preserves them and makes them easy to share.

In the liner notes for in a dark blue night, Niki Russ Federman, the fourth-generation co-owner of Russ & Daughters, commented that “there was very often a feeling among the immigrant population that their own stories were not that important. It wasn’t shame, exactly, but the idea that their family history wasn’t interesting.”

Niki’s remarks speak to exactly what I think YIVO was hoping to do for Jewish immigrants in 1942: not just to record the details of their experiences for the historical record but to show the world, and to show the immigrants themselves, that their lives mattered, that their hard work and aspirations, tragedies and joys were a part of the beautiful, sweeping story of Jewish history and of the American immigrant experience.

I closed Coney Island Days with my grandmother’s reflections on memorializing her parents in a monument on Ellis Island. She and her sister Bea paid to have their parents’ names listed on The American Immigrant Wall of Honor, and, at the end of her life, she felt guilty for not also doing it for her beloved Aunt Fanny. Though she may not have used YIVO’s vocabulary and framework, she was nonetheless concerned with how history would remember her and her family’s contributions.

If my grandmother could hear my songs, I hope that they might help her appreciate the kleynikaytn, the small, personal, and seemingly insignificant moments of her childhood, in a deeper way. I like to think that maybe she would be proud—not of me, but of the part that she and her family played in the story of the United States.

Alex Weiser is the director of public programs at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the composer of and all the days were purple, an album of songs in Yiddish and English which was named a 2020 Pulitzer Prize Finalist for Music.

For nearly a century, YIVO has pioneered new forms of Jewish scholarship, research, education, and cultural expression. The YIVO Archives contains more than 23 million original items and YIVO’s Library has over 400,000 volumes—the single largest resource for such study in the world.