This year marks the sixtieth year of existence of Mariachi Los Camperos, and more than five since the death of the group’s founder and former musical director, Natividad Cano. So it was particularly meaningful for his protégé, Jesús “Chuy” Guzmán, to find himself sitting with his musical campañeros on GRAMMY night awaiting the results. And then they came.

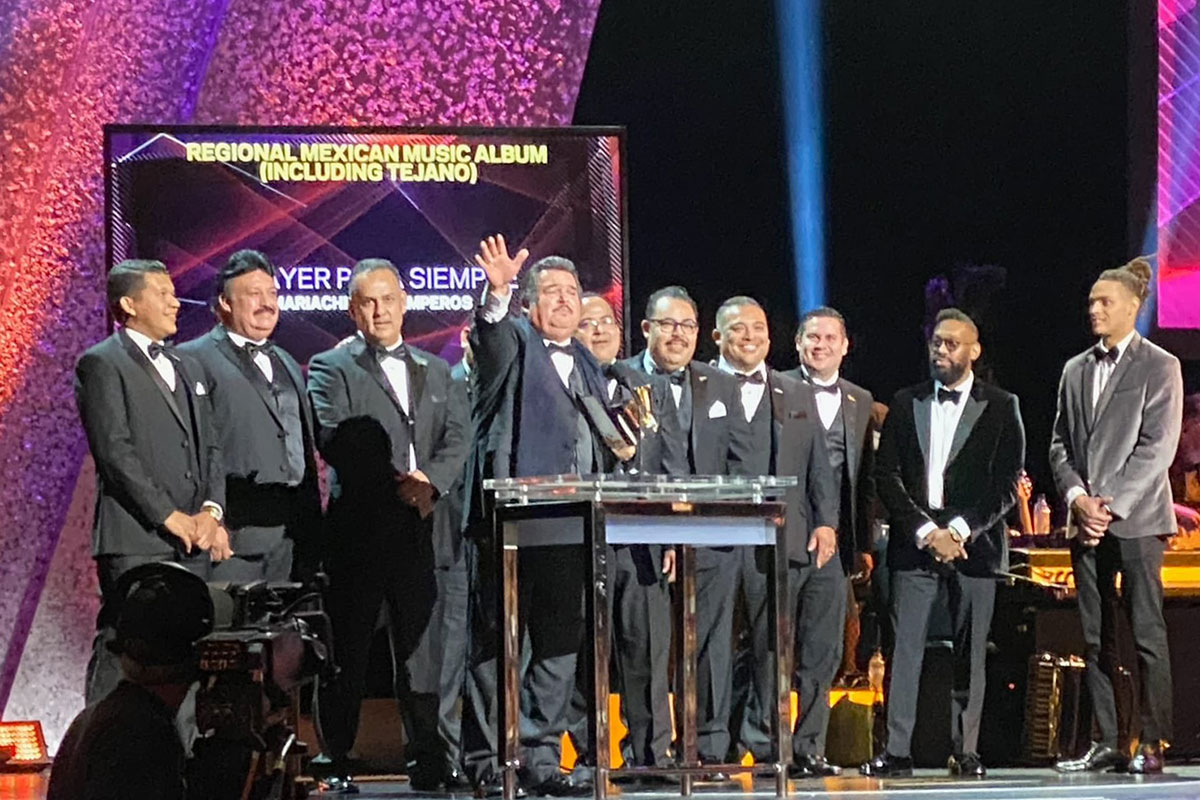

“And the GRAMMY goes to… Mariachi Los Camperos, De Ayer para Siempre!”

Cue the cheers and the musicians half-trotting to the stage, where Guzmán offered words of appreciation as he raised the award engraved with the group’s name and the category of Best Mexican Regional Album.

Beyond that concert hall, many others would cheer the recognition. The time-honored group represents much more than music. Since the mid-twentieth century, the sounds of the mariachi have taken on broader significance in the social and cultural world it inhabits. Leading musicians have long battled demeaning stereotypes that paint the music as artistically inferior, barroom busking, and shallow stereotype.

Cano was one of those leaders who spent his life fighting for respect—musical, cultural, and social. He faced multiple forms of discrimination in his life as a musician. In his native Mexico, he suffered the derision of classically trained musicians who saw his beloved tradition as unworthy of “serious” appreciation. In the 1960s, he faced racial discrimination in the United States; on one occasion, he was not allowed in a restaurant while on tour in Texas. Deeply wounded by this treatment, he saw in his music a path to social and cultural justice and equity for his Mexican heritage.

As Los Camperos launched their sixty-year career in the 1960s, and as visionary musicians strove for greater musical respect, societal events boosted the music’s prominence. The sound and image of the mariachi took on new meaning as a cultural icon of the Chicano civil rights movement. Demonstrations against social and racial injustice and cultural events declaring pride in Mexican heritage embraced mariachi music as a forward-looking symbol of identity.

Cano went on to create the first mariachi dinner theater, La Fonda de Los Camperos on Los Angeles’ upscale Wilshire Boulevard. La Fonda catered to, in Cano’s words, “todos colores y sabores” (all colors and flavors) of people. There, the music came first, framed by the inviting surroundings of the family-friendly restaurant. Cano insisted on the highest caliber of performance and stage presence from his musicians and an atmosphere of dignity and respect for his music and culture.

Personal and social dignity were his watchwords, as he sought the most prestigious concert halls for his group, performing at such venues as the Kennedy Center, the Los Angeles Music Center and Disney Concert Hall, and New York City’s Lincoln Center. In 2006, Cano’s Smithsonian Folkways album ¡Llegaron Los Camperos! Concert Favorites became the first mariachi-centered album nominated for a GRAMMY, and in 2009, Amor, Dolor y Lágrimas: Música Ranchera earned the coveted award. They also contributed to the GRAMMY-lauded children’s album cELLAbration: A Tribute to Ella Jenkins.

The “people power” that fueled the Chicano movement carried over into public school programs as well. School mariachi programs were launched first in California, Texas, and Arizona and quickly spread throughout the Southwest and Mexican American communities in cities such as Chicago and New York. Today, hundreds of school programs at the middle school, high school, and collegiate levels teach mariachi music as part of the curriculum or as adjunct student enrichment activities. Educators such as New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza—who at the beginning of his career taught mariachi music in Tucson’s Pueblo High School—proudly point to the striking improvement in academic performance by students enrolled in mariachi programs.

This American social setting also pushed the tradition to be ever more inclusive and equitable. The even playing field offered by schools and community-based learning programs broadened gender equality in the tradition. In these learning programs, the number of girls roughly equaled the number of boys. In the 1970s, pioneering women instrumentalists broke the longstanding gender barrier of the male-dominated professional mariachi world, followed by high-profile, all-female ensembles such as Mariachi Reyna de Los Angeles who came to the fore in major concert venues. Even LGBTQ advocates have embraced the music as forwarding their cause of social justice. Mariachi Arcoiris de Los Ángeles proudly represents itself as the first openly gay mariachi ensemble.

Winning a GRAMMY is indeed special for the artists receiving them. But in the case of mariachi music, the glow travels far beyond the ceremony, spotlighting many other agendas that culminate in a greater respect for Mexican cultural heritage. A moment to celebrate? Yes, indeed, for so many people and for so many reasons.

Daniel Sheehy is director and curator emeritus of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. He is also a co-founding musician in Mariachi Los Amigos, the longest existing mariachi ensemble in the Washington, D.C., area.