The Power of Oratory

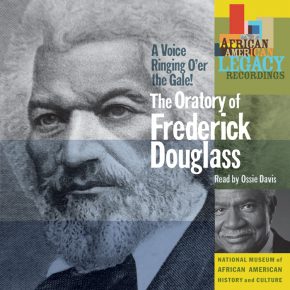

The power of words in African American culture is the power to affect the heart and head, ideas and ideals, to disclose the truth, to change lives. This phrase also refers to the power to influence others, either for good or evil, through language. The impact of strong oratory on American history is well documented. Some examples that come readily to mind include George Washington’s Farewell Address, Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is Fourth of July?,” Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, or Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony before the Credentials Committee at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Because of the early limitations on their communication with one another, the concept of freedom of speech holds a special meaning for Americans of African descent. These Americans place a high value on effective speaking and rhetoric. Traditionally, the most eloquent speakers garner influence, respect, and admiration. Some, such as activist-comedian Dick Gregory and educator-comedian Bill Cosby, rely primarily on wit and economical verbal devices; others, among them museum director Johnnetta Betsch Cole and the late U.S. Representative Barbara Jordan, look to elevated diction and elaborate grammar. Whether speakers employ a less formal or a more structured approach, they often find inspiration or source material in oral expressions from the past, including spirituals, gospel, blues, and work songs.

Some of the first African American voices to gain the attention of whites were orators who could speak powerfully of the experience of being enslaved, such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. Others included abolitionist figures such as Henry Highland Garnet, who in his famous 1843 “Address to the Slaves of America,” exhorted enslaved blacks to strike for their own freedom. “Rather die free men than live to be slaves,” he pronounced.

Several generations later, in response to the post-World War I race riots of 1919, the poet Claude McKay expressed a similar view in his poem, “If We Must Die”: “Like men we’ll face the murderous cowardly pack,/ pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” Although the poem appeared in written form, its rhythm and rhyming beg for recitation aloud. During World War II, Winston Churchill uttered these now famous lines over the radio airwaves to rally the British during the blitzkrieg. These eloquent calls for resistance represent the often-expressed sentiments of blacks throughout their long struggle against repression and discrimination.

The 1920s and ’30s brought a new, more literary voice to the desires, needs, and aspirations of black folk. The Harlem Renaissance flourished at that time, bringing to prominence African American intellectuals and writers with a keen ear for the voice of the folk, such as Sterling Brown, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston. In addition to the work of such distinguished literary figures, poetry in the form of the blues, gospel, ballads, and sermons revealed characteristics of black expression. Also in the 1930s, other common folk had their say when the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Federal Writers’ Project recorded the oral testimonies of ex-slaves. These personal stories provided firsthand accounts of the experience of slavery and valuable examples of vernacular black expression.

“Sounds of the Civil Rights Movement,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

In every epoch of American history, black voices not only have called for resistance, but also have spoken constructively to reaffirm the nation’s principles and to hold America accountable for the fulfillment of its core democratic values of freedom and equality. The calls for deliverance from the bonds of slavery later became the language used to demand civil, labor, women’s, gay, and disability rights, as well as political, social, and cultural change. During the height of the modern civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr., in his 1963 speech “I Have a Dream,” gave eloquent expression to the idea of equal rights for all Americans:

When we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!”

“We Shall Overcome,” the anthem of the movement led by King, became and remains the mantra for numerous social justice causes that have followed.

Storytelling

Rex Ellis, of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, is a great storyteller himself and a member of the National Association of Black Storytellers. He likes to emphasize the storyteller’s particular power to communicate and provide common ground:

[It is] the stock in trade of the spoken word … and the tellers who bring the words to life … who understand the essence and meaning of the words that have the power to inform, interpret, represent, transform, and empower the listener. Storytelling is a universal art that teaches norms, customs, and perspectives about a community and its culture.

The oral tale, as contrasted with a written text, is usually improvisational and to some degree communal—performed interactively, in dialogue with an audience. While storytelling is distinctive, it shares similarities with the art of oral poetry.

In recent years, storytelling has found new forms of expression in music videos and in the many interactive platforms of the Internet. At these online sites the doors are open to shared stories and experiences. A private incident or local performance can become a touchstone for millions.

Storyteller Victoria Burnett gives a lesson in BBC (Black Baptist Church) 101 at the 2009 Folklife Festival. Video by Charlie Weber

Notable also is the way in which storytelling has evolved within the African American deaf community. Their signs, gestures, and body language represent art as well as communication. One need only experience the signer who performs with Sweet Honey in the Rock to recognize this distinctive mode of black expression. Like other black communities, deaf African Americans were segregated for decades from the larger deaf population and evolved independently. As a result, black sign-language users developed their own distinctive gestures, and a general preference for using more two-handed signs than is common amongst the broader group.

Poetry

Young poets during the second half of the twentieth century were inspired and nourished by earlier generations of black poets, including such renowned figures as Phillis Wheatley, Paul Laurence Dunbar, James Weldon Johnson, and Langston Hughes. But these later artists felt the need for a new genre of poetry that would suit their activist approach to the world.

They developed a more assertive, confrontational style of writing and delivery that allowed figures such as Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, Haki Madhubuti, E. Ethelbert Miller, and Sonia Sanchez to play an important role in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Through performers such as Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets, this new black poetry influenced early street rap poetry and rap music, which in turn nurtured the hip-hop and spoken word movements among a younger wave of artists.

Building on the past, the new black poetry functions on a sacred-secular continuum. It favors a pronounced rhythmic pattern and uses the Black idiom—including rap, call-and-response, and signification.

Spoken Word

Classified sometimes as poetry and sometimes as hip-hop, spoken word is a literary art form in which the lyrics or words are spoken, not sung. Spoken-word events are presented occasionally as performance poetry set against a musical background with a percussive beat. In African American spoken word, those artists whose backgrounds include more formal literary training (and who generally are older and defined as poets) are distinct from the younger, more contemporary practitioners who may come from an educated background or the subcultures of hip-hop, rap, or the street. As a result, the realm of spoken word has seen an evolution of the form and an expanded range of practitioners across several generations.

Since the mid-1980s, one popular venue for observing spoken word in action is the “poetry slam,” a competitive art form that combines poetry and performance. Events sanctioned by Poetry Slam, Inc., and those organized by Russell Simmons’s Def Poetry Jam, take place across the United States. Tanya Matthews, an active spoken-word artist based in Cincinnati, suggests that in such venues spoken word can be evaluated by the way in which the words are rhymed to a rhythm, by the back beat, by its musical accompaniment, and by whether it is an oral or written composition.

Read “Say It Loud: African American Spoken Word” from Smithsonian Folkways

Oral Histories

Walt Whitman, one of America’s great poets, observed in 1855 that “the genius of the United States is not best or most in its executive or legislatures, nor in its ambassadors or authors or colleges or churches or parlors, nor even in its newspapers or inventors—but always most in the common people.” In the case of African Americans, oral sources—coming directly from “common people”—offer new, illuminating perspectives and insights to inform American history.

And in the case of the 1930s WPA recordings of former slaves, oral testimonies and personal narratives provide fertile material for cultural historians who seek not only the content of these testimonies, but also their manner of verbal expression. Similar benefits came from the narrative use of oral history in Alex Haley’s book, Roots, as well as the hundreds of interviews of African Americans collected recently through StoryCorps’ Griot project done in collaboration with the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Oral histories may supply important information on a variety of practices—including agricultural methods and foodways, clothing styles and adornment, and tangible places such as one’s home, neighborhood, school, sanctuary, street, or street corner. Exposure to such firsthand accounts can evoke personal memories and help others to recall their own favorite tales and stories.

Read the Smithsonian Folklife and Oral History Interviewing Guide

Conclusion

The National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival have demonstrated their commitment to documenting and preserving the oral expressions of a people whose voices were muzzled, who were denied the opportunity to read and to write, and whose speeches and oratory often did not survive.

A people’s culture is inexorably linked to its language, and by helping to raise public awareness of African American linguistic creativity, the museum highlights a major aspect of black culture. In the process, the museum moves closer to its goals of helping all Americans to learn more about African American history and culture, and to understand and appreciate how this history and culture provide a powerful lens for understanding what it truly means to be an American.

James Alexander Robinson was the curator for Giving Voice: The Power of Words in African American Culture at the 2009 Smithsonian Folklife Festival. He is a doctoral candidate in interdisciplinary black studies at the University of Iowa.