For as long as they have lived in the country’s highlands, Armenians have harvested the indigenous edible green plants, transforming them into cherished dishes. The high mineral content of Armenia’s soil, made possible by centuries of volcanic ash, makes the country a botanist’s dream. Thus, while some may take offense at the old Russian proverb, “What are weeds for Russians is food for Armenians,” there is some truth in the saying.

Every year, locals pick countless plant species from the mountains and hillsides. Novel to foreign tongues—both in pronunciation and palate—many of them form the backbone of signature traditional recipes.

Yet for those looking to learn more about these edible plants, a simple Google search will not suffice. Save for a few efforts to preserve Armenian foodways, like The Thousand Leaf Project, the only way to access these foods in their authentic form is by traveling to the depths of the countrysides and meeting those who carry the burden of the nation’s culinary heritage: Armenian grandmothers.

Greta Grigoryan is your quintessential Armenian tatik. She lives in Yeghegnadzor, a quaint town in Vayots Dzor province two hours south of Yerevan, the capital city. For centuries, Yeghegnadzor and its surrounding regions have been the site of many hardships, from invasions by neighboring empires to famines and countless earthquakes that have reshaped the region’s arid, hilly terrain, giving the region the name “Gorge of Woes.” Despite the harsh history of this land, its people are miraculously resilient, a trait which is often expressed through food.

Greta expertly maneuvered her small, Soviet-era kitchen preparing surj (Armenian-style coffee), doling out old wives’ tales and food preferences of her family members. With swift motions, her agile hands darted from tabletop to countertop, chopping, measuring, and pouring ingredients. She used the most basic elements—onions, walnuts, garlic, and lots and lots of oil—making way for the star of this meal: aveluk.

Aveluk is a wild sorrel specific to certain regions of Armenia. It is renowned for its medicinal properties and unique taste, reminiscent of the grassy fields from which it is harvested. Each spring, villagers trek to these fields to harvest its leaves—sometimes alone, sometimes in groups, depending on whether they are feeding their families or selling in the shookahs (markets). After harvest, the leaves are often hung to dry and used year round—sometimes lasting up to four years, according to Greta.

In its dried form, aveluk is almost always braided into long, green plaits. The method of braiding is itself a tradition, typically performed by women sitting outdoors if the weather is nice or in the shade of their patio, chatting, and passing the time. The length of braided aveluk must equal four times the height of the person braiding it. “Because families were so big,” Greta said, “we have to weave long braids to make sure we can feed everybody.”

“All these plants and weeds have fed the families of this region, even in times when food was scarce,” Greta explained. “And now, everybody loves these dishes—the poor as well as the rich.”

But it wasn’t always that way, she recalled. Her grandmother, for example, advised against certain plants. “She used to say that even donkeys won’t eat sheb [wild sorrel variety]. I asked her, ‘Well, Tatik, what then should I eat?’ And she would reply, ‘Aveluk, my dear. You should eat aveluk.”

Her grandmother’s advice did not seem to affect Greta’s affinity for even the most obscure greens. She rattled off plant names—spitakabanjar, mandik, loshtak, pipert—insisting each be written down and given fair recognition, even venturing deep into storage to retrieve various dried greens, explaining each plant’s story and personal significance.

These recipes are hereditary, she explained, passed down from grandmother to mother, mother to daughter. Sons are excluded from this transmission, as gender roles are fairly strict in traditional Armenian households. Men’s cooking duties are often limited to preparing meat and working in the field.

Student filmmakers at TUMO Center for Creative Technologies in Yerevan produced this short documentary about Greta Grigoryan and Lusik Mkrtchyan, in collaboration with the Smithsonian and My Armenia.

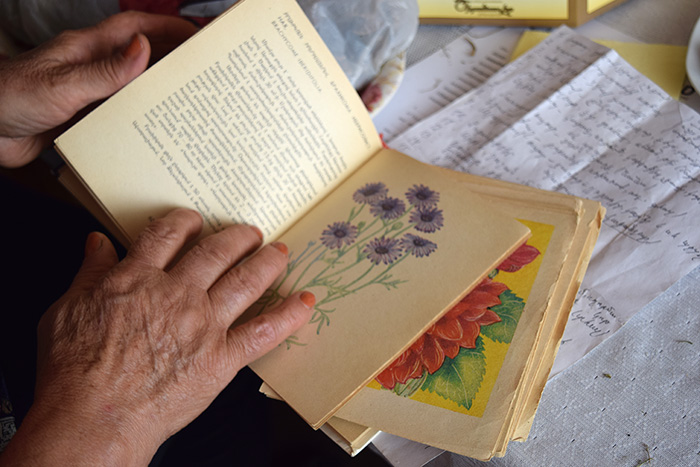

As she leafed through her Soviet Armenian encyclopedia of wild plants, Greta remembered that from a young age she harbored a great love for the abundant leafy greens. “I liked to taste all the grasses in my garden. I was curious about it, more so than other girls my age.”

Today she maintains her own garden, growing vegetables from local seeds—a rare phenomenon these days, as most Armenian farmers opt to use foreign seeds. Local varieties, unfortunately, do not yield large harvests—only enough to feed one family.

Despite the regional and social significance, these greens are not universally loved, even among Armenians. The taste is so closely intertwined with the fields that it is off-putting for some. There is also the confusion over Western Armenian food versus Eastern Armenian food, a result of the dispersion of Armenians from the former Ottoman Empire at the turn of the twentieth century. Aveluk is about as Eastern Armenian as it gets.

Armenia’s national cuisine is so diverse, in fact, that what may be considered a traditional dish abroad may not be commonly eaten in Armenia. Arianée Karakashian, a Canadian-Lebanese Armenian, recently made her first trip to her ancestral homeland and reflected on her expectations versus the reality of Armenian food.

“Here in Yerevan, it’s the Syrian restaurants that remind me of my mother’s cooking back in Canada,” she said. “Coming from an ethnically Armenian family, you would expect the Armenian food your mom makes to taste similar to the Armenian food an actual mom in Armenia makes, but it is so completely different. For now, I’m trying to expand my taste bud knowledge. You discover new things about what you thought would be self-evident, but that’s the point of growth.”

This is perhaps why many restaurants in Yerevan prefer to play it safe and, outside of the occasional item, not offer these traditional dishes. One exception is Dolmama, a quaint, cosmopolitan restaurant on Pushkin Street that has carved itself a niche for offering traditional dishes of both Eastern and Western Armenia with an elegant spin. The menu includes signature soups made from aveluk and pipert, both of which have become extremely popular items for their novelty and taste.

Omitting these signature plants from the menus of restaurants in tourist areas highlights an interesting dilemma. On one hand, many of these dishes remain preserved in their authentic contexts, to be experienced in the regions in which they originated (as long as you know where to find them).

But that means most travelers in Armenia are missing out on the flavors and generations-old practices that reveal so much of the nation’s identity. And if they’re missing out on that, what are they being served instead?

So, while it can be difficult to find many of Greta’s beloved vegetables outside of her kitchen, it may be that there is simply no demand yet. Tourists don’t know to expect these dishes upon arriving to Armenia, and the locals who love them need look no further than their own kitchens. For no matter how many restaurants offer aveluk on their menu, if you ask a local how they like it prepared best, they will always say the same thing: “The way my grandmother made it.”

Karine Vann is a writer based in Yerevan and originally from the D.C. area. She is the communications manager for My Armenia, a program developing cultural heritage in Armenia through community-based tourism.

Sources

Petrosian, Irina, and David Underwood. Armenian Food: Fact, Fiction & Folklore. Bloomington, IN: Yerkir, 2006.

Gabrielyan, M., Melqumyan, H., Mkrtchyan, S., and Tsaturyan, R. Armenianness Every Day: From above to below… Yerevan, Armenia, 2015.