Stare long enough at a show poster, and it becomes a crystal ball. Will you be surrounded by the fresh-off-work khaki crowd? Teenagers out for a night in the pit? Carhartt or cowboy boots? How much will you regret forgetting your earplugs?

Covering the light posts and bulletin boards of the city, gig posters are a street-level reminder of the artists, musicians, and spaces that make the underground—all new incarnations of the fiery spirit of music in the District of Columbia.

Although Washington, D.C., is more often known for its monumental landmarks than its musical ones, it has a rich history of local music and the visual art that accompanies it. Go-go and hardcore punk, which both originated in the district and have a storied history of fighting to stay here, laid the groundwork for an independent scene which still thrives today.

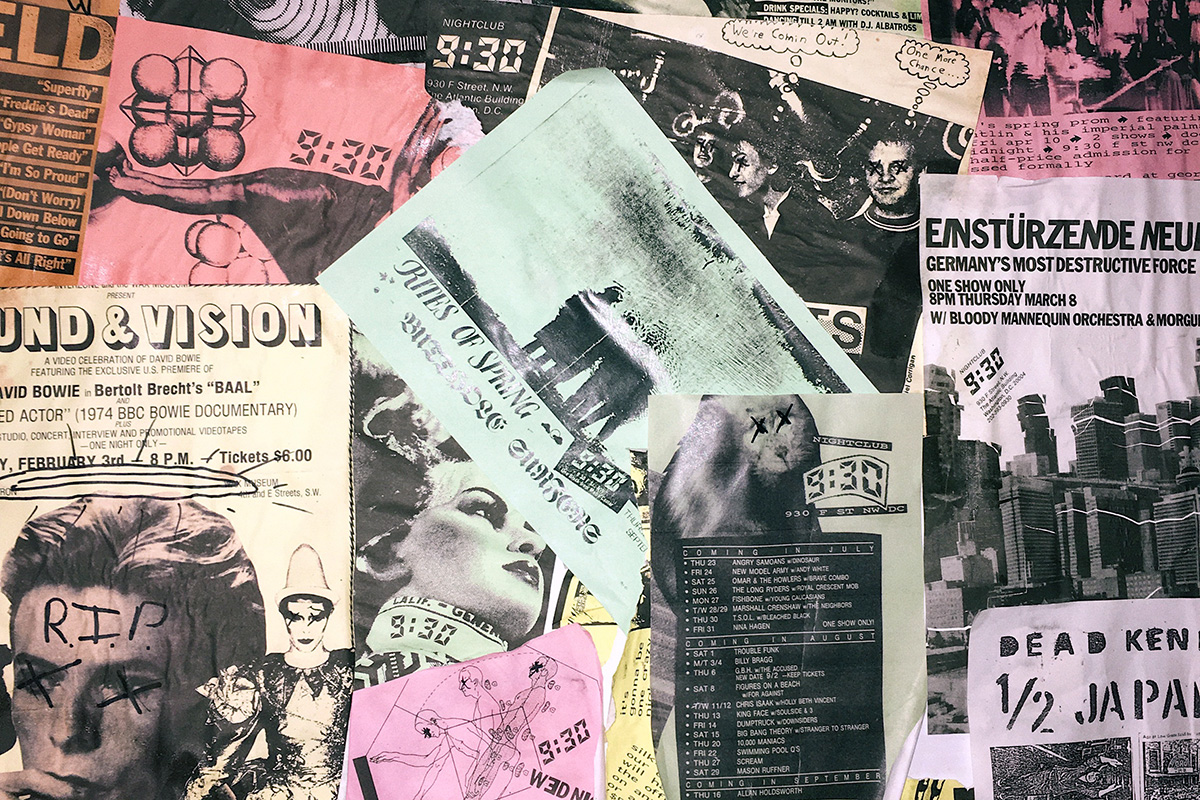

Punk and hardcore shows were often promoted through flyers, which were traditionally made in a black-and-white photocopied collage style, often with no logos and minimal details—more of a heads up than an advertisement. Flyers were posted around the city as well as distributed through zines, a form of low- to no-budget alternative media which allowed punk artists to subvert gatekeepers of commercial publications.

“Postering for shows may seem quaint and antiquated in a modern sense, but if they are posted in a place where a potential audience can see them, then they might work,” says Matt Moffatt of Smash Records, a punk record store that has been in D.C. since 1984 and maintains a bulletin board of strictly black-and-white flyers. “Even if they don’t work as an advertisement, they will become a tactile artifact of the event after the fact.”

One factor keeping the musical culture of D.C. alive is that the city is home to many independently owned music venues—an increasing rarity nationwide. Rising costs and buyouts have dogged venues across the country, despite touring being the most feasible source of revenue for artists after the boom of streaming.

As a result, many venues have ended up in the hands of global corporations like Live Nation and AEG. Webster Hall in New York City was the largest independent music venue in the country until 2017, when it was bought out by AEG and Brooklyn Sports and Entertainment.

Lucky for music fans, D.C. has mostly avoided the grasp of these corporations. Even larger rooms like the punk institution 9:30 Club, Lincoln Theater, and The Anthem are owned by locally based company I.M.P., one of the only remaining large independent promoters in the country. Independence allows venues to choose who they book and when, as well as the freedom to collaborate with others.

DIY venues like Rhizome DC and Dwell also provide a space for musicians, visual artists, and other creatives in the city to perform and learn outside of traditional venues.

“While there’s not really an abundance of DIY spaces in the city, the ones that get it right really get it right,” says Ryan McKeever, a D.C.-based artist who has designed show posters for Rhizome, Dew Drop Inn, Pie Shop, Comet Ping Pong, and more. (Dwell was shut down by the city in late 2019 but plans to reopen after being brought up to code, presumably after COVID-19.)

Morgan Seltzer is a full-time graphic designer for 9:30 Club and I.M.P. “It’s interesting to see the juxtaposition,” she says. “With DIY shows, there’s a bigger emphasis on artistry, and you have much more creative freedom as a promoter.”

The abundance of local venues fosters a creative community of artists whose posters adorn streets and online listings. By combining the styles of venues, musicians, and artists, show flyers are unique snapshots, providing a visual aspect to the sounds of the city.

Paul Joyner, an artist who has designed flyers for flamboyant Baltimore rapper TT the Artist as well as local punk gigs, cites the mixing bowl of cultures as what sets the city’s music scene apart. “D.C. is a galaxy. The music is just one dimension,” he says. “There are so many landmarks, so much legend and lore. Most important, interesting people.”

Joyner, whose style was largely influenced by D.C. punk legends Fugazi, strays away from digital programs and instead prefers a photocopier to make his minimalist, mostly monochrome flyers. “I just put the bare minimum information: time, cost. No logos, advertising. Just come to the show,” he says.

Just as the city is a mixing bowl, the music community overlaps as well: no one is just a musician or a designer or a booker or a host. “What makes the scene so special to me is how collaborative it is,” Seltzer says.

McKeever started making posters as a teenager for his own bands and later for bands that he booked, ultimately leading to his career as a graphic designer and touring musician. “It’s one large network across the country of very talented musicians and designers,” he says. “Word of mouth is very powerful.”

The scene hasn’t survived by sheer luck or been held up purely by its predecessors. The tireless work of venue owners, booking agents, artists, performers, and the audiences who turn out to shows have all helped the city’s music scene stay independent, as well as keep its tradition of political advocacy and activism alive.

“The stars of the DMV scene are the independent promoters and event programmers like Capitol Sound, Queer Girl Movie Night, Underground Orchard, and Dyke March, who work really hard to create space for POC, LGBTQ+ and underrepresented artists,” Seltzer says.

In 2018, Seltzer and friends collaborated to found Concert Moms, a collective that designs merchandise and posters, promotes tours, books shows, and more for up-and-coming artists. “We wanted to put on the kind of shows that we wanted to see, and to push back against how white and male-dominated the industry is,” Seltzer says. “Through Concert Moms alone we’re contributing to a little piece of our own history within D.C. music.”

Here at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, we are creating an interactive music map of D.C., inviting users to upload show posters, photos, and audio recordings. The DC Public Library also has archives for both go-go and punk, and Seltzer says she’s considering starting her own archive for Concert Moms to preserve their history, too.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the ability to come together through live music has been sorely missed. Independent venues are at an even higher risk as they face a grim outlook for the next year of live music. Artists’ troubles are compounded as well—most musicians won’t qualify for unemployment, despite seeing a huge loss of income. However, the music community is adapting: selling coffee and records to go, livestreaming tutorials and performances, and dreaming up new ways for artists and listeners to interact.

Show posters may feel like relics of the past, but surely they will return to the streets of the district. The backs of our hands will be Sharpied and stamped, the wristbands will be put on just a little too tight, the lights will dim and a rush of sound will fill the room once again.

D.C.’s gig posters are important documents of live music in a specific place and time—open invitations for anyone who loves the communal experience of a live performance, and a reminder that the music community is an ever-changing organism.

“Even if they don’t come to the show, they will have a hard time throwing away the flyer,” Joyner says.

Sophie Sachar is a marketing intern at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and a graduate of Boston University, where she studied mass communication and worked at campus radio station WTBU. Previously, she interned at D.C. venues 9:30 Club and Songbyrd Record Café & Music House.