Unter Soreles vigele

Shteyt a vayse tsigele.

Di tsigele iz geforn handlen

Rozkhinkes mit mandlen.

Vos iz di beste skhoyre?

Der khosn vet lernen toyre.

Unter dem kinds vigele

Shteyt a vayse tsigele.

Di tsigele vet forn handlen:

Rozhinkes mit mandlen.

Under little Sarah’s cradle,

There is a little white goat.

The little goat has gone off to sell

Raisins and almonds.

What’s the best merchandise?

Her groom will study Torah.

Under the child’s cradle,

There is a little white goat.

The little goat will go off to sell

Raisins and almonds.

At one time, this sweet little song was alive on the tongues of mothers around the Yiddish-speaking world, as they rocked their infants to sleep to its melody. By the time I stumbled upon it, the world had largely forgotten the song. Yet there it was, fixed in notes printed upon delicate, browning paper. The booklet’s binding frayed, lying in an archival box on Sixteenth Street in Manhattan.

During spring 2017, my work curating concerts had led me to briefly taste the archival profession. The music scholar Neil W. Levin had donated a collection of manuscripts and personal papers of the composer Lazare Saminsky to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. I was intrigued and offered to bring some of its little-known treasures to the public. As a composer myself, I was particularly curious to get to know the work of another classically trained musician engaged with Yiddish folklore.

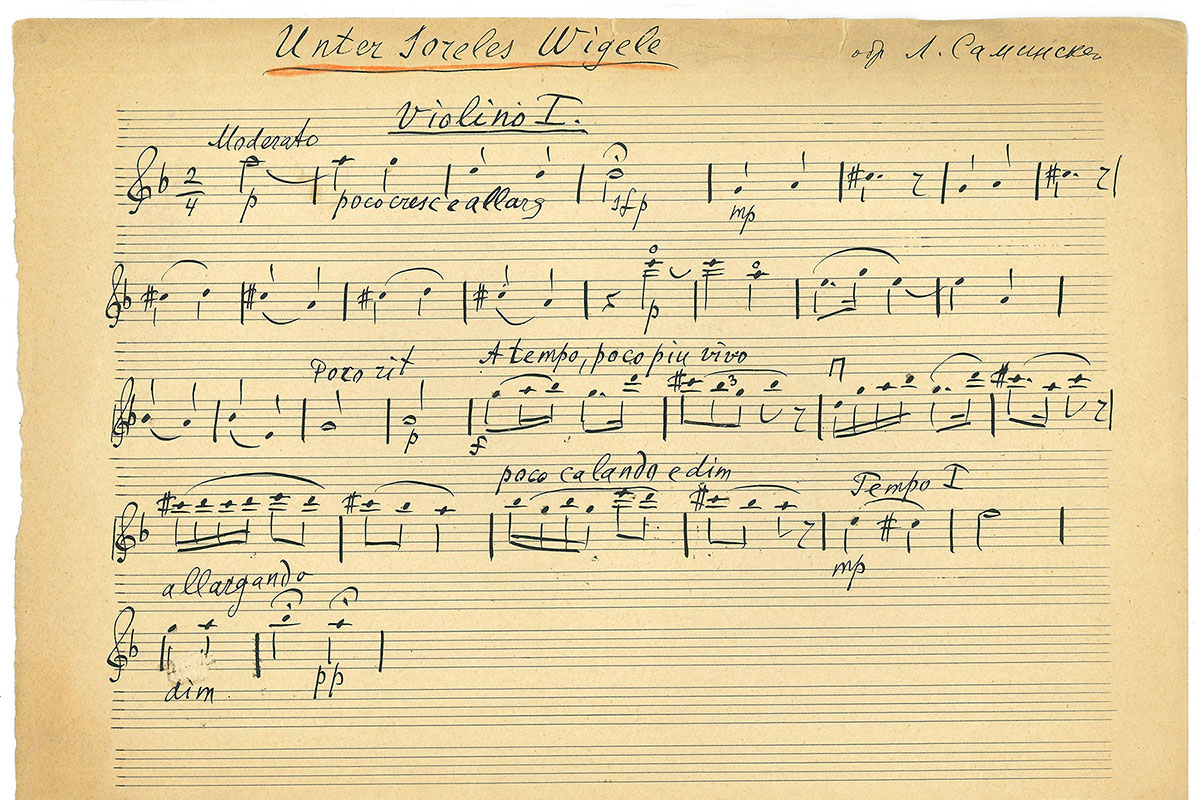

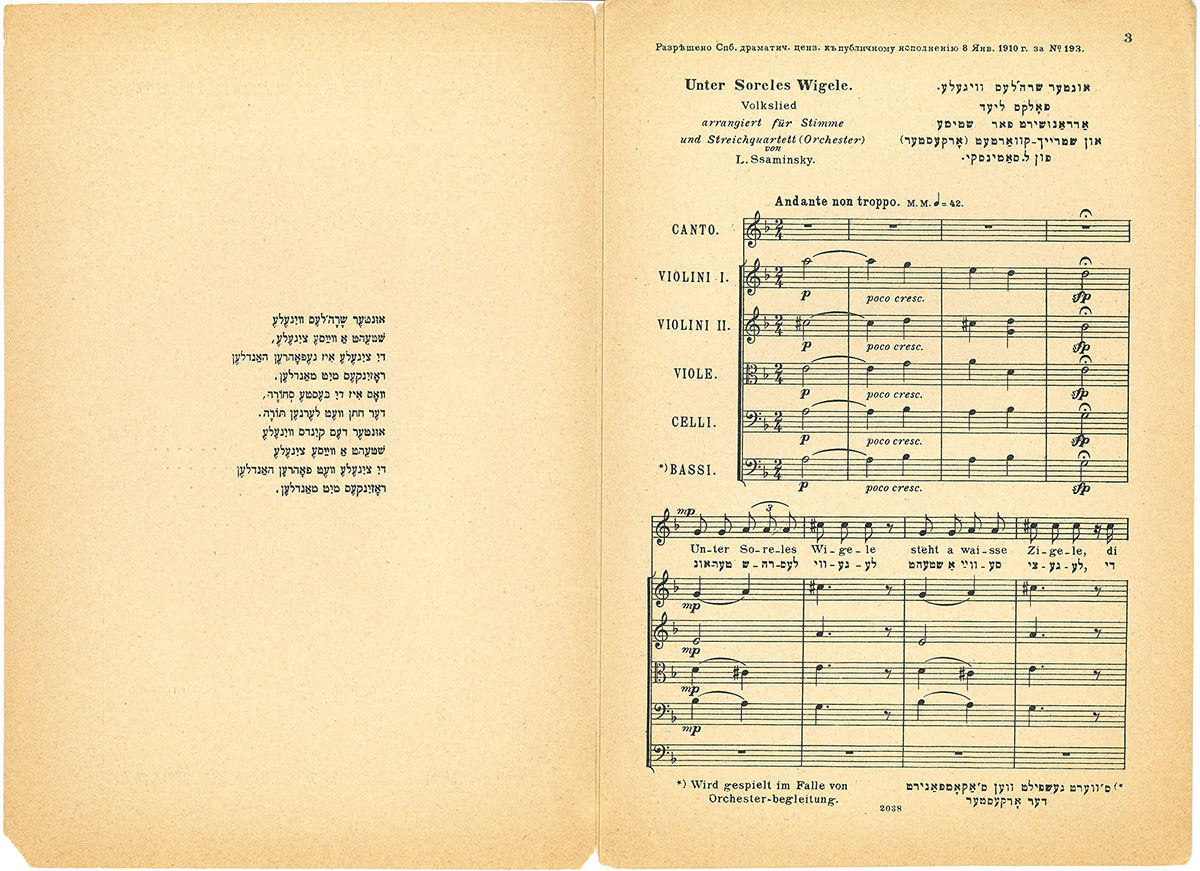

I sifted through old sheet music, manuscripts, typescripts, newspaper clippings, letters, contracts, receipts, flyers, and publicity photos. Buried within these boxes, I found a score and parts from 1910 for a Yiddish lullaby called “Unter Soreles vigele” (Under Little Sarah’s Cradle) arranged for a singer with string quartet or string orchestra—the very song that begins this story.

The haunting lullaby is attested in multiple variants in Peysekh Marek and Shaul Ginsburg’s seminal 1901 text, Evreiskiia narodnyia piesni v Rossii (Jewish Folksongs in Russia). This book was the first large-scale attempt to document Yiddish folksongs. To create it, Marek and Ginsburg placed announcements in newspapers asking for readers to send in Jewish folksongs that they knew. Folksongs don’t exist with one authoritative version; their words and melodies aren’t set in stone. To celebrate and preserve this diversity, their book presented variations for many of its songs.

Instead of describing Soreles vigele (little Sarah’s cradle), some versions of the lullaby refer more abstractly to dem kinds vigele (the child’s cradle) or mayn yingeles vigele (my little boy’s cradle). Some of the goats are klor-vays (pure white) while others are gilden (golden). In all of the variants, Torah study is touted as an aspiration. Some add the wish that the child will write sforim (sacred texts) and attend kheyder (school for traditional religious instruction).

Though these songs changed with time and place, the effort to collect and preserve them underscored the view that these folksongs are no less important than music written in a more fixed form with known creators. In fact, in some ways, they may be more so. Marek and Ginsburg’s work was a landmark in the budding scholarly and musical movement to assert that, in the everchanging Jewish world, these songs deserve to be known, studied, and sung.

In our time, many people are more likely to encounter Yiddish folksongs in an archive rather than sung in the domestic situations that gave rise to them. During Yiddish language’s heyday in the 1920s and 1930s, there were an estimated ten to eleven million speakers around the world. The majority of Yiddish-speaking Jews were based in Eastern Europe, but a sizable community also existed in North America, as well as smaller communities in Western Europe, British Mandate Palestine, South America, and elsewhere. Yiddish declined tremendously with the murder of millions of Yiddish-speaking Jews in the Holocaust as well as due to linguistic assimilation in places like the United States.

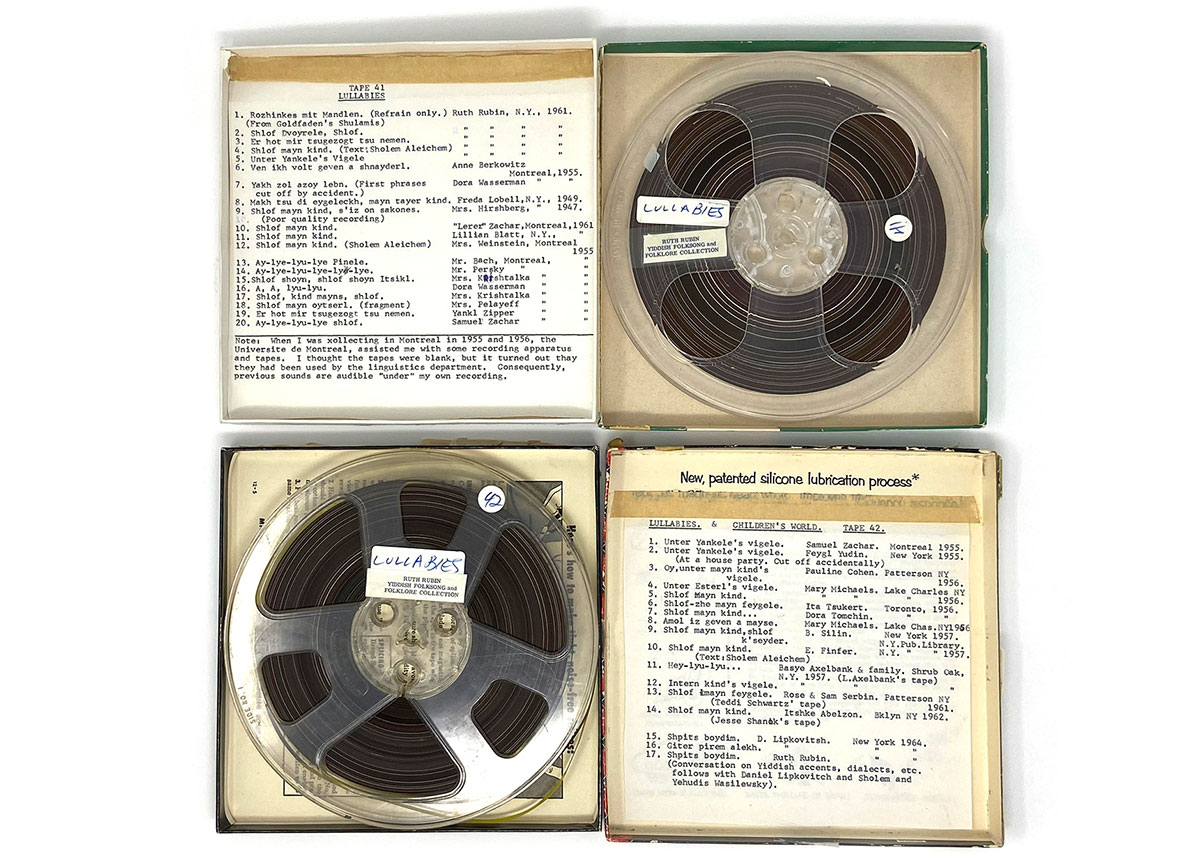

The oldest testaments to Yiddish folksong are through written sources. In other cases, we may hear Yiddish folksongs, direct from the mouth of the folk, through archival audio recordings. Ruth Rubin’s folksong collection at YIVO with over 2,000 recordings contains at least a half-dozen examples of this same lullaby.

Recorded in the 1950s and 1960s in New York and Montreal, these recordings represent a rich diversity of Yiddish dialects and textual variations that provide other endearing names for the child: Esterl (little Esther) and Yankele (little Jacob). These names, all quintessentially Jewish, point to the idea that the child of the lullaby is an archetypal Jewish child. Though most of these singers wound up in New York, their Yiddish accents reveal that they came to the New World from diverse corners of Eastern Europe, each bringing with them a unique version of the same song.

Whether preserved in notation or in recording, archiving a folksong takes it out of its original context and freezes it into a static form that may be safeguarded. Although it is music’s vitality that moves us, a kind of sterility is required for preservation.

Music notation may flatten out nuances of singing, phrasing, and inflection that are subtle and yet no small part of the beauty of the original. We are left with directions for a performance, not the thing itself.

Recordings, on the other hand, capture some of that subtlety while elevating the contingencies of one particular performance, including vocal imperfections, memory slips, and all the ways that singing for a microphone may change what would otherwise be an intimate, domestic performance. We have a snapshot of one beautiful moment—perhaps posed for the camera, so to speak—without the ability to sing back, ask a question, or hear it again a bit differently.

However, through the combination of sources at our disposal for this particular song, we may piece together a rich picture of the song through time and of Yiddish folksong in general. We have extant documentation, in one form or another, of thousands of different Yiddish folksongs. While these songs may be beautiful and moving in and of themselves, like “Unter Soreles vigele” they are also of tremendous significance for what they tell us about Jewish life and Jewish history. The symbols, ideas, and values that they explore are a window into the Jewish past through the very words of the people who lived it.

And yet for Yiddish folksongs to impact modern audiences, it is not enough for these songs to sit in the archives: we must keep singing them.

In our time, most of those interested in Yiddish folksong are not native speakers and didn’t learn these songs through the natural process of domestic dissemination the singers recorded by Ruth Rubin would have. Archives play a crucial role in making this repertoire available to singers, instrumental musicians, and composers.

While lovers of Yiddish folksong mourn the discontinuity of its oral transmission, our distance does bring with it some advantages. Those curious about Yiddish folksong today have at their fingertips a vast array of variants and information from which they may mix and match. Coming with a little distance, practitioners may consciously decide how they would like to relate to these received texts of the past. Do they want to study a variety of documents and recordings and reproduce as faithfully as they can the way a song might have been performed in the past? Do they want to take only a kernel of a folksong and use it for the creation of something completely new?

This may seem like a contemporary dilemma, but it goes back more than a hundred years. Saminsky’s 1910 “Unter Soreles vigele” was published by the Society for Jewish Folk Music, an organization founded by a group of musicians at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1908 with a mission to support Jewish ethnographic and compositional work through fieldwork, publishing, concerts, and lectures. The publications of the Society for Jewish Folk Music attest to this same range of approaches. Some of their publications were meant to present folksongs with ethnographic precision while others used folksongs as creative fodder. Composer and violin virtuoso Joseph Achron’s 1914 “Hebreishe viglid”(Hebrew Lullaby) for violin and piano is a great example of this kind of creativity, and it uses “Unter Soreles vigele”as its inspiration. The short showpiece starts with a straightforward presentation of the melody, which it then freely varies, elaborates, and embellishes.

An even more imaginative take on the lullaby may be heard in Stefan Wolpe’s arrangement, premiered in Berlin about a decade later. Wolpe’s adaptation is based on a version published by Fritz Mordechai Kaufmann in his 1920 book Die Schönsten Lieder der Ostjuden (The Most Beautiful Songs of Eastern European Jews). While Wolpe’s arrangement features a faithful presentation of the song’s melody and text by the vocalist, the piano offers a striking unconventional accompaniment of hazy chromatic harmonies and strident, angular dissonances.

Today there is a variety of talented singers, instrumental musicians, and composers dedicated to Yiddish folksong who are creating historically informed performances and arrangements, wildly imaginative, vital pieces inspired by Yiddish folksong, and everything in between. Their passionate work—like that of Saminsky, Achron, Wolpe, and others in previous generations—helps to process this repertoire’s meaning and significance for contemporary audiences and to keep it alive in changing contexts.

In March 2022, YIVO featured a festival with four concerts showcasing some of the diversity of musical engagement with Yiddish folksong today. The festival included performances from over thirty artists and the premiere of over a dozen new classical works inspired by Yiddish folksong. We’re thrilled to bring a performance of works featured at that festival to the National Mall and livestreaming around the world as a part of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on July 6 at 2 p.m.

Alex Weiser is the director of public programs at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the composer of and all the days were purple, an album of songs in Yiddish and English that was named a 2020 Pulitzer Prize Finalist for Music.

For nearly a century, YIVO has pioneered new forms of Jewish scholarship, research, education, and cultural expression. The YIVO Archives contains more than 23 million original items and YIVO’s Library has over 400,000 volumes—the single largest resource for such study in the world.