When I first opened Thunderbird Strike on my phone, I expected an Oregon Trail-style story game. Knowing only its premise of oil pipeline development on Native lands, I expected long paragraphs of explanation—“You are a water protector protesting the building of pipelines…”—and a list of instructions and information on how to keep my character alive and move through the game.

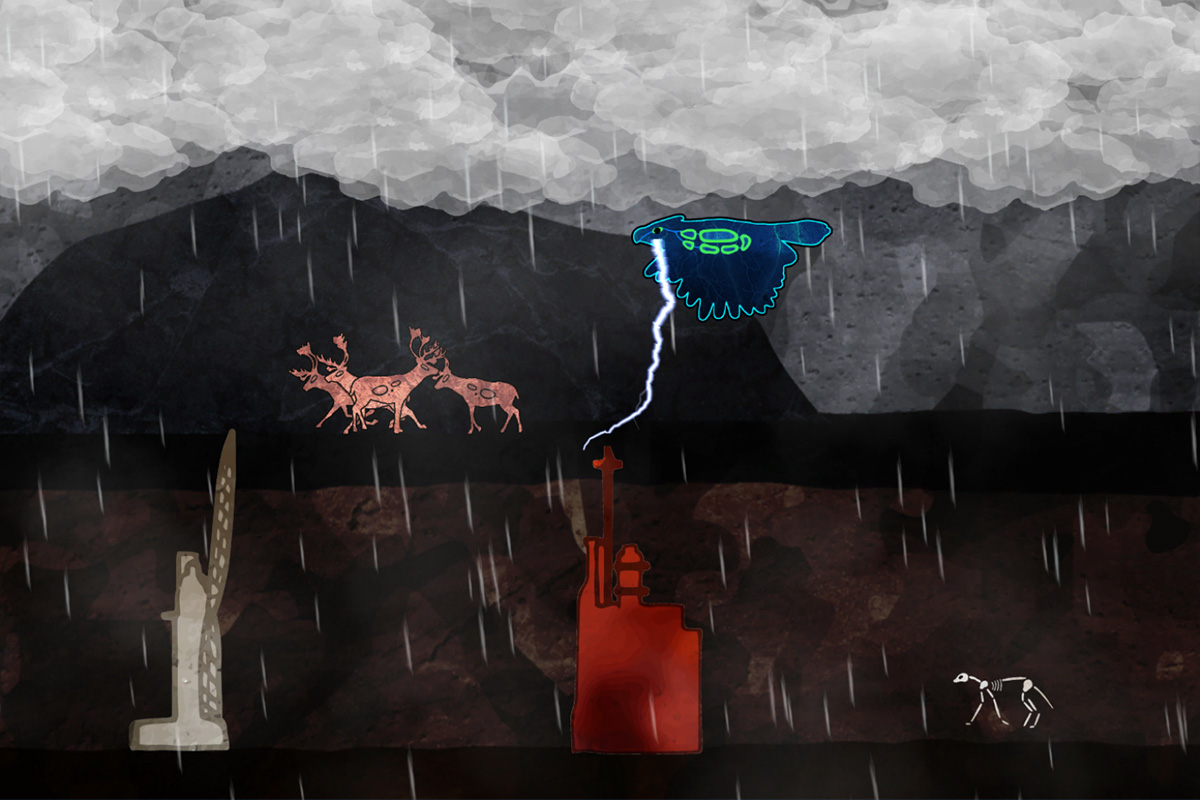

To my surprise, it opened simply with a short stop-motion animation, with no words or text, only buffalos, deer, and thunderbirds moving through a landscape being built up with oil pipelines and factories. It gave me only three instructions: tap screen to fly, fly into clouds to gather lightning, tap thunderbird to strike. I easily figured out how to destroy construction trucks, but it was a long time before I realized I could use lightning to revive the animal skeletons scattered between them.

I mentioned this to the game’s creator, Elizabeth LaPensée, who responded with a warm laugh. “It’s okay to see Thunderbird Strike through your lens. It’s your journey.”

Animation: Elizabeth LaPensée

LaPensée (Anishinaabe, Métis, and a little Irish) is a professor in the Department of Media and Information at Michigan State University in East Lansing. She creates video games inspired by her indigenous heritage to help heal intergenerational trauma. She says her people have a saying: “a truth from the heart,” meaning each person has their own form of truth.

“I try to create autonomy in Thunderbird Strike, where you can focus on restoration or destruction,” she explained. “It doesn’t judge you for those decisions. Ultimately you get a high score.”

When creating the game, LaPensée knew that not everyone would fully understand the cultural significance of thunderbirds and buffalo. Players will understand what they need to understand and interpret their own meanings from the visuals and scenes in the game, she believes.

“We don’t need to spoon-feed culture to people,” she insisted. “It’s an important aspect of our sovereignty that we are able to express ourselves at the level we want to, not on behalf of trying to reach everyone all the time.”

That’s part of why LaPensée left her role as a consultant in the video game industry, where she says creators try to change or adapt culture to make games more accessible to a wider audience. She also found that indigenous artists aren’t hired as artists, only as consultants, so they don’t get to create their own work. Through workshops and outreach programs, Native artists are earning meaningful roles in game design, becoming prominent figures in the indie game world.

“They can innovate on mechanics, game experiences, and game play in ways that are reflective of indigenous ways of knowing.”

Games for Educating

When white educators lead STEM programs in Native communities, they often assume that science, math, and technology are new concepts, but LaPensée reminds us that communities pass teachings down through generations in other ways.

To combat the misconception that indigenous knowledge has no value in the technological age, she created a new game development workshop for youth called Generative Generations. Students must create a game idea, and then incorporate elements of indigenous science assigned with “activation cards.” These young designers have to use indigenous knowledge about water, physics, blood memory, land, particle systems, and other teachings to develop mechanics of gameplay.

The workshop aims to show youth that indigenous science is a valid form of knowledge—and ultimately change how Native Americans perceive themselves. LaPensée wants Native people to be able to refer to themselves as “indigenous scientists.”

Games for Healing

Through her work, LaPensée is also exploring how Native value systems can be used to create more engaging and thought-provoking games. As an example, she described board games where players discard worker characters when no longer in use.

“That’s not how we should treat people,” she said. “The worker should stay through the whole game unless something happens to them.”

Animation: Elizabeth LaPensée

When she first developed Honour Water, an Anishinaabe singing and language-learning mobile game, she followed the industry model of one player competing against another. But when she presented it to Anishinaabe elders, they didn’t want it to be competitive. For so long, their people were shamed for speaking their language, and now the new generations are shamed for not speaking it because they haven’t learned it. She removed the competitive aspect of the game, reducing young people’s hesitation to learn their ancestral language.

“Indigenous people have always had games about reinforcing teachings or passing on teachings, resolving conflict,” she reflected. “Games are an integral part of our communities.”

Even with the desire to innovate, LaPensée finds value in working with classic video game frameworks. Her mobile game Invaders, based on the classic Space Invaders, addresses European colonizers in America. In Space Invaders, your remaining lives are shown as little pixelated tanks. In Invaders, your life count is represented by real people. When you’re hit, you lose one of your warriors. There’s no way to bring them back.

“There were not replenishable lives during the process of colonization.”

For Native communities, LaPensée’s games are powerful tools for healing. Recounting traumatic experiences in traditional therapy can cause further trauma, leading a person to avoid their past and repress their feelings. But in a virtual environment, people to experience memories and history in a controllable way, progressing—or pausing—at their own pace.

Games of, by, and for the People

Although she creates games for the general public, LaPensée shows how Indigenous America is not threatened by twenty-first-century digital culture—it is thriving with it. Respecting indigenous knowledge as an equal to Western science can lead to the creation of digital spaces where the wounds of colonization can be examined and even mended.

When LaPensée first introduced the idea of using video games for education and healing in Native communities, some had concerns about youth being glued to screens instead of going outside. She has found that when adults shame youth for using smartphones or computers, the youth resist and are pushed farther away from their cultural heritage. Given the freedom to choose, they find a balance between using technology and spending time outside. Others in the community were hesitant about using devices they were unfamiliar with. Taking that into account, Honour Water and LaPensée’s other language games are designed to be intergenerational, so grandparents can play along with grandchildren.

Animation: Emma Cregan

By listening to concerns and facilitating a reciprocal creative process, LaPensée has built trust with Native communities. She creates games to help Native people find healing and pass down their knowledge, not for her own personal gain, and she uses workshops to empower Native Americans to create their own games and kick-start careers in gaming.

One crucial element of LaPensée’s practice that she hopes others will follow is accessibility—both in playing and creating.

“I know what it’s like to live in a place where you cannot stream content,” she assured. “I know what it’s like to drive twenty or thirty minutes into town to sit outside the community library to use the Wi-Fi, sending files to get my work done, and receiving files. Then driving all the way back home and then working.”

Instead of relying on complex computer-generated imagery, she incorporates traditional animation techniques, hand-drawn work, photography, and other accessible art forms into her video games. For Thunderbird Strike, she created textures using photos of real copper and real water. The texture of the tires on the construction trucks is from a photo of tires on an actual truck at a pipeline construction site. By utilizing these techniques, she shows how traditional culture and digital media can work in harmony. The tactility of the real life textures shown in the photos and hand drawn animations give Thunderbird Strike a tangibility that emphasizes the reality of the struggle to protect Native lands from oil pipelines.

She also advocates for the creation of free mobile and online games. Industry games are created using millions of dollars, and then are sold at high prices. Games can’t be used to start difficult discussions or heal past trauma if no one can afford to make or buy them.

As a responsible designer and educator, Elizabeth LaPensée has become a trusted leader in the indigenous gaming world. She believes that digital gaming can be an accessible form of art, and that the more indigenous artists get involved, the more conversations we can have about the Native American experience through virtual interactive storytelling.

Emma Cregan is a filmmaker and a former video production intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.