Since the 1970s, the neighborhood of Flushing in Queens, New York, has grown into the largest community of Chinese immigrants in the Eastern United States. Census data paints a flow of dreams and ambition from East Asia to the East Coast: as of 1980, Asian Americans accounted for roughly 12 percent of the total Flushing population. By 2010, it expanded to more than 66 percent.

But numbers only offer a blurry, monochromatic view of a place. It is the many stories of its residents that add the layers of color pigments.

The Chinese-to-New York immigration stories are not a homogeneous tale, though crowded basement apartments and low-paying dishwashing jobs may resonate with the memories of many. Migration stories do not always have a happy ending. Does a story like that end at all? At the end of one’s life, the story is usually carried on by loved ones. But what if those stories are never passed down?

This is a story about how the streetscape of Flushing has helped me (re)imagine my late fathers’ untold immigration story.

Pacing through Flushing on a brisk fall morning, I feel the hot fumes rise from manhole covers as they make their way out onto the streets. It’s a busy scene accompanied by countless Chinese dialects. Sitting on the stairs that lead up to the Queens Library, dipping my 油条 (youtiao, Chinese fried churro) into my 豆浆 (doujian, Chinese soymilk), I realize it’s not my first time here.

Thirteen years ago, I was here with my father. The sound of buzzing streets carries me like white noise into my memories. I recall that in my last year of high school, I received a letter from my father handwritten in simplified Chinese. It read: “There is so much I wish to tell you, but for now, happy birthday.” Looking at that letter now, I think if handwriting had choices for fonts, this would be written in italics because the characters look so distant and fragile.

While I take another bite of my breakfast, I look across the street at a bright red sign: Qingdao Restaurant. I was born in Qingdao, a major port city in China. When I took my first breath at the hospital, my father was likely sleeping below deck in a damp-smelling crew’s quarters with other sailors. That part I can imagine because I have also worked on a ship. A sense of mystery always shrouded his existence. I knew very little about him, and maybe that cruise ship job was my attempt to share an experience at different points in time.

Lost family photos tell me that I was cradled in my mother’s arms when I met him on a gangway at the Port of Shanghai. He stayed with us for a while then, but that would be one of my last recollections of him until our reunion eleven years later in New York.

“Your father went to America. You will move there soon too.”

This was the story I lived with during my childhood. I imagine my father told a similar story, most likely in English in a city by the name of 纽约 (Niǔyuē, or New York). My father was a firm believer in the Chinese phrase 报喜不报忧: tell stores of happiness, not stories of worry. Perhaps, for this reason, the phone seldom rang, and the mystery around him remained as clouded as ever, although he always managed to send us money. I used to think that once I got my own job, I would buy a big shovel and dig a hole to the other side of the world to see him.

Turns out, before I had the chance to dig that hole, my father picked me up at John F. Kennedy International Airport on the humid summer day in 2006. I spent the next few days at his friend’s house in Flushing. Even as a child, it didn’t take long for me to realize that Flushing is a place where stories don’t need to be told in English. Each morning, my father would drive me to Main Street to fetch authentic Chinese breakfasts from a hole-in-the-wall restaurant. The curb where he would park the car and and leave me waiting left a strong impression. At least the food kept a sense of familiarity amid the jet lag and uncertainty of literally everything else.

My father didn’t tell anyone that business was rough. He eventually took up long-distance trucking. We moved frequently, finally settling in Hacienda Heights in Los Angeles County, known for its large Chinese community. As I grew up, my father grew tired and fragile. Years of toil and isolation had taken its toll.

When my mother’s immigration papers finally came through, even our reunited family didn’t have the healing powers of medicine prescribed by a doctor. Years of trying to fit the puzzle together did not do the trick. It also didn’t help that mental health is a taboo subject in the common Chinese household. My father never became a naturalized American citizen; a green card was enough for him. He moved back to Qingdao in 2014. Our contact once again turned seldom.

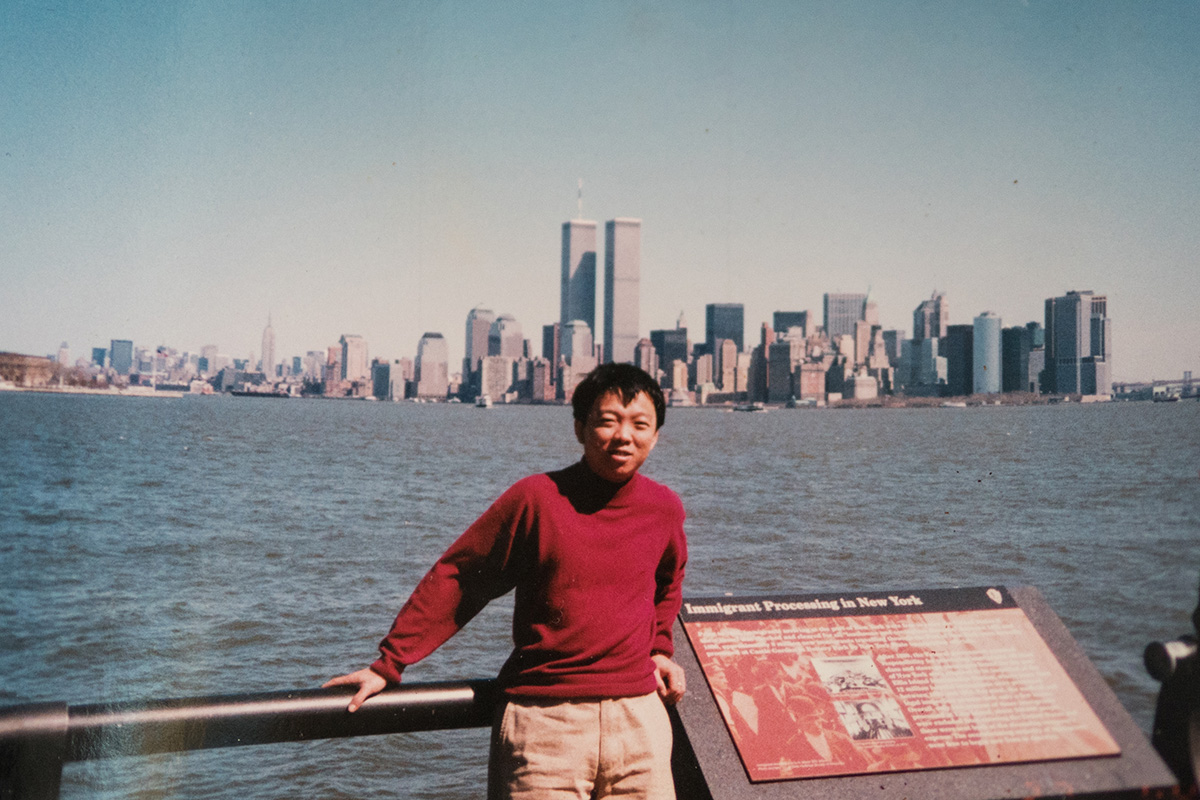

In 2017, “He left.” It’s something we say in Chinese, a euphemism for when someone has passed away. Since then, the Earth has continued to revolve around the Sun, about two times and counting. He passed away in the room where I spent most of my childhood weekends. On a visit back to Qingdao, I had thirty minutes to salvage the tangible pieces of a person’s entire life, at least the remainder of what he brought back from America: his expired green card, photos of me from my childhood, and pictures of his days in Flushing. Ironically, I brought what I found back to America. I’m not sure what the cleaning company did with the rest.

I now write this in Washington, D.C., and an unspoken perk of interning at the Smithsonian is its proximity to New York. During the first few weekends of my internship, I made trips to Flushing to satisfy my cravings for Chinese food. It was during my first visit, on a sunny Saturday, that I noticed the hole-in-the-wall breakfast restaurant that my father took me to my first week in the United States.

It rekindled the long-forgotten memory of mine that my father once was a part of this streetscape. It instilled a sense of strength and purpose as I, for the first time, flipped through the dusty photos since I salvaged them from his room. I wanted to reach out and connect with him. Out of the pile, two photos had Chinese business signs in the background. Later on, thanks to a dear friend from Flushing, we pinpointed the locations and paid them a visit.

In a 2018 article in Geographic Review, Shaolu Yu examines Flushing as a place where Chinese immigrants settle, using it as a launch point for her imagining of America. She points out that it isn’t rare for Chinese immigrants to be taken straight from the airport to Flushing and be thereafter confined within its boundaries. There’s an intimate relationship between Flushing and its Chinese inhabitants, “the imagined home far from home.”

Images from my father’s struggle with mental health and his funeral have always plagued my memory of him. For the longest time, I could not imagine a smile on his face. But being in Flushing, standing in the same spots as he once did, looking at him smiling in the photograph garnished with hope, I have managed to salvage the happier memories. Reflecting on the birthday card he wrote to me years ago, I am grateful to still engage with his story even though he has passed.

I now remember sitting next to my father in his truck as we drove across the United States from Norfolk to Los Angeles. I remember two things from the long drive: the seemingly endless rows of icicles in the cold Oklahoma winter, and his American Dream. In times of uncertainty, he found refuge in dreaming about the future. He dreamt of a time when we would stop paying rent and start paying property tax on our very own house.

This year, my family paid our first property tax.

Meanwhile, Flushing continues to nurture the dreams of countless Chinese immigrants.

In memory of my father.

Shou De Zhang is a cultural sustainability intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. He is a Chinese-born American student at Wageningen University & Research pursuing a Master of Science in tourism, society, and environment, with an emphasis on global change.

References

Yu, Shaolu. 2018. “‘That is Real America!’: Imaginative Geography among the Chinese Immigrants in Flushing, New York City.” Geographical Review: 108(2), 225-249.

Shen, Muyao. 2018. “Flushing, N.Y.: Where Mainland Chinese Immigrants Are Moving In.” Medium.