How do we unpack a life? When people move to a new place, they carry with them things from the places they left behind. Whether their move is voluntary or involuntary, they bring stories and memories of their previous lives, as well as customs and traditions they sustain in their new homes. They treasure certain tangible objects that serve as powerful touchstones for the paths they or their families have traveled.

Many such objects evoke affectionate memories that connect the past with our present. Other memories leave us deeply conflicted.

I have always marveled at how my dad started his life completely over when he emigrated from China to attend university in the United States. But because he died when I was nine, most of my knowledge about him centers around my brief childhood with him in America. I know nothing about his boyhood in China; in fact, I don’t even know his parents’ names. So, a sense of my own Chinese heritage is incomplete.

Immigrants often experience two lives simultaneously, balancing the life they knew before with life in their new country. But what if your father died before you were born? How would you connect to your father’s heritage if you never knew him at all?

I pondered these questions when I met my neighbor, Abiye Abebe Jr., who emigrated from Ethiopia to the United States as a teenager in 1990. Almost two decades earlier, in 1974, the Derg military junta staged a violent overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie’s administration. That same year, one month before Abiye was born, the Derg assassinated his father, one in a group of sixty men.

“I grew up in Ethiopia under the rule of the Derg regime and only had snippets of information about my dad’s life,” Abiye explains. “My mother told me that Ababi [“Dad” in Amharic] had been killed, and my school history classes taught me about the Derg’s overthrow of Haile Selassie’s government. As a young boy, I did not fully comprehend that the Derg had executed Ababi by firing squad.”

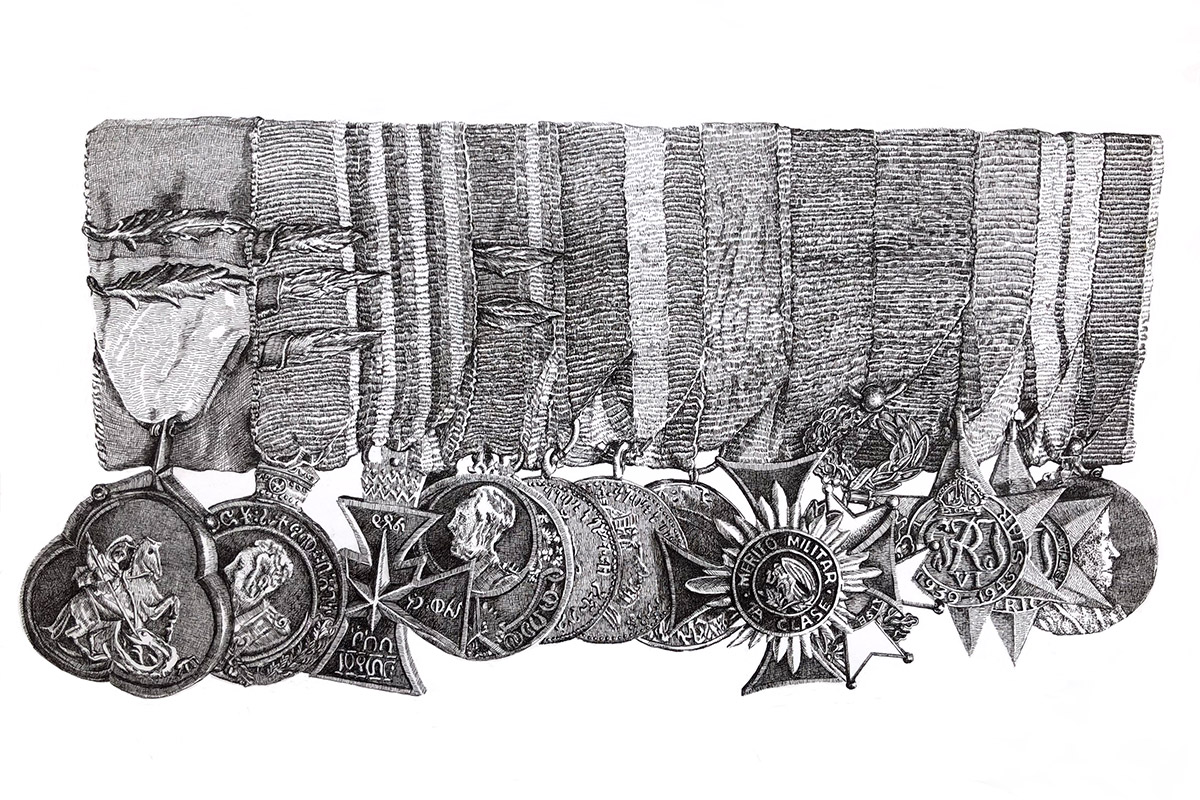

Only by contemplating his father’s uniform medals did Abiye Jr. begin to connect with the soldier’s story and the immensity of his life.

Lieutenant General Abiye Abebe—known by his colleagues as General Abiye—had gained the attention of Haile Selassie in 1934 through his active resistance against the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, so Selassie requested his presence during the Ethiopian exile in Bath, England (1936–1939). General Abiye held a slew of positions, from his military service in the Battle of Maychew in his twenties to Minister of War in his thirties.

“I learned about my father’s bravery through The Order of the Holy Trinity medal, awarded by the Ethiopian government for his exemplary service,” Abiye noted. “But when they conferred other medals two and three times over several years, it became clear to me that he was devoted to his country.”

The Ethiopian wartime medals—The Medal of the Campaign, the Refugees Medal, and the Military Medal of the Order of St. George—were presented to General Abiye multiple times. Some of the medals in General Abiye’s collection deepened Abiye Jr.’s understanding of his Ethiopian heritage.

“My favorite is the Order of Menelik II, because Emperor Menelik II conquered the Italian colonizers in 1896, securing Ethiopia’s independence in the Battle of Maychew,” he noted. “I often compare my father to Emperor Menelik II, because they both had a very progressive vision for Ethiopia. And like Menelik II, my father also defended the sovereignty of Ethiopia by battling the Italian fascist invaders during World War II.”

Haile Selassie came to rely upon General Abiye for counsel. By the time General Abiye was in his forties, he had already served Ethiopia as the ambassador to France (1955–1958), minister of justice (1958–1961), and viceroy of the territory of Eritrea (1959–1961). In the final decade of his life, General Abiye was the president of the Ethiopian senate (1964–1974) and the minister of defense and Selassie’s chief of staff (1974).

General Abiye’s medals weren’t solely contained to Ethiopia, as he accompanied Emperor Selassie on visits abroad to cultivate international relations: the Order of Orange conferred by Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, the Merito Militar 1a Clase from Mexico President Cortines, the Legion of Honor from French President de Gaulle, and the National Order of Merit of France from President Pompidou, as well as the Grand Cross of the Order of Al Nahda from Jordan’s King Hussein. In Great Britain, General Abiye was awarded medals by King George VI, and later the Honorary Knighthood of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire bestowed by Queen Elizabeth II.

“Every time I look at my father’s foreign medals, I feel an affinity with him because he demonstrated how to respect the cultures of other countries,” Abiye says. “As a New American, I understand what it’s like to straddle the culture of my birth country of Ethiopia and also live within the culture of the United States.”

By the time he died, General Abiye had been presented with medals and gifts from thirty countries representing six continents (Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America), all which advanced partnerships between Ethiopia and other nations.

General Abiye married three times and had seven children. His first wife, Princess Tsehai, the fourth child of Haile Selassie, died during childbirth one year later. He then married Woizero Amerech Nasibu, with whom he had four children but would later divorce in 1966. In 1970, he married Woizero Tsige. The couple had two daughters before his death, and Abiye Jr. was born posthumously.

By July 1974, the Derg junta had staged a revolution to overthrow the Ethiopian government. Sixty senior officials from Selassie’s administration were imprisoned with no due process or indictment. General Abiye learned of the Derg’s secret assassination scheme, so during a prison visit, he told his pregnant wife, “You will have a son. Please give him my medals and name him Abiye Abebe Jr. This will be my way of staying close to him, if I am no longer around.”

On November 23, 1974, the sixty men in captivity were executed and placed in an unmarked mass grave. One month later, Abiye Abebe Jr. was born.

A few weeks after his birth, Abiye Jr.’s mother was suddenly taken to prison by the Derg, leaving newborn Abiye and his two toddler sisters to be cared for by their grandmother. “The Derg waited for Mother to give birth, then imprisoned her without due process because she was General Abiye’s wife,” Abiye said. “My grandmother was allowed to deliver food to the prison. She would hide messages in the food, telling Mother that my sisters and I were okay. But the notes were soon discovered by the Derg and discarded before they reached Mother.”

After living without their mother for eight months, in August 1975, the Derg abruptly released her from prison. “As an infant, I was not aware at the time that my mother had been taken away,” Abiye said. “But I do remember a whirlwind of feelings after she returned. So much sadness. Grief over the murder of my father. Mother not being able to see her children while she was in prison. The Derg declared any funerals for those from Selassie’s government to be illegal. Mother mourned the loss of her husband by wearing black clothing for seven years.”

For the next sixteen years, Abiye’s family lived under house arrest, while Ethiopia morphed into a communist state. He remembers people dubbing the new regime “The Ethiopian Red Terror.”

“We had nightly curfews at 10 p.m.,” he recalled. “Satellite offices monitored activity in neighborhoods throughout the city of Addis Ababa where we lived. All personal properties were nationalized, and statues of Lenin and Marx were erected. People would go for days without food because of empty grocery shelves. Our multiple television channels were reduced to one nationally operated channel, and mass arrests were often made for no reason.”

As a result of frequent random house searches, Abiye Jr.’s mother quietly moved General Abiye’s medals to her mother’s house on the outskirts of the city, to ensure they would not be confiscated by the Derg.

The most peculiar situation for Abiye was at his school. “One day, when I was in the eighth grade, I realized that the son of the man who ordered my father’s execution was a schoolmate of mine,” he recalled. “We were in the same grade, but in different classrooms. Our teachers never pointed it out, but it was like the elephant in the room. I didn’t know how I felt about it, because I didn’t live through the revolution. But it was so surreal. After I figured it out, I paid more attention to this Derg president’s son. I noticed who he hung out with, mostly with children of other Derg officials. He would get picked up from inside the school gate, while the rest of us had to wait for our moms outside the school gate. He would get food delivered to the school while we had to bring our lunch boxes. I never interacted with him.”

By 1990, the Derg began drafting teenage boys into their army. Fearing that her fifteen-year-old son would be drafted into the same junta that executed his father, Abiye’s mother devised a plan to protect him by contacting the wives of previous ambassadors from Selassie’s administration, who quickly facilitated a sponsorship through the American Embassy in Addis Ababa for her three children. Daughter Berkinesh was sent to Texas to attend school, daughter Phebe was sent to school in France, and Abiye and his mother flew to Washington, D.C., where she enrolled him in a boarding school in nearby Virginia. Abiye’s mother yearned to keep her home in Addis Ababa, so she rented the house to the Austrian ambassador to Ethiopia. The rent paid for the tuition in her children’s boarding schools.

By 1991, the Derg regime was ousted from power, making way for a more democratic governance. Abiye’s mother returned to Addis Ababa while her children stayed in their respective boarding schools. Abiye learned to speak fluent English. It took eleven more years for him to become a naturalized citizen of the United States. Today, he still lives in Washington, D.C. He has two master’s degrees and speaks five languages.

Over the next decade, Abiye made frequent trips back to Ethiopia to visit his mother and bring his father’s medals back to the United States, where they are now in guarded storage.

“I carry his medals and his name proudly,” he proclaimed. Abiye Abebe Jr. may not have had the same opportunity to know his father the way other kids know their fathers. But General Abiye left a tangible legacy that gives his son a deeper understanding of his family heritage and a more complete relationship with the father he never knew.

Jane Chu describes the contributions of immigrants to America through her stories and illustrations. A practicing visual artist, Chu served as the eleventh chairperson of the National Endowment for the Arts. She lives and works in Washington, D.C.

References

Agstner, R. (2021). Abiyy Abbäbä. Encyclopaedia Aethiopic, Vol. 5, Thomas Rave, (Ed.). University of Hamburg.

Baissa, L. (1989). UNITED STATES MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO ETHIOPIA, 1953-1974: A REAPPRAISAL OF A DIFFICULT PATRON-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP. Northeast African Studies, 11(3), 51-70. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

Marcus, H. (1999). 1960, the Year the Sky Began Falling on Haile Selassie. Northeast African Studies, 6(3), new series, 11-25. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

Chronology March 16, 1961-June 15, 1961. (1961). Middle East Journal, 15(3), 302-325. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

Ministry of Information and Tourism. (1968). His Imperial Majesty visits Asia, the Far East and Australia: April 28 – May 27, 1968. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Pankhurst, R. (1996). Emperor Haile Sellassie's Autobiography, and an Unpublished Draft. Northeast African Studies, 3(3), new series, 69-109. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

Vestal, T. (2003). Emperor Haile Selassie's First State Visit to The United States in 1954: The Oklahoma Interlude. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 1(1), 133-152. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

Vestal, T. (2013). The Lost Opportunity for Ethiopia: The failure to move toward democratic governance. International Journal of African Development, 1(1), 40-56. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

Wesley, C. (1972). Ethiopia. Negro History Bulletin. 35(1), 4-5. Retrieved January 31, 2021.