The African American Craft Initiative was designed to expand the visibility of African American artisans and ensure equitable access to resources. As part of this effort, Folklife Magazine highlights artisans in the AACI network.

Not long after leaving university, Marvin Sin walked into a Harlem bookstore and turned over a title that had been assigned in school as mandatory reading. The Histories, written by first-century geographer Herodotus, captures the culture and politics of Greece, West Asia, and North Africa. Herodotus is considered the father of Western history.

“But they only assigned certain chapters,” Sin says. “In one chapter that they didn’t assign, this Greek historian basically admits that everything coming out of Greece was stolen from Africa. I said, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, hold up. I’m coming out of four years at Columbia University, and I’m just finding this out now?’”

Sin attended the university from 1966 to 1970 but ultimately chose not to finish his degree. “I became aware that I was being prepared to take a position in service of a system that was oppressing the Black community,” he explains. “Now more than ever, it’s becoming clear that the university system is training us to think in certain ways and precluding others.”

He describes the experience of learning at exclusive schools as “being invited to a party, but your friends can’t come.” He chose instead to immerse himself in Harlem, bringing him closer to the creativity and vibrancy of his own culture. This experience brought him to life.

“And what is culture?” Sin muses. “I mean, most people think of it as art, painting, sculpture, drawing, music, dance. But the main thing of culture is agriculture. Education is culture. Health is culture. Sports are culture. Family is culture. Rituals—how people live—are totally contained within the realm of culture.”

Sin embraced the power of culture, and today he is a master leather craftsman and visual artist with over fifty years of experience in arts promotion, entrepreneurship, and economic development.

In the sixties, Sin purchased his first Tandy Leather toolkit, influenced by his roommate. “When I came into the living room, I saw he was putting impressions in the leather,” he explains. “I stopped there for a minute and looked at it. I thought it was interesting, so I went down and bought a skin of leather.” Sin took a position on the floor, punching holes into the hide and occasionally the ground.

“I had just finished designing a set of zodiac cards. Astrology and the zodiac were really fascinating people. Somebody asked me to put a design on a bag. It was off to the races after that,” he says, chuckling. “One thing led to another, basically through word of mouth: people seeing it and wanting. There was no such thing as advertising.”

In the late 1960s and 1970s, leaders in the Black Power and Black Arts movements were calling for self-determination within the Black community. Pan-Africanism was central to this movement. People of African descent, regardless of their nationality, were carving out uniquely Black spaces in language, art, music, and economics. This and other Black liberation movements renewed interest in supporting Black-owned businesses.

Into the 1990s, conferences and events like the Brooklyn-based African Street Festival were especially lucrative for creative entrepreneurs. Sin could make up to $10,000 in one weekend. “Many people owe their success to these events,” he shares. Some were able to establish a large enough customer base to open brick-and-mortar shops. Sin used these events to amass a mailing list of customers.

As they grew in popularity and scale, some public events were no longer accessible for emerging makers. By this time, Sin had started hosting private shows at galleries, stores, and hotels. These shows were more productive and allowed Sin to engage with his customers personally. He and his wife, Akosua Bandele, have built and maintained maker-customer relationships for decades, continuing through the pandemic lockdown with Facebook Live virtual exhibitions.

During an exhibition for Bandele’s hand-crafted jewelry, she stopped in the middle of showing a piece to greet an old friend who had joined the livestream. It was on full display: the life of a craft entrepreneur runs on relationships.

“I got to D.C. and connected with Dave Gilbert, who had a leather goods store,” Sin recalls warmly. “He was an excellent craftsperson. He kind of took pity on me. He said, ‘Marvin, have you ever heard of a sewing machine?’ I was trying to explain to him the authenticity of my sewing by hand and how that was important to my aesthetic. He ignored me and took a couple of my bags and had his staff sew the bags up. Overnight, my production increased from snail’s pace to rabbit’s pace. I had an inventory of products that I could sell.”

Establishing a means of production both refined Sin’s products and altered his clientele. “More sisters were buying the bags than brothers now. I was able to tap into that much larger universe of support and patronage.”

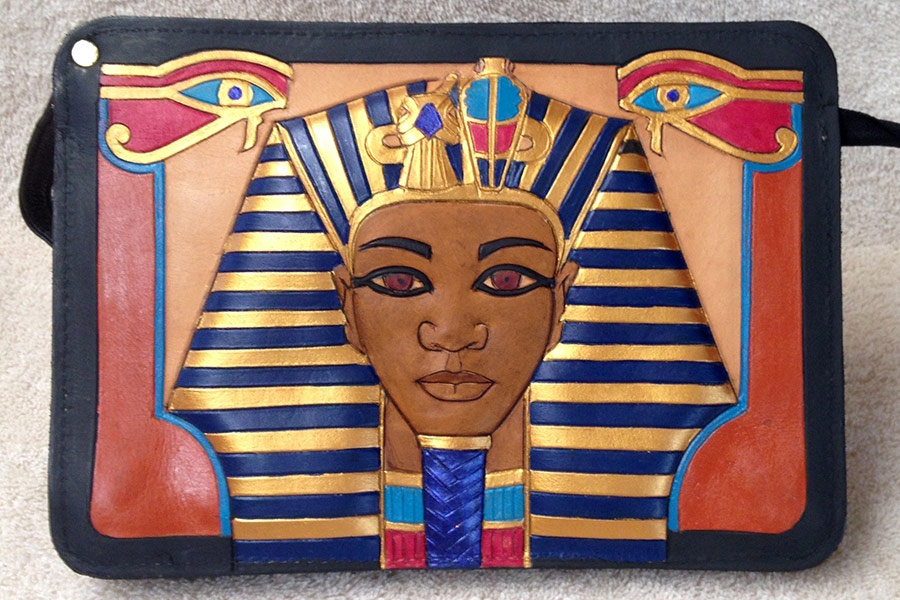

Throughout his career, Sin has centered Black life in his work. “Thematically, I’m dealing with Afrikan sculptures and Afrikan textile patterns from across the continent, African symbology, images of Black women in a range of cultural representations, abstract patterns, themes of nature—the things that I’m connected to.” In 2013, he was a featured artist in the Smithsonian Folklife Festival’s program on The Will to Adorn: African American Diversity, Style, and Identity.

Language as a Cultural Signifier

Some proponents of Pan-Africanism embrace alternative terminologies, naming conventions, and cultural practices to disconnect from the lasting legacies of slavery and colonialism. One example of this is the use of the letter K in place of C or Q in words relating to Black culture and geography (e.g. Akkra rather than Accra, or Kongo instead of Congo). Letters C and Q were introduced to written African languages by Dutch and English colonizers.

“I see myself as an Afrikan. I spell that with a K, not a C, because the African with a C could be a white South African, born in Africa. He can come to me and say, ‘You’re not African. I’m African.’ My Afrikan is conceptual. It’s theoretical. It is essentially the Pan-African idea that all people of Afrikan descent are connected, but it’s filtered through a cultural lens. I’ve always centered my creativity in and within Afrikan and Afrikan American aesthetics.”

Language as a Cultural Signifier

Some proponents of Pan-Africanism embrace alternative terminologies, naming conventions, and cultural practices to disconnect from the lasting legacies of slavery and colonialism. One example of this is the use of the letter K in place of C or Q in words relating to Black culture and geography (e.g. Akkra rather than Accra, or Kongo instead of Congo). Letters C and Q were introduced to written African languages by Dutch and English colonizers.

Along the arc of their careers, Sin and his friends have discussed whether they should create with a broader audience in mind. “We’ve had conversations about preferences in terms of whether it would be more economically feasible to move into other universes,” Sin begins. “It is important to me to reflect and represent who I am to the extent that I’m able to sustain myself doing that.

“I think that’s a mark or an accomplishment of great freedom that I wouldn’t be prepared or willing to exchange just for market access to another universe that is dubious.”

This choice is marked by experience. Early in his career, Sin met with the original owners of Coach in Greenwich Village. “This was when they were basically selling bags to New York hippies. Before they became this global brand, it was a family business, and they had a leather art collection,” he explains. “The wife contacted me—I don’t know how. I went down and brought some of my wall art. I was using the same images and mounting them on wood. I had a piece that I was selling regularly for $125, no problem. I showed it to her, and she thought it was too expensive. Meanwhile, I’m looking around, and I know they paid hundreds and thousands of dollars for these other pieces. But for me, okay, this was too much for them to pay.”

Personally, I’ve never sold a piece of art, so I don’t understand the slight that Sin describes here.

Not letting me miss it, he continues: “If you’re collecting art, you have an aesthetic appreciation. If I’m a leather art collector, and you bring me something I’ve never seen before, I’m going to want it if it’s not exorbitant. I want this in my collection, because I never know who you’re going to become ten to fifteen years down the road. I’m going to get you now when you’re affordable.” Sin attributes this undervaluation of his work to the implicit bias that can come with culture. “Art is a cultural matter. I think we delude ourselves to think that there is going to be a time in the future when the dominant culture is going to embrace us and celebrate us and recognize us on par with their brothers and sisters and cousins and nephews. That’s not going to happen, and it is because of culture.”

Sin’s relationships with other Black craftspeople yielded not only mutual support but new ways of approaching craft. The National Conference of Artists was a critical resource for meeting Black creatives from other cities, across ages and disciplines. Sin was part of a cohort of young designers working to sustain themselves through the design and sale of wearable art. This group, initially at the margins of the conference, became integral to the organization as they encouraged other makers to embrace entrepreneurship.

In 1988, a group of Washington, D.C.-based artists from this network started discussing ways they could collaborate and uplift Black art. “When we say Black art, we’re really talking about Black conscious art,” he explains. Black consciousness can be understood, in part, as a willingness to become aware of our heritage and to commit to uplifting Black communities for good. The next year, that group developed a set of guidelines they called the Golden Age of Black Art , or GABA, that grew out of this need to articulate a vision for Black people in the future.

GABA’s early calls to action, outlined in “The GABA Proclamation,” included “developing, exploring, and expressing their visions” as artists in all mediums and restructuring Black culture around its creative capacity. “The reality was that the future was not written,” Sin says. “But there are people who have drafts ready, and we recognize that if we don’t consciously design what our future is going to be, we will continually exist within the margins of somebody else’s design.” GABA has since extended into the twenty-first century, its members strengthening the organization’s guidelines with each iteration.

In the 2010s, GABA artists articulated that “GABA 2 should continue to identify and connect people and projects that use art as an instrument of spiritual, cultural, political, and economic development.” Sin shows us a model of this mission through the Garvey House.

Five years ago, Sin connected with a longtime friend and fellow crafts-based entrepreneur, Andrew Wilson, in New York City. Since then, the pair has established the Garvey House, a design and production workshop based in Kumasi, Ghana, for Sin’s wearable-art line, The Art of Leather. Last year, Sin recorded a YouTube video detailing the journey.

Over the course of eight month-long visits to Ghana, Sin and Wilson connected with the artists who produce Sin’s designs, the full-time attendant and groundskeeper for the workshop, a production manager, a logistics coordinator, and various other artists who have helped them acquire worktables and sewing machines and expand their network.

Sin and the Garvey House team, including students from the Centre for National Culture in Accra, paint, carve, and sculpt on the leather and assemble bags before shipping them to the United States for final sale. The team is also working to establish a local customer base. With each project, Sin transfers his knowledge into the fingertips of his young team and lays the framework for a kinship between Black Americans and Ghanaians. In his video, Sin imparts his desire to create “systems of design, distribution, and marketing that will be durable, sustainable, and scalable,” and that will have “a profound effect on providing on-the-ground economic development for people who are often ignored and overlooked.”

“We want to make a contribution to the continent so that our children and grandchildren will be welcomed here, and so that it will be sustainable,” he explains.

This humanistic approach relies on intercultural collaboration, appreciation, and understanding. To me, it seems that Sin and likeminded artists are developing a generative and ambitious system that breaks the extractive and exploitative practices associated with “fast fashion.” Their system runs parallel with mainstream production, intersecting at times, but always recognizes the way people work and what they need to live.

“What we would just spend on a Big Mac, in sub-Saharan Africa, is a meal for a family,” he says. “Anything is multiplied by its impact. Our mission at this point is to build bridges, just to establish relationships—no matter where we go.”

Sin hopes that the partnerships he’s building today will transcend national boundaries as well as generations. “No Ghanaian is ever going to look at me as a Ghanaian. They’re going to look at me as a Black American. But what they need to see is that I’m an American Afrikan, and they’re Ghanaian Afrikan. Let’s look beyond our colonization or our enslavement to see each other. What can we make of that beyond those artificial boundaries and borders?”

“That’s the importance of craft,” he concludes. “It is perhaps the last economic creative possibility for us to own and control an independent economic ecosystem. We have created and isolated a system of creativity where the creators connect directly to the consumer without any interference. The future is ours to design.”

Amber Long is an urban planner for the city of Rogers, Arkansas. She is also a freelance writer and a former writing intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.