What is the value of our family memories? Can they impact our daily lives, our communities, even the health of our nations? The work of Lest We Forget, a community-based, female-led cultural heritage project in the United Arab Emirates, helps answer these questions.

“The main thing is to not forget the memories, to not forget the values, to not forget the culture we were born into,” explained Esraa Al Kamali. She is one of four Emirati team members who discussed their work at the 2022 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C.

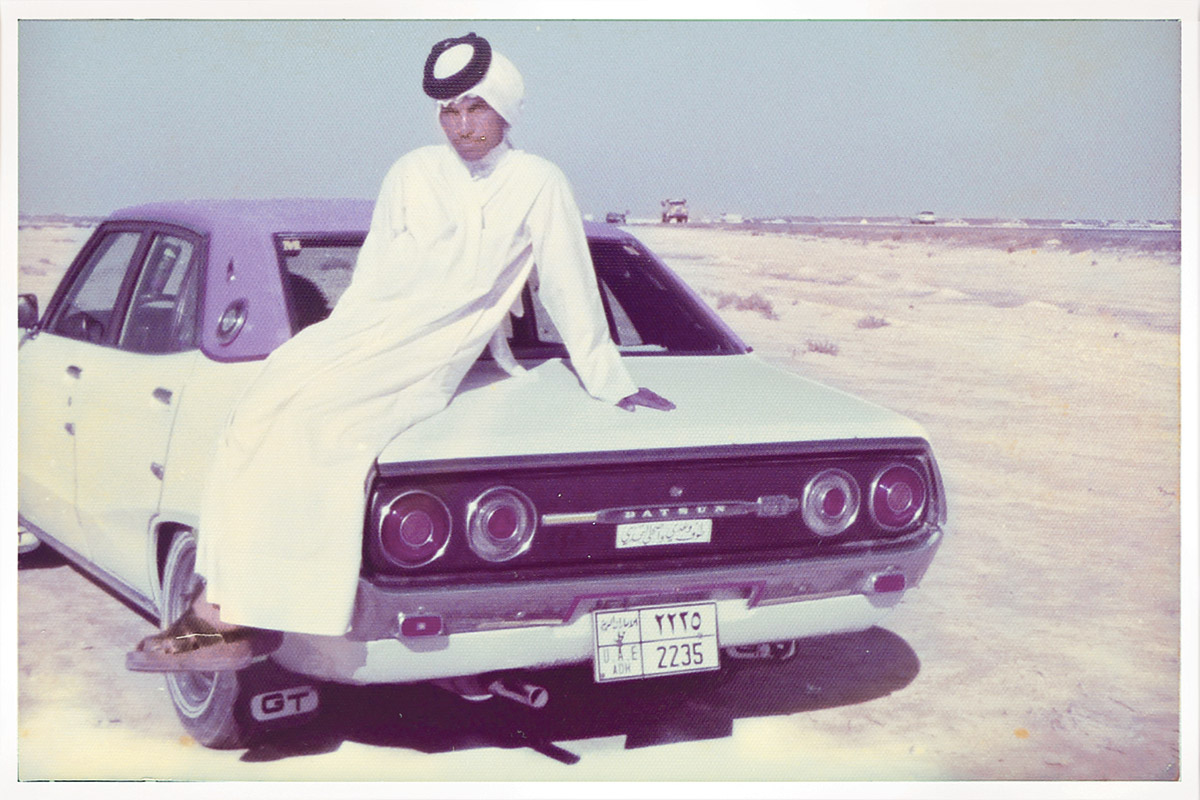

The Lest We Forget team primarily focuses on collecting community photographs, objects, and memories from the pre-digital era, which they worry are at the greatest risk of being forgotten. Over the years, they have carefully crafted a toolbox of artistic approaches to document, interpret, and share their findings with the public, whether through exhibitions, books, or merchandise inspired by the memories they uncover.

To understand the significance of this project for the Emirati people, it is important to recognize that family life in the UAE is a private place. Still, with consistency and patience, the team has earned the community’s trust. Many Emiratis have chosen to share their private lives, demonstrating support each time they recount a memory or lend a cherished family object.

“These families want to show people what their lives are like,” reflected Safiya Al Maskari, a team member, during the Festival panel.

Incredibly, Lest We Forget began as a class assignment. A decade ago, when Dr. Michele Bambling assigned a project about family snapshots and their associated memories at Zayed University women’s campus in Abu Dhabi, photographs of Emirati home life were rarely shared publicly. Since then, Lest We Forget researchers have built the project into a national initiative, opening the collection to other aspects of cultural memory including traditional garments, scent recipes, henna patterns, and jewelry.

Each shared story contributes to a meaningful collection of memories, reflections, and aspirations. Each is a unique thread waiting to be woven into the country’s rich cultural tapestry.

After the panel, the team explained to me how they think connecting with culture and heritage can help Emiratis better understand their modern identities. Their country has gone through rapid changes in the last fifty years that they think warrant reflection. “There were people of the desert, people of the sea, and people of the mountains, but now we’re all one,” explained Al Maskari.

The UAE is a young country, founded just fifty years ago when seven sheikhdoms reached an agreement to form a nation. “It’s important to keep the identity and culture of each region,” Al Kamali added. “These identities go back thousands of years!”

Between 1971 and 1972, a federation was established between the emirates Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm Al Quwain. Oil had been discovered in the Arabian Peninsula, and Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, then ruler of Abu Dhabi, began investing in infrastructure, especially roads, schools, and hospitals. The other rulers noticed his approach, and Sheikh Zayed helped facilitate the agreement that formed the new nation and the national Emirati identity.

The women of Lest We Forget revere “Baba (Father) Zayed” and embrace this change, but they also do not want Emiratis, especially the younger generation, to forget their ancestors. “If these memories are gone, that means that they won’t know where we came from, or how they were living,” explained Al Maskari. “If that part is gone, then the whole culture and the heritage would be gone as well.”

The past is also a mirror that can be used to reflect modern culture. Sarah Al Hosani, a project team member, wants Emiratis to notice what they see in this mirror of history, using this perspective to question “how culture has changed, how we are now, what type of traditions stayed but also changed with us.” Learning about the past can help families better understand how their experiences fit into the whole.

Historians might call this a “sense of history.” This phrase explains how people understand the past through the intersection of formal history written in books and what they gather from their personal, lived experiences, which includes memories passed down from elders. These memories can help us understand how we fit between past and future generations. In the words of historian David Glassberg, “a sense of history locates us in time” while helping us understand our place in society, “connecting our personal experiences and memories with those of a larger community, region, and nation.”

*****

In 2010, in the art department at Zayed University women’s campus, historical theory was not at the forefront of anyone’s mind. Michele Bambling, an American professor, was teaching a class called Curatorial Practices when she proposed a project about family photographs. Back then, it was just her gut feeling that this work was important.

I sat down with Bambling a few days after the panel. She had returned to the United States from the UAE as co-curator of the United Arab Emirates: Living Landscape | Living Memory program. We talked about her inspiration for that original assignment and her experiences growing the project into a national heritage initiative.

“I was trying to think of a way to engage young Emirati women in exploring their own culture, because most of the courses had been about the West and Western material culture,” Bambling explained. Eager to understand her new home, she consumed all the publications she could that covered the nation’s nascent years and its rapid modernization. She started noticing that almost all the photographs she could find from this period were taken by non-Emiratis, recorded “through the lens of people who had specific purposes, and those purposes were not to document Emirati home life or experiences.”

She wanted her students to look inward. She asked them if they were interested in learning how their own families had experienced this change by seeing it through “their cameras and perspectives and desires.”

First, Bambling had to convince the women that these photos had value—not just to their families but to their communities, maybe even their nation. “It took a long time for that connection to make sense to them.” They believed they should be learning about the “great photographers” of the world, not looking at whatever was stored in shoe boxes at their grandparents’ houses. After three months of waiting for a single photo to emerge, Bambling had almost given up.

But one day, she found a surprise on her desk. A student, who was a granddaughter of Sheikh Zayed, had brought in a family album. Typed on a label and glued to the cover were the words, “Lest We Forget: HE Sheikh Sultan bin Zayed Al Nyhan, Africa 1974.” Everyone was blown away. This vacation album contained never-before-seen photos of the sheikh’s private life. To describe this as unusual is a massive understatement. When the students went home, they told their parents what they saw. Bambling thinks the parents took the album as an endorsement because more photos soon emerged.

The following school year, more students requested she include the family photo project in the syllabus, hoping to expand on what the first group started. However, for reasons of privacy, the first class had established a pact that no one outside their group would see the photos. Bambling invited the original students back to meet with the new class, and the new students asked their predecessors for permission to view and add to the collection. Seven of the students agreed on the spot, and the eighth called Bambling three weeks later with a change of heart: “This should be for all the students,” she said.

Bambling may have introduced the project, but her Emirati students quickly molded it into their own. “When I took them to the library to study and research the history behind their family photographs, they were frustrated because there was very little research material,” Bambling recalled. Photographs like these had never been published. She was also teaching a drawing class that semester, so her students said, “Michele, you’re teaching us to think with our pencils, to communicate through visual language. Why do we have to go to the library? Why don’t we create an artists’ book and explore these photographs artistically?” This approach would define the project.

Ultimately, three classes banded together in an extended collaboration where they experimented with artistic methods for communicating and interpreting these photos and the memories connected to them. Lest We Forget’s current leadership team was part of this collaboration.

Together, they published the nation’s first book of Emirati family photographs called Lest We Forget: Emirati Family Photographs, 1950–1999.

“We used typewriters to hand-type all the stories, and in the process of hand-typing, the students slowed down and started asking questions about their current identities, and how things have changed in their own lives,” Bambling remembered. The students placed transparent sheets over the photographs and handwrote personal memories and reflections. The book came in a box as a nod to the shoe boxes that so often house family photos.

Although the words “Lest We Forget” were typed on Sheikh Zayed’s photo album, they derive from Englishman Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Recessional,” published in 1897 as an homage to God and country. When Bambling applied for a grant to fund the growing project, the committee expressed that the name should be changed because it was appropriative, or taken from something that didn’t belong to Emirati culture. They advised that if they changed the name, they would get the grant. When Bambling discussed this condition with her students, their response was a resounding no. “We’re co-opting that line because it came from our culture, because our sheikh had it on his album, and we responded to that,” they expressed. So they stuck with the name—and still got the grant.

Their first exhibition was a private opening at Zayed University held exclusively for students and their families. For the first time in the UAE, family photographs appeared outside the home in an exhibit, and, for the first time, photos of everyday people appeared side by side with high-level leaders like Sheikh Zayed. Everyone felt some trepidation about how the families would react, but the opening was a huge success, and more memories poured in.

Bambling recounts their enthusiasm: “‘Oh, my goodness, that’s my cousin! I was there too! I have that same backdrop in our family album!’ So the community started to speak.”

Eventually, this excitement reached the Salama Bint Hamdan Al Nahyan Foundation, a private, not-for-profit organization with a mission “to invest in the future of the United Arab Emirates by investing in its people.” Lest We Forget met the foundation’s art, culture, and heritage goals and was invited to become an archival initiative in 2013. It still operates as an independent initiative of the foundation today.

Bambling was offered the position of creative director to help grow the project from classroom to community. She hired a team of four former students, hoping that someday they would lead the project. After working together closely for six years, they officially took the reins in 2019.

*****

Although the scale has grown significantly, the project continues to honor its original spirit by valuing participant comfort beyond all else; anyone can change their mind about a contribution at any time. “The connections you build, it’s like a family,” explained Al Kamali. “They share their private life with us. We feel with them. We cried with them, and we laughed with them. I think that connection made them more approachable.”

The women see their gender as a benefit. Ayah Al Heera, a team member, described the relationship between the participant and the interviewer as much like that of grandparent and granddaughter. She thinks this rapport helps people feel comfortable and “open freely with everything.” Being millennials is also helpful, she explained. “We are kind of like the middle generation between two generations. We understand the old people, we understand the young people, and we kind of take the messages and deliver them. We’re a connection between them both.”

As a non-Emirati, Bambling understood her role on the project as reflective, able to call attention to cultural norms that a more habituated person might take for granted. “Because I wouldn’t know, the Emiratis would explain their culture.” Her prompting challenged students to articulate aspects of their lives they had never thought about before, which led them to ask their elders.

Ultimately, the Lest We Forget team feels that understanding the why behind their actions has helped them know themselves and their culture in a deeper way.

“Why do we still wear traditional clothes?” Al Heera posed during the panel. “When we listen to the grandparents and the stories behind it, we understand it. If you know the history, you will continue doing it. So you need to know the history behind everything—that’s very important.”

Each time the project reaches a new audience, collective enthusiasm grows. Bambling remembers how excited the public got in the early days to see intergenerational connections and similarities. “This linking between stories was very important.” She thinks this work helps build a collective memory.

Al Maskari recalled one of their early public exhibitions. “An older man came in and saw a picture of his friend, and he got jealous. He said, ‘Wait, how is this guy’s picture here? I’m going to bring my pictures tomorrow. Can you put us in the exhibition?’” This is how the collection grows, she chuckled. “It’s all word of mouth.”

The message of their work seems clear: if something is significant to culture, it should be remembered. Lest We Forget has now published six books that explore various aspects of Emirati identity, values, and traditions. Each features photographs, material culture, and oral histories.

For instance, “scent is a big part of our daily lives,” explained Al Hosani. “You will always smell something when you enter our houses, or even sometimes before entering the house. And this goes back in history, because scent is used to give messages, for example, to neighbors. If there is someone making coffee, that means he’s inviting the neighbors to come join them.” After a gathering, scent also plays a role as hosts burn incense to cleanse the smell of food from their guests’ clothes. “We will never allow them to leave unless they’re smelling good,” she explained.

Fresh henna had dried on Al Maskari’s skin. She raised her hands, revealing the design. The Bedouin woman (from a nomadic Arab tribe) who applied the henna, also a Festival participant, shared that this was the pattern she had worn on her wedding day many years ago. “She was reliving that memory,” Al Maskari said, smiling. “She was telling me her story about when she was a bride, and she was putting the pattern on me, and she was just so happy.” The intangible is just as essential to cultural memory.

Exploring family memories, regardless of their form, can pack a personal punch. Al Heera’s experience with her own family’s photographs demonstrates this strength. “I always had so many questions about family images, but never actually realized that I could ask.” When she went to art school and got an assignment about family photos, she realized that she could. Her father’s enthusiasm and openness surprised her. Typically quiet and calm, “he was very excited to see me wanting to know more about the culture and about the history of the family. I think this process grew that relationship between me and my father.”

The Lest We Forget team continues to inspire Emiratis to look inward. They figure the project will continue as long as the public finds value in looking.

Since this journey began, Al Maskari has realized her insatiable need to preach the importance of preserving family objects and memories. “Just keep it safe, even if you’re not sharing it with the wider community—just for you, just for your family.”

Each memory, each family photo, each handmade necklace or family scent is a valuable thread in the tapestry of Emirati cultural heritage. This cloth will continue to evolve. Each thread will help bind the whole.

Devinne Melecki is an intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a master of public policy with a graduate certificate in public history. She is interested in utilizing historical stories to inform present-day solutions to environmental and social issues. She is also passionate about homemade hot sauce.