A name matters. It is more than a combination of letters; it is an index of your life. A name is given by your family with great care and carries an emotional weight, a sense of belonging to your home. Your name represents your cultural heritage, embodies your life experience, and can reflect a personal sense of identity.

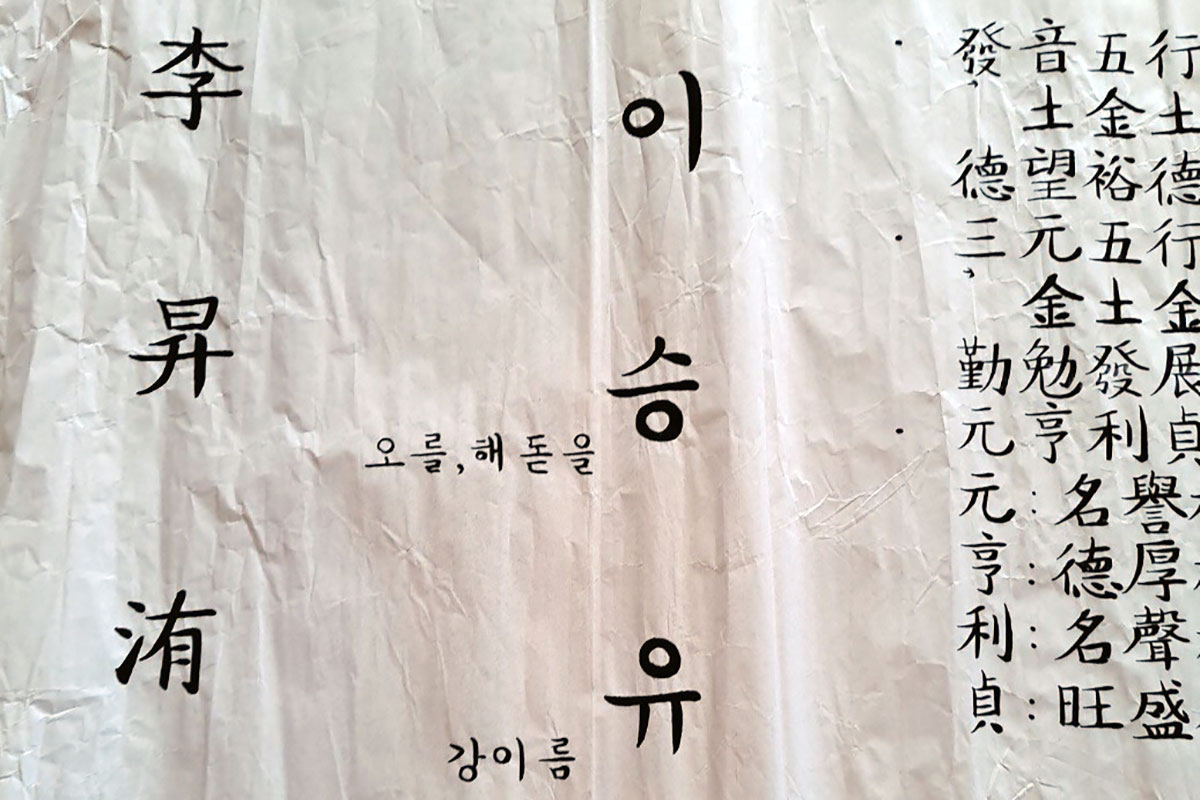

My name is Hyein. My parents named me according to Korean tradition where each syllable carries a meaning: hye stands for wisdom and in stands for benevolence, conveying my father’s aspirations for me. In other words, when I was born, these values, attitudes, and directions were assigned to me to guide my life’s choices and decisions. All of this embedded in my name.

Some people have more than one name. Even if they are not K-pop idols using stage names for marketing purposes or artists exploring new personas, we can easily find people with two or more names: Koreans living in the United States.

Although I’ve been identified as Hyein for my entire life in Korea, I started going by Hazel in the United States, where I studied abroad. I truly loved having a new name. But one day, as I left my campus in Santa Barbara, I began to wonder: after I leave behind the azure skies of California and return to Korea, how would I be remembered by the friends I made here—as Hyein or Hazel?

An old East Asian proverb popped into my head: “A tiger dies and leaves its skin, and a man dies and leaves his name.” When I die, which name will I leave behind?

In Korean culture, names are believed to affect one’s destiny. What happens if you are “owned” by two names?

I made a plan to interview my Korean friends with multiple names to see what they thought.

Unwelcome Names

I’ve lived in the United States for several months now but haven’t gotten used to the American approach to meeting new friends. For me, it is a little weird that people try to make conversation by first asking my name. In Korea, the name is considered so private that nobody shares their name with a stranger.

In the United States, cafes deliver my coffee by calling my name; even in some clothing stores, I am asked my name when using the fitting room. No one ever mispronounces or asks me how to spell “Hazel.” When I visited souvenir shops in New York, I was surprised to find racks of magnets bearing almost all my friends’ Western names.

Names are primarily associated with a sense of who you are; nevertheless, it seemed there are only a few sorts of “American” names. The United States is a nation of immigrants, but some immigrants are viewed as more foreign than others. Perhaps some believe their names are not welcomed and should be made “easier.”

My friend Jiyoung is one of a handful of Korean students I know at an American university who doesn’t go by a Western name. She often tells me the various ways her professors and supervisors mispronounce her name. Then we laugh together, sarcastically saying, “At least they try.” But Jiyoung has decided to go by a Western name should she return to the United States.

“I didn’t want to rename myself just for the sake of English-speaking people, but at work, my bosses couldn’t call me by my name,” she said. This experience made her feel as if she didn’t matter as a unique individual, that she was merely a worker filling a labor need.

But people remember Timothée Chalamet. Why not Jiyoung?

Some Asian people feel they have little choice but to “whitewash” their names. A 2017 study at Ryerson University and the University of Toronto revealed that job candidates with Asian-sounding names were twenty-eight percent less likely to get an interview than those with Western-sounding names. Some theorists see the adoption of an anglicized name as Americanizing, but the question of who is perceived as a “real” American remains.

Jisoo, who goes by the name River in the United States, expressed her reasons for the change. “I didn’t want to let people looking over a list guess that I’m an Asian girl and stereotype me based solely on my name.”

By adopting a Western name, she aimed to avoid being labeled a peripheral Asian or Korean girl. She had concerns that her “Asianness” would overwhelm her sense of self. Jisoo’s experience highlights how, for some, an anglicized name functions as a strategy to protect their individuality. Intentionally obscuring our ethnicity—in a sense, distancing ourselves from our culture—keeps us from projecting foreignness to those who might “other” us.

Despite the long history of Asian immigration to the United States, dating back to 1763 and reaching a turning point with the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, we live in a society where our names still make people anxious. Sojin Kim, a curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage whose work often focuses on Asian American immigration and identity, shared her story as a second-generation American who stuck to her Korean name.

When ordering from fast-food restaurants, she said, “Sometimes, I just say Kim or give them a friend’s name, but sometimes I want to force the point and make them write my name out and pronounce it. Why not? Then when I hear them calling names and I see them pause, I usually know it’s for me.”

Although Sojin is pronounced in English exactly like it’s spelled, she often finds people “sort of freak out” and have “funny anxiety”—though she understands as pronunciation rules are different in different languages.

How We Got Our Names

My interviews about names unveiled fascinating narratives about the strong societal and internal pressure to Westernize. My favorite naming story came from a Korean American friend of a friend, who chose her English name based on a character in SpongeBob SquarePants, Princess Mindy—a childhood favorite.

In many instances, Asian parents give their children two names with the hopes they will maintain a connection with their ethnic identity while successfully chasing the American dream. Jasmine’s story stood out to me. Her grandfather first named her Jaehui, and her father wanted to give her a Western-sounding name as well—hence Jasmine, similar in sound to Jaehui.

When Korean students decide to study in the United States, one of their biggest shared concerns is which name to use. Moving to another country provides an opportunity for a new start, to establish a new identity, and a new name maximizes the anticipation of it. But the adoption of a new name doesn’t just happen overnight. It’s a process of self-defining that needs thorough consideration, which strengthens the resolution for a new life.

Eunju frequently changes her name to create turning points in her life. After meticulous deliberation, she has settled on the name Juniper, because ju in Korean depicts a tree trunk. Jisoo took five months to choose the name River; a Google search led her to the name, which she thought had the vibe of a trendy boy band frontman. Another friend, Hojeong, adopted the name Ava, inspired by the protagonist of her favorite comedy drama. She hoped her life in the United States would be as witty and fun as Ava’s on TV.

Within my Korean student friend group, we had to practice calling each other by our American names. Today, Eunju/Juniper takes pictures wherever she finds her name and collects every juniper berry hand cream and moisturizing lotion she finds. I/Hazel am obsessed with ordering hazelnut coffee or gelato.

A Balancing Act

Though we sometimes have to sacrifice our names, we define ourselves in various ways, navigating our complex relationship with multiple names. Having a Western name while retaining the ethnic name involves negotiating multiple identities.

“I am Jaehui at home and in Korean language school,” Jasmine tells me. She keeps Jaehui as a middle name. “So Jaehui represents a respectful, meek, docile part of me, like a good student. But with my friends, when I go by Jasmine, obviously I feel like using more slang—do you know about code-switching? In that sense, I feel that strongly.”

Code-switching is a sociolinguistic phenomenon in which speakers cross between two or more languages. A survival tactic, code-switching allows minority groups to assimilate into the predominant culture. This can help them avoid exclusion from entrenched power groups, while allowing them to construct and maintain a sense of cultural identity.

My Korean American friend Eunsae used the name Kaitlyn while at a predominantly white high school. But in college, on a campus with a high percentage of Asian students, she embraced her Korean name.

“My English name affects my fitting into society here because it’s a common name,” she said. “Taking it was a rite of passage. But if I didn’t have my Korean name, I would feel disconnected from my culture. For me, being called Eunsae just feels so natural, a constant reminder that I am Korean.”

The code-switching feature of two names illustrates the transnational diasporic identities of Korean Americans. Eunsae can syncretize her Korean heritage with American identity through her two names. These flexible identities are not fragmented but are being integrated. The names made it feasible to assert the United States as a home without giving up their Koreanness.

In the Third Space

Sometimes people ask me if Hazel is my “real” name. But I think our naming practices are beyond issues of authenticity. Adopting an anglicized name is more than an imitation of white norms. Rather, multiple names create a new space where the blending and reprocessing of two cultures takes place. It diversifies the ways we relate to the world.

Of course, English names do not alleviate all problems of “foreignness.” As Sojin said, “In many cases, just by sight, people who are not Asians, who are Americans, will assume we’re foreign no matter what our names are.” Even if we Westernize our names, we cannot equate ourselves with white dominance. Nonetheless, the differences that cannot be so easily identified are more important.

Postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha proposes the concept of the “Third Space,” a distinct hybrid identity evolved from cultural negotiation, producing something recognizable and new that entertains and combines differences.

This reminds me of something I heard from the 2023 White House Forum on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Artist and entrepreneur Eric Nam’s inspiring speech on the meaning of being Korean American especially resonated with me: “We can sit at the intersection of an incredibly globalized world.” Arriving at the crossroads between the Americas and Asia, we of two names live in a Third Space where our worlds overlap, mix, and permeate each other. We can experiment with boundary-crossing.

Within Los Angeles’ K-town, you’ll find some psychic astrology places that offer traditional naming services. Interestingly, they provide their clients with not only Korean names but also Westernized names based on the ancient East Asian zodiacal theory. Considering that a name symbolizes, represents, and stands in for its bearer, the endeavor of balancing fluid identities lies in this reproduction of naming practice in this faraway land from Korea.

Again, names matter. For some, only an Asian name will do.

“Having the name is a very important piece that I hold onto, which connects me strongly to being able to assert that I am Korean American,” Sojin said. “I have spent very little time in Korea. I have visited the country only twice in my life, I don’t speak the language, and I don’t cook Korean food all that well. But still, I have the name.”

*****

Names illustrate the adaptability of the self. At the intersection of fluid identities, our names are bridges that can be crossed. Living within American culture, I feel that my new Western name reflects the autonomous version of me that I cultivated, while Hyein embodies the version of me that exists within a social network. It always reminds me of my supportive family and the people surrounding me. In contrast, Hazel freed me from my comfort zone. It manifests the bravest version of myself, who crossed the bridge between my home country and a whole new world.

Once I am done with my studies in the United States and my feet touch ground in Korea, I might no longer be known as Hazel; it will be time to come back to Hyein. Still, I’ll wonder if another day will arise when I can be called Hazel again. But Hazel will forever remain a significant part of me. That name will remind me of my days in the United States where I embraced independence and fearlessness—and dreamed.

So, what’s in your name? I recall Sojin’s insightful words: “The interesting thing about a name is that it can precede you. It also is you.” However, the name can be changed. The name can be multiple. Perhaps life is a profound journey to integrate all our names.

Hyein (Hazel) Lee is a former writing intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a student at Yonsei University, majoring in cultural anthropology. She also studied abroad as an exchange student at the University of California, Santa Barbara.