Although I grew up in Texas, I didn’t see myself as someone engrained in gun culture. Still, I loved watching shoot-outs in action movies and was happy firing off rounds as James Bond on Nintendo 64. In the backyard, I imagined ordinary tree limbs into guns. Isn’t that just what kids do—or used to do?

My parents never owned guns, nor did anyone on my father’s side. My mother’s family were ranchers and often hunted for food, as the grocery store was a considerable drive away. I never thought twice about it; it was a normal part of existence.

Today, guns are a controversial subject, especially in these times of heavy political discourse over the Second Amendment. To me, these discussions teach an important lesson: we should keep an open ear to voices we might not always agree with.

After I read a bit on “gun culture,” I realized it plays a major role in my life.

I asked my relatives—all gun owners—for their perspectives, whether they got into shooting for hunting, protection, or recreation. Those I questioned live across cities, suburbs, and rural communities. The result is a reflection on modern Texas gun culture through the eyes of my family, about how guns have affected our lives, and why many of us place such value on them.

I spent my first ten years of life in Austin, Texas, the city we call the “Live Music Capital of the World.” In 2003, we moved slightly north to suburban Pflugerville.

My family regularly took trips. My grandparents’ ranch, located about an hour and a half south of San Antonio, was a complete contrast to where I grew up. There were no buildings. The only sound came from cicadas and the whistling wind. In the blistering Texas heat, summers felt like a desert. I shot my first gun there at the age of nine or ten.

Truth be told, I felt intimidated by the whole idea, but it seemed a rite of passage that every young man goes through. I aimed a shotgun out toward the target. I remember the recoil of the slug round expelled from the 12-gauge, as it knocked me to the ground.

My grandfather sees a gun as a tool to put food on the table and handle ranch emergencies. Douglas Taylor has spent thirty years working his ranch in the dry heat of south Texas and owns enough stories to fill several books. A tall, stoic man, he answered my questions in a relaxed manner, but sat with his back straight.

“We were raised a hunting family. We always hunted deer, we hunted quail, anything we needed to have,” he explained. “You had a shotgun or a .22 to kill a rattlesnake if he got around the house. Once in a while, you’d have a mad coyote, and you had to shoot him.”

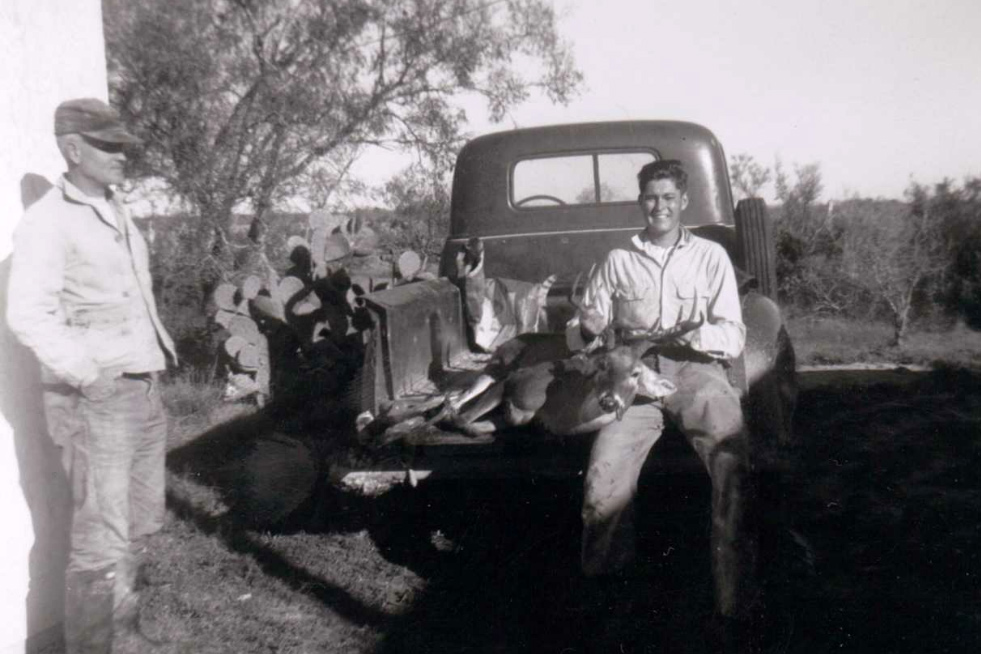

I think back to some early mornings spent sitting in a deer blind with my uncle waiting for the right buck to line up in the crosshairs of his riflescope, or in the bed of my grandpa’s pickup, shotguns aimed at quail. My uncle would clean an animal and prepare it for dinner the same night. We froze the rest to take back to Austin, which was appreciated as we were not well off at the time.

My grandpa was only seven when his father and grandfather taught him to shoot. He was introduced to guns in the same way he introduces young people to them today: “You point the gun at the ground, or you point it up in the air. All guns are loaded, regardless, and you treat them as if they’re loaded.”

Guns were always a big part of his life. He attended high school in the early 1950s in Alice, Texas. He recalled peers leaving guns in their trucks: “That was just the culture. If you were driving a pickup, you had a .30-.30 in your head rack. That was it.”

My grandfather joined the military in 1955, and Uncle Sam taught him to shoot a variety of weapons, including .50 caliber machine guns, M1 rifles, carbines, grease guns (aka the M3 submachine gun), and anti-aircraft weaponry.

Before returning to the family ranch he would forever call home, he raised a family in Corpus Christi—without any guns.

“We never thought anything about keeping them for safety, because we had no problems like that,” he explained. “I didn’t have any use for guns in Corpus Christi. You’re in the middle of the city; you can’t shoot nothing.”

On the ranch, things were different. He told me that he would have no idea what his life would be like without them. “It means I can provide food for myself and my family. It means I can defend my homestead if I have to. I have never had to do that, but I’m ready in case I ever do.”

The views of two cousins, Mike and Josh Wilmot, reinforced the idea that urban gun owners keep their arms primarily for home or personal defense.

“If I saw somebody walking downstairs in my house, I’m not going to run at them with a bat or a knife,” Mike began. “If they run at me, I would rather have something a little bit more powerful, something I can knock them down from a distance with.”

Mike studies criminal justice and plans to become a police officer. At the time of our interview, he lived in Leander, a quiet town north of Austin. He spoke confidently, displaying a great familiarity with guns. He owns several and fired his first shot at the age of twelve.

He identifies his uncle Larry as an exceptionally disciplined gun owner. Larry would take Mike shooting and reloaded his own ammunition by refilling spent shell casings. When he passed away, he left Mike guns he had owned and impeccably maintained.

“Shooting his guns, I feel connected with him in a special way,” Mike said. “He made some of those himself, customized them, then he left them to me. I feel blessed that he would leave me those. So, every time I shoot them, I think of him. Every time I clean them, I think of him, what he would do and how he would do it.”

From Mike, I learned that gun ownership can strengthen family and generational ties.

Over time, I’ve gained experience handling guns at shooting ranges. Though firing at targets may sound repetitive, I feel something special—sending ammunition down range, the power released as each round escapes its chamber, and the gratification in hitting the target. Mike described it in a visceral way: “The kind of explosions, the way the gunpowder smells, just kind of grabs ahold of you, and excites you. It’s something that you know you want to get good at.”

His cousin Josh, a recent college graduate, was also raised in the urban culture of Austin.

“I guess the main thing is that people that live in the city aren’t used to surviving off the land,” Josh said. “They’re not accustomed to thinking about guns like that.”

Josh doesn’t have a whole collection as Mike does, nor does he often practice at a gun range. He doesn’t fear for his safety, but he still feels it’s better to own a gun and not need it than to need one and not have it.

He was roughly thirteen when he shot his first gun, though it wasn’t his first experience with one. “When I was younger, when I was walking my dog, I had a bunch of guys riding around in a Lincoln, and they pointed a gun at me.” Josh later moved to McAllen, Texas, a stone’s throw from the Mexican border. “People kind of have this idea it’s lawless and that it’s crazy [in McAllen], but there is a lot of police, and a lot of security. I feel like it doesn’t really matter where I’m at. I feel like just having the gun as protection anywhere is important to me.”

Josh doesn’t worry about running into criminal activity, but he does take preventative measures for his safety and well-being. “I try and stay out of places that are dangerous or situations that are dangerous.” He believes that all law-abiding citizens have a right to personal protection. “I think whether you’re protecting yourself, or just want to exercise your right, people should be more than welcome to do so.”

I was reminded that my grandfather never saw fit to own guns in the city, but living in the country was different. There, he keeps them handy in case of a home invasion. Law enforcement isn’t quickly available in rural communities. He keeps a gun on his hip while moving about his ranch. “The only time I ever have security, if I live out here, is to carry one on my waist. That’s the only security I got.”

Gun culture is deeply rooted in my family, whether for hunting, protection, or recreation. It is a culture I now recognize as my own. My family has attached traditional values to guns and passed them down from one generation to the next, and I honor that. Yet, my relatives understand there are thought-provoking arguments on both sides of the gun control discussion, and realize that any dialogue we open on a divisive topic such as guns is a vital one.

“It’s going to be like any relationship,” Mike said. “It’s going to be a give-and-take kind of thing. You’re going to have to trust people.”

Trusting people means sitting down to listen—that’s the biggest thing I’ve learned in sitting down with my family. Disagreements can be hashed out. Agreements can be reached. If we trust each other enough to talk about guns, we can reach a common ground that respects both our individual freedoms and our safety.

Bryan Wilmot is a video production intern with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a recent graduate of Texas State University.