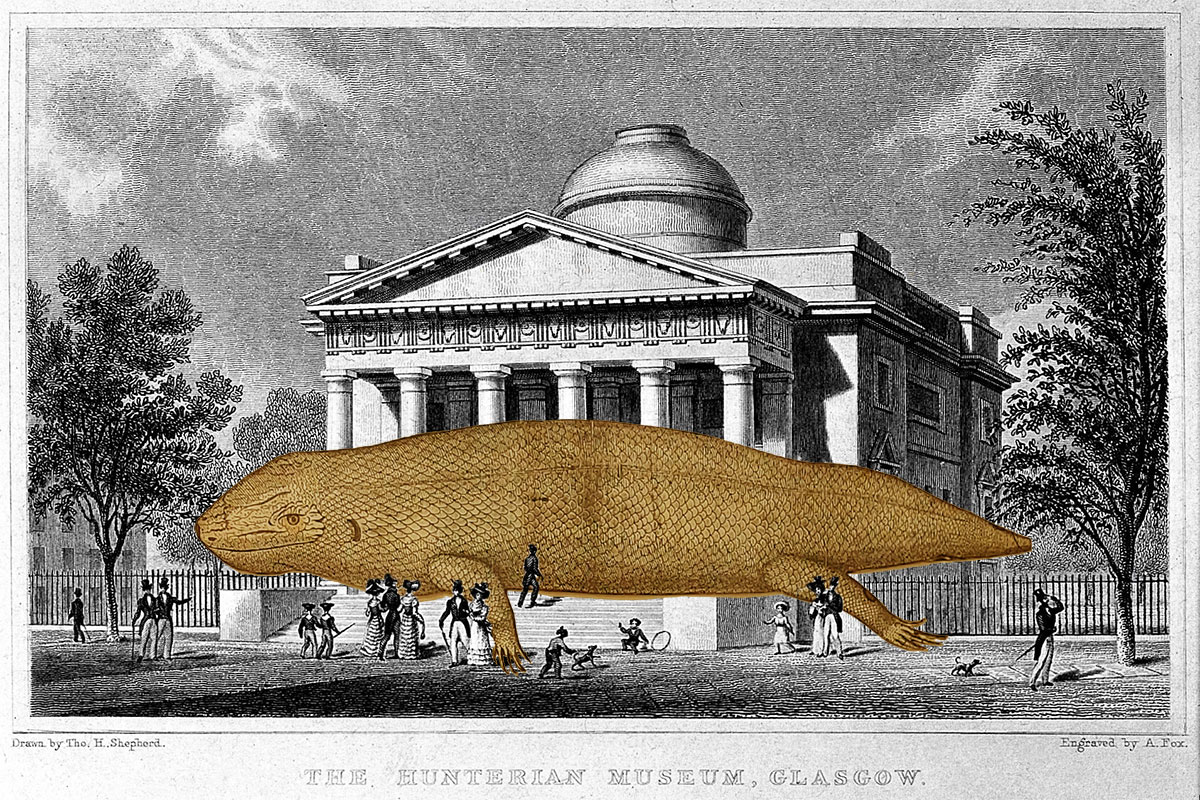

The Hunterian Museum is situated just inside the University of Glasgow, which sits atop a hill overlooking the city. Walking up to the museum, a grand staircase leads to a pair of large wooden doors. Inside, you’ll find the familiar feel of an encyclopedic museum. Shelved bones and objects suspended in mysterious, fluid-filled jars cover the walls. There are taxidermized animals, historical cultural objects from many parts of the world, and various anatomical parts. It’s an intriguing place to spur the city’s curiosity.

Until recently, in an exhibition just down the way from the entrance, a peculiar specimen rested on a bright orange shelf. It was easy to miss. But there, suspended in clear fluid, was a Jamaican giant galliwasp, twisted and warped. This lizard specimen became an important touchstone for Scotland’s involvement in the repatriation, or return, of museum objects back to their place of origin.

Each case in the exhibition Curating Discomfort contains objects from significant collectors of the museum. Contextual panels describe how these donated collections arrived at the museum; they name the collectors and the ways they may have benefited from these transactions. Many profited from the circumstances of the time, whether they collected directly from colonized countries or purchased objects with money made through colonial violence. Curating Discomfort is a new kind of museum exhibition, one the museum calls an “intervention,” a groundbreaking way to acknowledge such unethical practices that were once standard.

In museums, text panels most often tell a surface-level story. They date and describe an object, where it was found, but rarely examine the motivations of the collector. In fact, most museums in neighboring England seem to sugarcoat an object’s backstory, refusing to examine the dark truth of their colonial histories.

The staff of the Hunterian is working to pull back the curtain on its collection and push Scotland to the forefront of the repatriation movement.

The Hunterian and Its Galliwasp

I met Steph Scholten, the director of the Hunterian, on a rainy day in March, as we sat amid the museum’s collection. Scholten came to the role in 2017 and, these days, is deeply entrenched in the conversations surrounding the movement.

Repatriation strategies involve a lot of gray areas. Often, there aren’t enough frameworks and rules put in place, and cases are left to the discretion of individual collectors or museums. This leaves a lot of room for museums to make decisions based on what they think is best, which may not be the just solution. For example, museums may raise concerns about whether the recipients can correctly store the object in question, as justification for not returning it. For Scholten, it isn’t the place of museums to stipulate how a community should present an object once it’s returned to them.

“The thing is, for a museum, if the outcome of the process is that some things are not rightfully yours or shouldn't be yours, it’s not like ‘Okay, first, I steal your stuff, and now I'm going to tell you what to do with it.’”

That’s when Scholten brought up the Jamaican giant galliwasp. Celestes occiduus was a large, brightly colored species of lizard endemic to Jamaica and ubiquitous in Jamaican folklore. Its extinction was the result of colonization fueled by slavery. The British produced sugar on plantations, which encouraged a rat infestation, which owners solved by introducing a new species to the island: the mongoose. While the rat problem was solved, the predatorial mongoose wiped out the giant galliwasp and at least four other species.

While exact details surrounding the procurement of the galliwasp specimen are unknown, the bottom line is that the Hunterian obtained the specimen as a direct result of this colonial power dynamic, a situation Western collectors and scientists exploited for centuries to expand their museum collections.

The specimen’s journey home began in April 2022. It was then that Mike Rutherford, head of the Hunterian’s zoology department, elected to look further into the lizard on the shelf. He noted its accession year, 1889, and a lack of information concerning its collection. The echoes of colonial history concerned him—as did the number of specimens available for study in Jamaica.

“My research seemed to suggest that although there were other specimens in collections in the USA and Europe, there were no known examples in Jamaica itself,” Rutherford said.

He reached out to a curator at the University of West Indies Museum, Dr. Shani Roper, asking if UWI had any interest in the specimen. From there, things quickly took flight. After a series of meetings, they decided that UWI and Institute of Jamaica representatives would fly to Scotland and retrieve the specimen.

It may not seem that the return of a specimen of extinct lizard is a significant event, but when the Hunterian did so in April 2024, it would mean more to the people of the island than was immediately apparent. It also marked a new chapter in the repatriation movement, as previously, museums had only considered repatriating manmade objects—not natural history specimens.

So, Why Scotland?

The museums of Glasgow were pioneers of museum returns in the UK, entering the repatriation movement in the early 1990s, twenty-five years before other European museums. In the United States, the Smithsonian began repatriating objects in the late 1980s, which led to establishing the Native American Repatriation Review Committee in 1990 and what is now known as the Repatriation Office.

In 1992, a Native American visitor to Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Museum and Gallery recognized the historical and spiritual significance of a leather shirt on display. It was a Ghost Dance Shirt that would have been worn for protection during the Battle of Wounded Knee and was likely stolen as a souvenir from the body of a fallen warrior. The visitor reached out to Lakota Sioux tribal leaders in South Dakota. That same year, they made a written request for the shirt’s return. After six years of consultations and collaborative meetings, the priceless object was returned. It was the first repatriation from Europe to a Native American tribe.

Another example comes from October 2021, when the University of Aberdeen in northeast Scotland returned a Benin bronze depicting an Oba, or king, looted by British soldiers during the punitive expedition of 1897. In a statement, the university described the looting as one of “the most notorious examples of the pillaging of cultural treasures associated with nineteenth century colonial expansion.”

But what makes Scotland’s attitudes to repatriation so different from many other countries with colonial legacies like England, home to the world’s largest collection of Benin bronzes? The question is complex; what it might come down to is culture and circumstance. Core to the issue is the dated concept of the “Universal Museum,” a colonial idea of bringing as many of the world’s objects as possible under one roof for the benefit of visitors.

National institutions like the British Museum in London fear that if they return one object, their whole collection will go with it.

“I think that this fear indicates that the British Museum is aware of how much was taken,” explains Dr. Christa Roodt, a professor of art law and ethics at the University of Glasgow.

Roodt also spoke to the stark difference between the legislation in the two countries. “The legislation doesn’t allow for discretion in England, or what discretion there is is limited. In Scotland, you have much broader discretion.” This refers to the laws put in place in each country that control whether a public museum can deaccession objects from their collection.

Deaccession is the process through which a museum removes an object from its collection. In many countries and many museums, the laws and rules surrounding this can be strict and difficult to get around, as laws were made to make it impossible in some cases for a museum to lose its collections. It is important to note that in the UK, such laws that govern university museums are not so strict. This allows museums like the Hunterian more leeway in the complicated return process.

When asked about Scotland’s relationship with colonialism, Scholten called Scotland “an interesting case.” Having been colonized by the English in the 1700s, the country perhaps understands how it feels to have its culture and wealth stripped under forced assimilation. England thrust Protestantism on the Scots, forced many off their land, and overwhelmed the Scottish Highlanders in the pivotal Battle of Culloden.

“Which is why, traditionally, there’s that rhetoric around oppression of the Scottish by the English,” Scholten explained.

But that doesn’t mean the Scottish didn’t try their own hand. “Poor Scots were recruited into really poor working environments, but at the same time, as soon as they could, Scots became such an active actor in the whole empire project,” Scholten continued. Many Scottish citizens made their fortunes off the cotton industry, making cloth from cotton that was obtained from cotton plantations in the United States—an industry built off the work of enslaved Africans. So, in turn, many Scots, directly or indirectly, made their wealth from colonial violence.

Scholten wonders whether knowing both sides of colonial oppression made repatriation less challenging in Scotland.

Righting Wrongs

In discussing the situation of the giant galliwasp, Scholten touched upon an important aspect, rarely highlighted: repatriation is not just about returning things because you have to. It is about goodwill and collaboration between countries and communities.

“Working with people from recipient communities is a great way of starting to understand how important and sometimes urgent this is, how it’s not abstract,” he says. “It’s the right thing, and it’s the ethical thing. But it’s vital to both understand the level of trauma, or ongoing trauma, that keeping things in our stores causes, as well as understanding spiritual connections in ways that are way beyond me.”

At the 2024 Repatriation in Scotland conference in Glasgow, the galliwasp return took center stage, with Dr. Shani Roper and Dr. Elizabeth Morrison highlighting the importance of the case. Repatriations are not for show, Roper stressed; rather, they can help heal, even rebuild the culture of places and people.

The Jamaican giant galliwasp is an integral part of Jamaica’s cultural heritage. Stories of these creatures have been passed down in oral histories and folktales for generations. In Jamaican Voodoo belief, galliwasps were venomous—though we know today that they were not—and if one bit you, you would have to race to a body of water and reach it before the lizard. If it reaches the water first, you die. By reviving these stories and spiritual beliefs, the specimen’s return helps preserve Jamaica’s folklore.

The return of the galliwasp also makes its study easier for Jamaican researchers. “The Jamaican giant galliwasp has been extinct since the 1840s,” Roper says. “Its return not only completes the national collection but provides young scientists with access to a specimen that will enhance research. Already its return has stimulated significant local and scientific interest.”

Yet, repatriations like these don’t come without costs and challenges for the recipient communities.

“Everything costs money,” Roper says, “including the very act of returning a specimen, but there are other issues such as policies to inform the process and protect the items for return, infrastructure to house and specialists to care for items, especially if it’s to be placed in a museum.” This process can be extremely complicated and expensive. “For us, it required pushing through the necessary paperwork as it relates to conventions associated with the illicit trafficking of endangered species, import licenses since we were walking the specimen back into Jamaica, plus basic logistics at the point of arrival into the country.”

Before this return, Jamaican scientists would have to visit Europe to see the galliwasp, forcing the formerly colonized to visit the colonizer.

At the repatriation conference, Roper remarked on an important point: colonial countries often hold more in their archives about former colonies than the former colony holds for itself. This dynamic perpetuates colonial violence, gatekeeping another country’s history and cultural heritage, which can have detrimental consequences to the development of scholarly research and understanding of their own culture. She maintained that it would never have occurred to them to ask Glasgow if they had a galliwasp. If Rutherford hadn’t reached out proactively, a return like this would never have been possible.

As we chatted at the Hunterian, Scholten drove home a final point: “Cases like the galliwasp make clear that repatriation is not just about colonial loot. They show that a lot of repatriation is about other things, things that are not contested or not stolen, but actually would support a cultural regeneration.”

Repatriation Is Human

Coming to terms with how objects enter a museum—and understanding the legacy of colonial violence that is often perpetuated by keeping them—is something that comes down to empathy. Roodt highlighted that, in fact, repatriation is not a new concept at all.

“I’ve studied it for more than twenty-five years. So it’s not a fashionable thing or a woke thing or a recent thing,” Roodt says. “It’s not a trend started last weekend. And so my viewpoints are not political. They’re not inspired by or underpinned by politics. I think a lot of credit is due to the way the institutions work.

“There are a lot of ongoing lively conversations among the university museums,” she continued. “They are in touch and very interested in fine-tuning, always talking to one another about their practice. It’s like a big community of like-minded people.”

The future of repatriation is one that many are hopeful for.

“National museums, Glasgow museums, Aberdeen, ourselves, Edinburgh—we’re all kind of working well together,” Scholten says. He looks toward the future of repatriation in Scotland and the progress that is happening right now. “We’ve been working on a project called Reveal and Connect, which is an inventory of African Caribbean collections in Scotch museums.” He is optimistic that a tool like this could change repatriations, making it much easier for groups to know where their objects are.

“So if anybody wants to know, ‘what is there?’ they don’t have to ask fifty museums, but they can just filter this report,” Scholten says. Unfortunately, today, the onus is often on recipient groups to discover and know where their cultural objects may reside.

The work currently being done in Scotland makes it a beacon for the future of the repatriation movement, and museums like the Hunterian continue to charge forward, make new changes, and build solid relationships, while acknowledging the negative effects of a colonial past. The spark emanating from the Hunterian and other university museums worldwide may be the key to advancing repatriation. Scotland can be proud to have been at the genesis of this movement and to be continuing its advancement today.

Juliette Murphy is a former writing intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She recently received a master’s degree from the University of Glasgow in Scotland, where she studied collection practices, cultural heritage, and provenance research.