One day in November 2020, I got a surprise visit from my grandmother, Doris Marion. It had been a couple of years since I had last seen her in person, and it had been nearly eight months since she had passed away at the age of ninety-one. But when I found an old potato salad recipe of hers lying in my mailbox, she appeared before me like there was no time or space between us.

Peering at the slip of paper, I recognized her precise, cursive handwriting. When I read her cooking instructions, I remembered the many days I had spent with her in her kitchen when I was a child. For reasons I can’t quite account for, I could also very vividly taste the honey wheat loaf we made together one summer in the early ’90s when she bought a bread machine. I looked back at the card that had carried my grandmother’s recipe, and I read its message. My mother-in-law had very kindly sent it to me, as she knew that this would be my first Christmas without my grandmother. Because of this kindness, I saw Doris Marion again for just longer than a heartbeat.

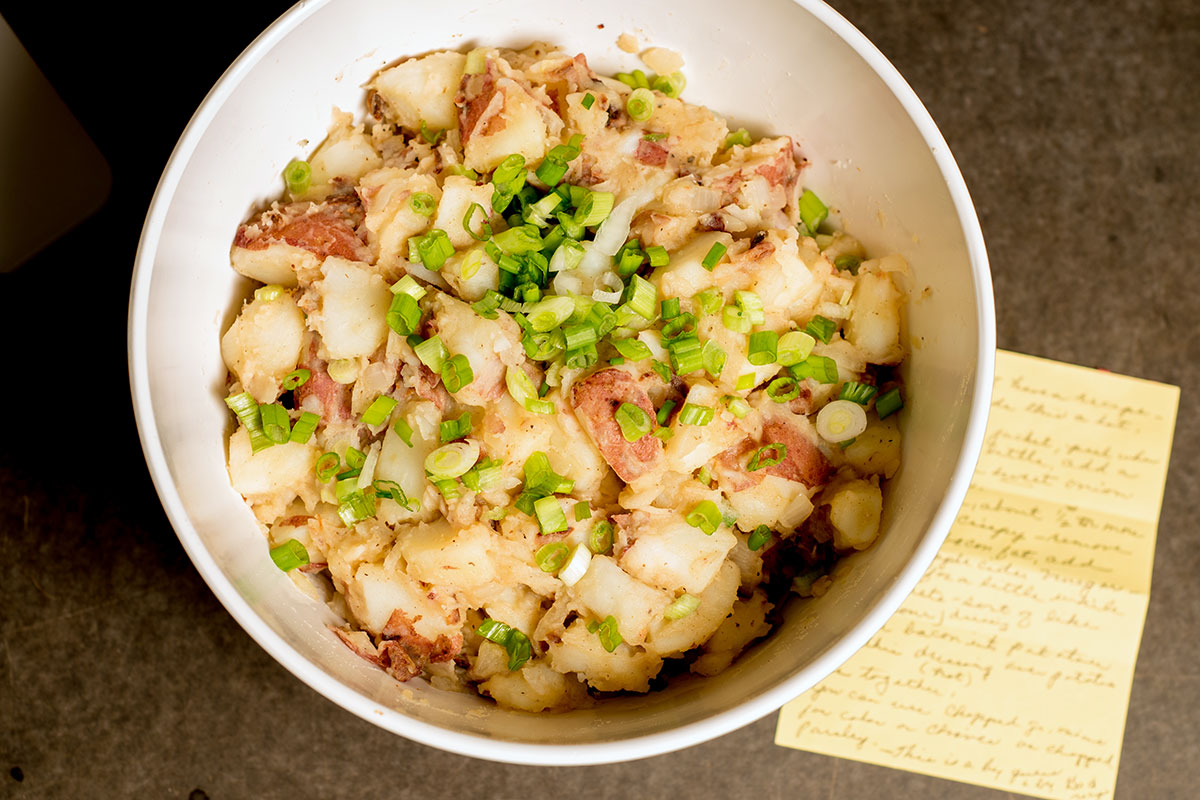

Although I didn’t witness my grandmother give my mother-in-law this recipe, I knew instantly the circumstances surrounding its exchange. My husband and I had a very small wedding several years ago, and we held a summer barbeque to celebrate it with our very large extended families. Even though the event was catered, my grandmother had insisted on bringing food. The hefty bowl of potato salad she provided—which she describes as “sort of a spin-off of German potato salad” in her recipe—sat on the buffet table for guests to enjoy. My mother-in-law had complimented her on it, and my grandmother said that she would send along instructions for making it. The recipe I held in my hand was evidence that she had kept her promise.

This potato salad is not necessarily a holiday dish—it’s more of a general-purpose, get-together type of food. It’s one of those blessedly filling and shockingly caloric staples of Anglo, upper-Midwestern family cuisine. I remember its presence at Easters, Fourth of Julys, and a few Christmases, but I never expected it to have the resonance that it has now.

So, in this year like no other, this article is about my grandmother, her life, and instructions on how to make a now rather remarkable potato salad.

Doris Rykal Marion

My grandmother, Doris Marion (née Rykal), was born in 1928 in Cadott, Wisconsin. She was the daughter of first-generation Bohemian Americans, and I grew up hearing about their difficult life working on their small farm. One of my aunts reminded me recently just how hard that life was, and how they made the most of the foods they grew or had on hand. The potato salad is just such an example: the family stored their potatoes and onions in their root cellar, and they cooked them in the bacon fat that no one ever threw away, as well as in the vinegar they made themselves. This recipe “must have tasted so delicious in the dark of winter,” my aunt told me.

Doris was the only girl out of six children, and I heard quite a bit about the misadventures of her brothers when I was growing up. They were nicknamed Curly, Peanuts, Fuzzy, Jug, and Jimmy. If she ever told me the sources of these nicknames (except for Jimmy, of course), I cannot for the life of me remember them.

She married my grandfather, John Marion, in 1948, and their home soon grew to include five children of their own, including my mother. Throughout their adolescence, Doris worked, and worked hard. She held jobs at a local shoe manufacturer, at a finance company, and after several decades she retired from her position as a dental assistant.

Those who knew my grandmother best, however, will remember her deep and lifelong love of country music and for playing acoustic guitar. My own memories of her largely involve music—talking about music, watching music, and oftentimes creating music. Although early on I demonstrated that my particular talents lie elsewhere, she always hoped I would return to the musical fold one day (although sadly for her, I did not). I remember that she even asked my husband when we first started dating what instrument he played. She was disappointed to learn that he did not play one. However, he soon proved that he had other redeeming qualities, so that was that.

Perhaps most importantly, Doris Marion was a force of nature. I will remember her always as a potent synthesis of fire and ice. She was a born performer, the life of the party. She always had a story and a joke, and she was the magnetic center of any room she entered. She loved babies and small children. And while she was a devout Catholic, she lived her life on her own terms, which was something I always admired about her. Her time on Earth was punctuated by passionate stances and unwavering resolve.

To describe her life in her own words, I refer to her notes on the potato salad: “I really don’t have a recipe…this is by guess and by God.”

My grandmother died on St. Patrick’s Day 2020—just at the outset of the pandemic. Like countless others this year, her passing was not marked in the way she had imagined it would be. My family did the most possible in light of public health orders, and they held a small socially distanced wake for her, which I watched from my home a thousand miles away. The live stream was something that my cousin and his children arranged. It made my surreal tragedy less so, and I will always be grateful to them for that. In June, the family held another event, an outdoor funeral that was much closer to the send-off my grandmother had been planning for decades. I think she would have been happy to know that her meticulously planned funeral playlist was honored faithfully. Because of the distance, however, this was yet another goodbye I couldn’t give her.

And that brings me back to that little slip of paper I found in my mailbox one sunny day in November. Perhaps I felt the potency of Doris’s memory so deeply because I was never really able to say goodbye to her. Perhaps it is also because our collective lives have been so profoundly disrupted this year; we have all felt the breathtaking enormity of time and space in one way or another.

But I suspect that there is also more to this, that it has nothing to do with the events of 2020, and that its trappings live in that physical recipe. Irish poet and scholar Seamus Heaney once described our material surroundings as “temples of the spirit,” imbued with “that double sense of great closeness and great distance.” Most of us have felt that sense of great closeness and great distance in our own lives, regardless of global circumstances. That’s certainly what happened when I held that recipe, when a pathway opened between Doris and me. When I remembered cooking with her, singing with her, and laughing at her jokes. When I also remembered that those things would not happen in quite the same way ever again.

It was also in that moment that I remembered to call my mother.

Doris Marion’s Potato Salad

- Boil potatoes in jacket, peel when warm

- Cool a little, add a medium chopped sweet onion, salt and pepper

- In a fry pan, add about ½ lb or more bacon, fry crispy

- Remove, leave the bacon fat, add sugar and apple cider vinegar

- Boil this for a little while (boil to taste—sort of like a sweet and sour dressing)

- Crumble bacon into potatoes

- Pour hot dressing over potatoes

- Toss together

- You can use chopped green onions for color or chives or chopped parsley

“My mom made this a lot…Let me know if you try it—good luck.”

And just last week, I did try it. Although I wished that my grandmother had sent along more luck. Perhaps more experienced potato salad-makers will be more successful at making this—I kept scratching my head over her instructions. I could hear Doris gently scolding me when I did something wrong, just like she used to. However, I could also hear her saying, “Well, who cares what it looks like? As long as it tastes good.” In the end, it did taste good, and it tasted just like I remembered.

Emily Buhrow Rogers is an ACLS Leading Edge Fellow at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She is grateful to her mother and aunt for reading and commenting on an earlier version of this article. She is also feeling particularly lucky to have such a kind and thoughtful mother-in-law.