I love my last name—Max. Lindsey Max. It feels so powerful and cool, like “maximum” or “to the max.” I take pride in being a Max and all that comes with it, good and bad. Like a true Max, I love desserts. I hold grudges. I have high anxiety—or, as my cousins refer to it, “the Grandma Gladys gene.” I’m stubborn. And I’m hilarious.

But when I was seventeen, I learned my name isn’t Max.

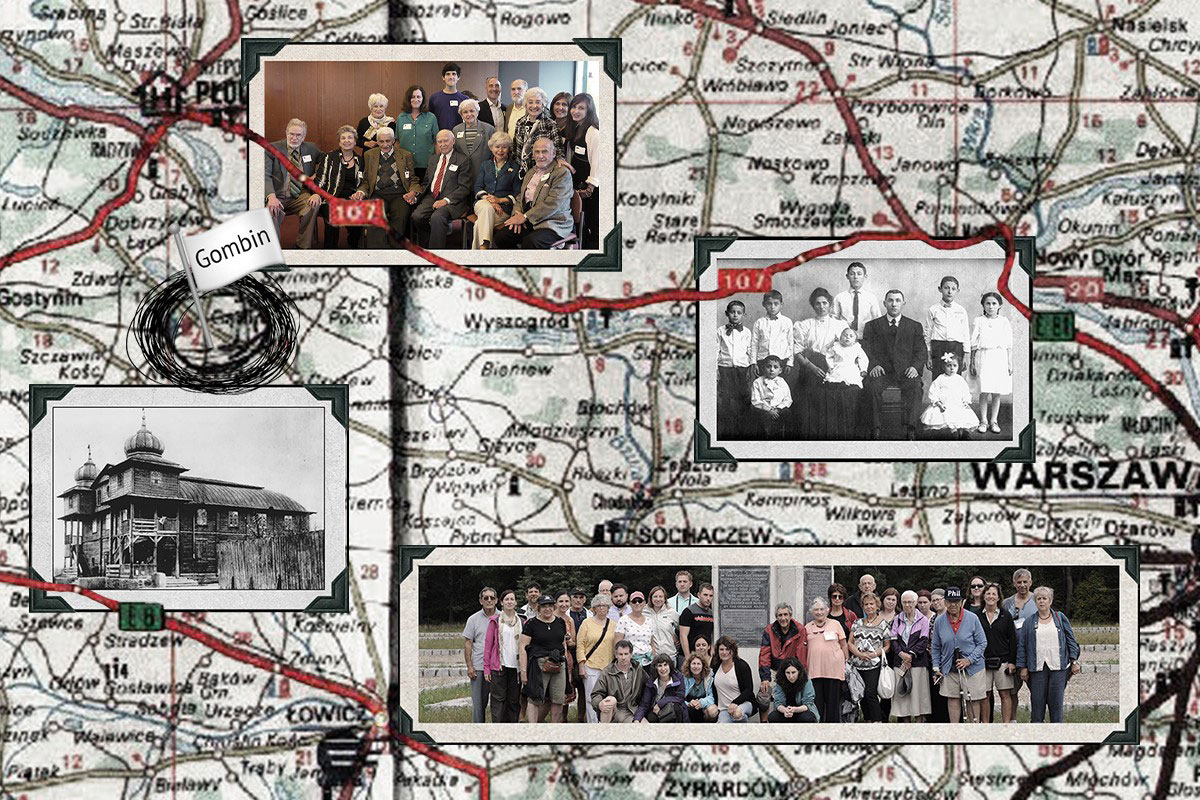

Michael Kaplan, a distant cousin by marriage, was researching our family’s ancestry. He discovered that we came to America from a shtetl (Jewish town) in Poland named Gąbin—Anglicized to “Gombin.” He discovered that relatives we believed died in the Holocaust were actually alive and living in Israel and Brazil. He discovered that when we lived in Gombin, we were not the Max family; we were the Manczyk family.

Manczyk. Michael told me that his wife, my dad’s cousin Ellen, vaguely remembered hearing the name as a child, “but we didn’t know how to spell that for sure!” And with that combination of “N-C-Z-Y-K,” it’s easy to see why. I never could have pronounced it on my own.

Nevertheless, the news filled me with pride. I had never truly felt I had a heritage. As with millions of other immigrant families, our connections to the past had eroded away as my relatives aspired to assimilate, leaving me with only a few grains of familial knowledge. But now, I knew my country of origin, my shtetl of origin, and my name of origin. I had new relatives all over the world. I had a history.

I wanted to learn more. So, when Michael mentioned a “Gombiner Society” dedicated to the legacy of the Jews of Gombin, I grabbed a shovel and dug deep—into the organization’s publications and my own series of interviews with its members. I never expected to unearth how connected this society is to my family’s history.

*****

In May 1892, my great-great-grandfather Abraham Manczyk left his home in Gombin and became one of the 12 million immigrants who would pass through Ellis Island on a journey toward a better life. I can only imagine how overwhelming the change must have been for him—to leave Gombin, a shtetl of about 5,100, and arrive in New York, a massive city of nearly 2.7 million. Of course, it’s possible he wasn’t overwhelmed at all, and this is purely me projecting “the Gladys gene” onto him.

Regardless, Grandpa Abe adjusted. He sought out his landsleit (literally “landsmen,” fellow Jews from the same European hometown), and found Sam Rafel, Max Jacklin, and the Kraut family, among others. He joined these Gombiners in their conviction to abide by the teachings of the great Rabbi Hillel: “Do not separate yourself from the community.” Adhering to the values of kehillah, mitzvah, and tzedakah—commitment to community, religious obligation, and philanthropy—they established an organization in 1920 to aid Gombiners in both the United States and Poland. This landsmanshaft (mutual aid society formed by landsleit) would eventually come to be known as the Gombiner Society.

By 1920, roughly forty families had immigrated to the United States from Gombin, most of whom settled in New York and Newark. As these families began to prosper, they wanted to provide assistance to the needy in Gombin. They formed the Gombin Relief Committee, and, after two years of fundraising, Grandpa Abe and his wife, my great-great-grandmother Minnie, traveled to Gombin to deliver the money they had collected. They brought along their sixth child, Charlie—an unruly teenager who they didn’t trust to leave at home.

By 1923, this committee officially became known as the Gombiner Young Men’s Benevolent Society. Their benevolence was more than financial, however. They purchased sections at two Beth David Cemeteries to keep the landsleit together—even in death. Current board member Dana Boll emphasized the significance of this to me: “It’s one thing to resettle people, but it’s another thing to provide community space to bury. Because, if you think about that, then that means that eternally you will be in the community.” During a 1937 relief trip to Gombin, they arranged with a local doctor to treat poor Jews free of charge and send the bill to the society.

In the mid-1930s, new chapters formed in Chicago and Detroit, and, in 1939, the Newark Gombiners broke away from the New York Gombiners to form their own chapter. Each chapter established their own Ladies Auxiliary Committee. The women fundraised and organized social activities—events which are fondly remembered.

“We had Gombiner picnics which were fabulous,” Gail Salomon recalls.“I have wonderful memories of that. It was a caravan of all the food, and there was a lot of game playing.”

Writing about her duties as president of the Ladies Auxiliary Committee, Yetta Rafel reminisced, “The Chanukkah parties were in a class of their own. They were festive with candelabras. They also brought in funds for the relief. The Purim parties were gay and colorful. Who can forget the choosing of Queen Esther?”

But none of the original members of the Gombin Society could have predicted the vital role they would soon play in keeping the heartbeat of Gombin alive.

At the outbreak of World War II, the society anticipated that, as in the first World War, the Jews of Gombin would need much assistance once the fighting ceased. “Our organization raised $25,000,” Sam Rafel wrote. “But, unfortunately, the end of the war brought the dreadful news about the Shoah [Holocaust, literally “utter destruction”]. During those terrible days, we received some letters from Jewish survivors from Gombin. We immediately began to help them.”

The society worked to locate Gombiner survivors, and “oversaw efforts to cut through red tape and managed to sponsor the immigration of over fifty families from Polish and German detainee camps,” Harold Boll wrote. In 1954 they built Beit Gombin (“Gombiner House”) in Tel Aviv, Israel, which served as a gathering space for Israeli Gombiners and a way to memorialize the Jewish community in Gombin that was destroyed. But their most meaningful initiative was the creation of the Gombin Yizkor Book.

Yizkor is a Hebrew word. It’s what we call the prayer service for the dead, literally meaning “May G-d remember.” A Yizkor book, however, specifically commemorates the people and communities lost as the result of persecution. “The Yizkor book wasn’t invented by the Gombiners; it was a world initiative to memorialize Jewish communities, and it fell naturally on the landsmanshaftn to organize these books,” Leon Zamosc explained.

Of the six million Jewish lives taken by the Holocaust, roughly 2,100 were Gombiners. Their homes and possessions were stolen. An anti-tank trench was carved through the cemetery and the matzevot (tombstones, literally “sacred pillars”) used to pave roads and build bridges. The synagogue was burned to the ground.

In the aftermath of these tragedies, the Gombin Society made a Yizkor book to ensure that the memory of Gombin was passed down l’dor va’dor— from generation to generation. In doing so, they honored the plea repeated by Jewish historian and activist Simon Dubnow before his death in the Riga ghetto in December 1941: “Yidn shreibt un fershreibt— Jews, write it all down.”

In 1969, after over ten years of searching records, gathering survivors’ stories, and collecting photographs, the society published the Gombin Yizkor Book. It contains maps, pictures, descriptions of Gombin—both before and during the war, the history of the Gombin Society, and memorial pages dedicated to those who did not survive.

In his introduction to the Yizkor Book, Jack Zicklin, of the New York chapter, wrote, “Our goal was to erect a monument through which the coming generations—the children and grandchildren of the Gombiner Jews—would be able to acquaint themselves with the ancient past of Gombin and the roots of their origin.”

With so many Jewish records destroyed during the Holocaust, the Gombin Yizkor Book is an invaluable resource.

*****

Before the Shoah, the Gombin Society was a family. But, after, as the society helped survivors immigrate to the United States, this notion of family took on an entirely different—and more solemn—meaning. Many survivors had no blood relatives left.

“That was his family. He had no other family,” Mindy Prosperi told me of her father’s connection to the Gombin Society. “On my mother’s side, I have family. On my dad’s side, that’s the only family I have.” For Prosperi, Gombiners are family because they’re “people who knew my parents, but who also share that empty feeling inside, that hollow space of having lost.”

“I had a family that extended beyond my blood relatives,” wrote Harold Boll. “To me family meant any and all Gombiners. There was little distinction made between blood relations and those who were Gombin survivors. I possessed a sense of belonging to a larger family—a Gombiner family. That family was there for me, to fill the void left by those who perished in the war.”

*****

As first-generation American Gombiners grew old and passed away, and, as their children went off to college, meetings became less frequent. The organization nearly disappeared—until Leon Zamosc and Harold Boll revived it in 1996 under a new name, Gombin Jewish Historical and Genealogical Society.

But Zamosc and Boll did more than reestablish the society. For over three years, they fundraised and organized projects that not only brought Jewish life back to Gombin, but also dignity to the dead.

They erected a monument at Chelmno to honor the Gombiners who perished there in 1942. They worked to restore the cemetery, which was being further desecrated by youth, who now played soccer on the empty field once full of matzevot. They recovered as many remnants of these gravestones as possible. These pieces, used by the Nazi to build bridges and roads, would soon build a memorial at the cemetery’s entrance instead.

In August 1999, they arranged a society trip to Poland, during which these memorials were unveiled at dedication ceremonies. “After an absence of almost sixty years,” Boll wrote, “Jews returned to Gombin, at least for a little while.” This trip—the first of many organized by the newly named society—was commemorated by Minna Packer in her 2002 documentary film, Back to Gombin. Packer’s nephew, Joe Richards, helped film.

“I’m very, very happy that I went there to see where my grandfather came from,” Richards told me. “It helps me understand what he came from, what he went through, what my family went through.”

The pilgrimage took Gombiners not only miles away, but years away.

“I was surprised at how much of the old town is still there,” Michael Shade recalled. “The whole of the street plan is still there. Some of the names of streets have changed, but then you look at the plan of the streets, and you’re walking down the same streets that they walked down. The buildings are different, but the street is the same street. You’re going from here, to there, and it’s the same journey.”

*****

The more I learn about the Gombiner Society, the more nostalgic I become for a close-knit community I never experienced—a community that looked out for each other: You need a place to stay? Live with me. You need a job? My brother needs an apprentice. You’re looking for a Nice Jewish Boy to marry your daughter? My nephew is a total mensch—it’s beshert! It’s destiny!

My dad tells me stories about Grandpa Abe and Grandma Minnie’s large family, a family with nine children—until what Grandma Minnie thought was a tumor turned out to be child number ten, my great uncle Andy. I picture them living in Newark never far from family, whether blood relatives or fictive kin.

It’s a stark contrast from my own childhood. With each generation, we’ve spread out more and more, to the point that none of my relatives lived near me when I was growing up. For this reason, my grandpa’s funeral was one of my fondest memories: it was the only time in my life when the entire Max side of my family was not only together, but also able to spend quality time with each other. No one needed a funeral to spend time with their loved ones when the Gombiner Society was in its prime.

While, in the early days, the Gombiner Society served to keep the community together, today, it helps us reunite. While it used to help bring friends and family to the United States from Gombin, it now helps Gombiners return to their ancestral homeland. While it used to collect money to help the Jews living in Gombin, it now collects money to properly memorialize the Jews who died there. The effort to hold onto the memory of Gombin, however, has remained constant.

*****

DNA testing databases have, to a certain extent, helped communities discover and reconnect with ancestries lost or stolen. This information is valuable, but genetics doesn’t go far enough. DNA might tell me the names of my ancestors. It might tell me that my great-great-grandparents Abe and Minnie were first cousins—yuck. It might tell me that my great-grandparents Nathan and Fanny were also first cousins—double yuck. But DNA can never tell me who they actually were, what their lives were like, or whether they, too, loved ice cream and held grudges. For those insights, I have to rely on material records and family lore.

Like any game of Telephone, family stories change with every retelling: details forgotten, embellishments added, facts misunderstood. Who knows how much truth is left after a few generations? Did my great-great-grandparents own dairy farms in New Jersey? Yes. Did Grandpa Abe invent the concept of delivering milk to customers’ houses in refillable jugs, thus becoming the first milkman? Highly unlikely.

But the Yizkor Book tells me what life was like in Gombin when Grandpa Abe was there. It tells me that he was one of the founders of the Gombiner Society, and that he traveled back to Gombin in 1922 to distribute the funds they had raised to help the needy. It tells me the stories that he no longer can.

While some stories change over time, some family knowledge is lost altogether. I’ll never know how our name went from Manczyk to Max. I’ll never know when we stopped speaking Yiddish or cooking Polish food. I’ll never know when we stopped remembering Gombin.

What I do know, however, is when the Max family reconnected with Gombin. In May 2013, organizers held a Ninetieth Anniversary Celebration of Gombin Societies at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. I was fortunate enough to attend, along with around seventy-five other ancestral Gombiners.

Of these attendees, only two were born in Gombin. One of them was my great uncle, who, until three years prior, I had no idea existed. At eighty-three years old, Luzer Manczyk traveled to the United States from São Paulo, Brazil, to reunite with his long-lost relatives and landsleit. Cousin Ellen recalled that, “At the end of the event, overwhelmed by feeling of love from his American family and a new connection to Gombin, his birthplace, Luzer pronounced it to be one of the best days in his life.”

*****

The Gombiner Society taught me how broad the term “family” can be. We use familial words to refer to non-blood relatives all the time. This is our chosen family—the people who we care for and support, and who do the same for us.

Some members of the society immigrated with their relatives. Some didn’t have any family at all. What they found was that the community formed far from home—the people with whom we celebrate holidays and milestones, the people who look out for us, the people with whom we have a shared history—is a family, too.

“In the shtetl—and Gombin is the mirror of all shtetls—everybody was related.”

—Ada Holtzman

Lindsey Max is an intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She received her BA in anthropology and religion from Emory University and her MFA in photography from the Savannah College of Art and Design. She would like to thank the Gombin Jewish Historical and Genealogical Society for their help and generosity.