Finnish artist Eija Koski sees inspiration all around her. A maker of himmelis—traditional Finnish geometric mobiles made of straw—she finds not only her materials but her muse in the rural farming village where she lives and works.

“I have himmeli glasses, so I see himmeli everywhere,” she said during a recent interview over Zoom. “I see the patterns. It can be fabrics. It can be some other floor or outside in nature. Everything comes with these himmeli glasses.”

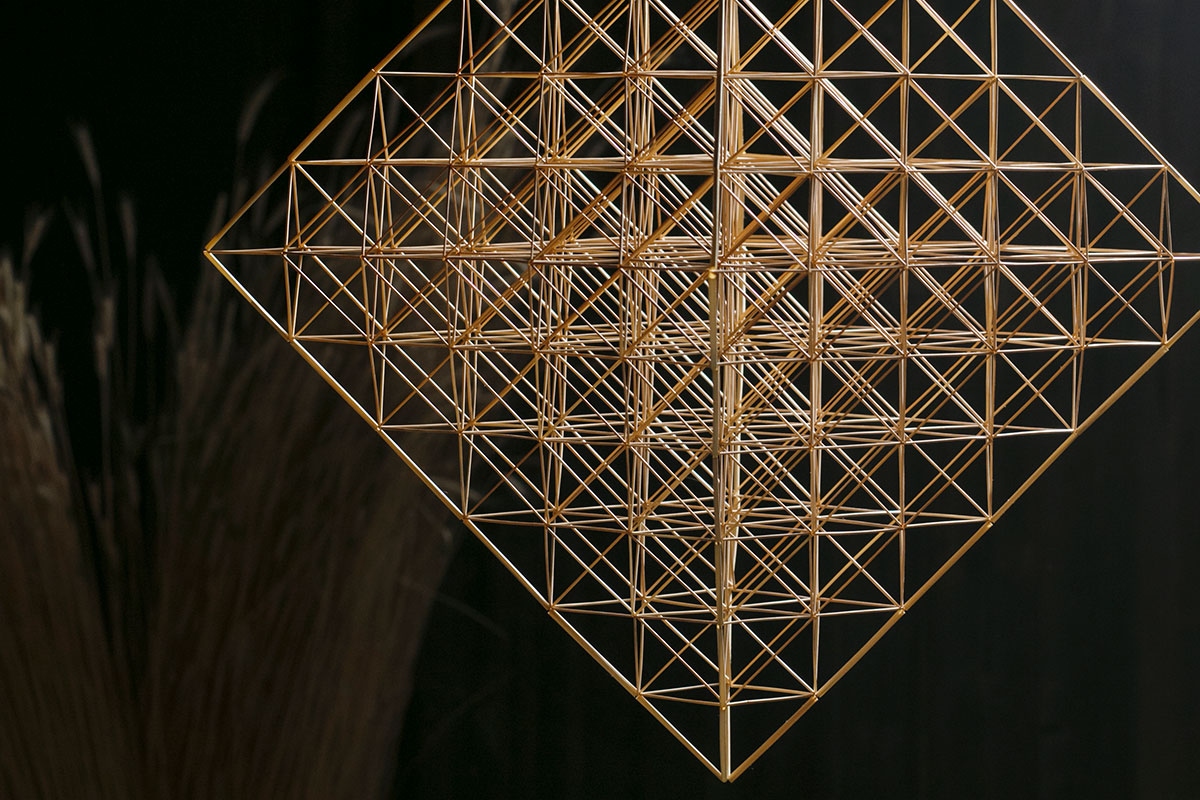

At play with this poetic inspiration is the more tangible, mathematical language that underwrites the art form. When a himmeli is in motion, it creates magic. Spinning slowly, it creates different geometric patterns at different angles, to a mesmerizing and meditative effect. “You have to stare at it. You are just forgetting everything else,” she described. There is a push and pull between discord and harmony: at certain angles, the patterns are indiscernible, but when the himmeli lines up just right, the shapes become crystal clear.

This harmony is central to its hypnotizing beauty. It’s what Eija calls the “hidden secret” of himmeli: the sacred geometry.

The Platonic Solids—a set of five mathematically significant three-dimensional shapes studied by the philosopher Plato—are present in the geometric designs of himmelis. These recognizable shapes give himmelis a universal appeal, easily translated and understood across cultural and linguistic barriers: “People around the world recognize the geometry and mathematical language or beauty behind it,” Eija described.

Thanks in part to this universality, himmelis have been experiencing a revival, not only in Finland but around the globe. Although the geometric designs might seem reminiscent of modern home décor, they predate Christmas trees as a Finnish holiday tradition. Eija has become world-renowned for her intricate artworks and has played a significant role in the revitalization of this tradition. More than merely decorative, this traditional Finnish folk art form has played a part in contemporary community building around the world.

Camera and edit: Ananya Tanttu, Lokal Helsinki

Music: Philippe Nash

Eija began practicing the tradition around twenty years ago, but her fascination with the art form began in childhood, when she saw her first himmeli. When she married her husband, a farmer, and moved to a rural village, this interest was reignited by the straw surrounding her.

“I fell in love with the straw before himmelis,” she said. From then, she took coursework and apprenticed with a master artist, Hanna Löytönen. Now, she has published three books on the subject, with a fourth title on the way. From her childhood interest to a lifelong passion spurred by her change in surroundings, himmeli has been a connecting through line of Eija’s life.

According to Eija, there are three important elements of himmelis. “The first thing, the most meaningful thing, is that it is hanging from the ceiling.” This is so that the himmeli is in perpetual motion, gently spinning and swaying with the breezes of the house. Secondly, they should be symmetrical from their hanging points, creating harmony with repeating geometrical shapes and lines. Thirdly, himmelis should be made with straw. Rye straw is the traditional material, and it remains Eija’s material of choice, but artists today also use plastic, metal, and paper straws, so long as they have holes for the thread that binds them together.

These three elements are what make himmeli, well, himmeli, and when one is absent, Eija has to ask herself whether she is still honoring the tradition. She experiments with designs that do not fit all three qualities, such as bracelets and wall hangings, but she says, “if I change one of these elements, I'm discussing with myself, ‘is it still a himmeli?’”

Still, however, she views the idea of himmelis as dynamic. “We are not living in museums,” she said. “So the tradition, with us, also develops. We can develop it and continue it.”

Despite their seasonal roots, for Eija, making himmelis is a year-round practice: there hasn’t been a day in the last ten years when she hasn’t practiced this craft.

Her process is deeply anchored in her environment, creating art from her family’s farm work. She begins in August in her fields, when her husband plants rye. She harvests it by hand, cutting strands measuring around six and a half feet long, making it the perfect material for himmelis. She leaves the straw to dry on her roof for several weeks, until it turns from green to golden brown. Once dry, she cuts the straw at its joints and separates it by thickness, in order to make proportionally sized himmelis, something that Eija emphasized as crucial to maintaining their aesthetic purity and harmony. “So, we have done a lot of work before starting the actual work.”

“Before starting making the himmelis, I have to know how many pieces I need.” A medium-sized mobile, for example, took around 800 individual pieces of straw to create. She cuts each piece by hand with scissors. While many of her students find this arduous, Eija feels that it is an important step. She described how, in some of the workshops she leads, students bring in contraptions to cut the straw more efficiently. She finds this amusing—especially that it is always the men.

“For me, I don’t comment on the time, how many hours you do it. It is the process itself.”

Although Eija tries to plan her work out in advance on paper, she can only do so much to plan three-dimensional designs in two dimensions, so she allows some room for improvising and reworking.

Once the pieces are cut, she begins to thread them together. Although it is the crucial element—quite literally the tie that binds—the thread is meant to be invisible, creating a magical quality as the ornament hangs in the air. “The basic rule in Finnish himmeli is that you don’t see the thread at all. It’s very thin, and you hide the thread inside the straw. So the thread is not meaningful. The straw and a space, they are meaningful. They negotiate with each other, the material and the space.”

Although himmelis have long been a part of Finnish culture as Christmas decorations, the tradition had begun fading away by the mid-twentieth century. “It was almost disappearing, the tradition and the makers,” Eija said. “But everybody in Finland knows what is himmeli. Everybody has beautiful memories from childhood for a mother or grandmother who made himmeli.”

At that time, there was only one book on the subject, written by Eija’s mentor Hanna. It didn’t have colorful photographs, only some technical descriptions of how to make himmeli. Eija remarked that her Hanna “would be very happy to know that I have now written three books, which are published in five languages”—with the upcoming in six. Eija’s books include instructions but are also colorful, vibrant, and full of photographs, history, and folklore. “She would be happy for himmeli, I think.”

The word himmeli has German and Swedish roots—emerging from the word for “sky” or “heaven” in each—but its use in the Finnish language has no translation. Eija credits this with helping the art form spread beyond Finland: “In English it is himmeli. In Japanese it is himmeli. It is himmeli in every language. So people find me, and I find himmeli people around the world.”

The art form itself, too, requires no translation. The universal geometrical designs and the simplicity of the materials have allowed it to spread and speak to artists and enthusiasts across the globe—among both rural and urban populations, younger and older generations, and from craft hobbyists to architects.

Most notably, the art form has seen great interest in Japan. Eija has visited Japan four times, where she has done workshops and exhibited work. She was shocked, in one workshop, to learn that twenty-nine of thirty participants had made himmelis before.

In Japan, she met a woman named Yoko who used himmeli-making to create a sense of place and establish community. When Yoko and her husband and daughter moved from Tokyo to a rural farmhouse in Hokkaido, she turned to making himmeli, looking for something to do, using the wheat they grew on their farm. Mirroring Eija’s own life, Yoko found harmony and beauty in the natural materials around her as she adjusted to rural living.

Although at first himmeli-making was a tool for Yoko to stave off isolation, it soon became much more: a facilitator of community. “There were eight women in the village in the same situation, and they created the himmeli community. They started to make himmelis together, and they had himmeli courses in their own villages, then in Hokkaido, and then around Japan.” When Eija was invited to visit, “it was a wonderful occasion to see, to realize that himmeli is not only decoration—it is connecting people.”

Through her workshops, books, exhibitions, and international trips, Eija actively works to pass on the himmeli tradition to future generations in Finland and beyond.

“Himmeli is my duty, to bring it to the world.”

Himmelis help establish and maintain customs, relationships, and shared spaces. In this way, artists like Eija are continuing their cultural traditions, building a worldwide community, and making meaning out of the natural world around them.

“We have Nokia, the mobile phone, in Finland, and it has a slogan, ‘Nokia, Connecting People,’” Eija said, “but I say ‘himmeli, connecting people,’ as well.”

Joelle Jackson is an intern with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She is a second-year Wells Scholar at Indiana University, where she is studying folklore, anthropology, and theatre.

Photos were taken by Katja Lösönen, Rita Lukkarinen, and Akito Ezura. Special thanks to Suvi Järvelä-Hagström and Katri Källbacka at the Embassy of the Republic of Finland, Washington. D.C.