The community you live in strongly shapes the soundscape of your life story. Why? Because human culture and the natural world dictate not only what we hear but also how we listen.

Depending on our background and values, we experience the sounds of our community in different ways. A neighbor’s windchimes may provide a relaxing backdrop to your meditation practice, or it might be a constant irritation intruding on your movie night. You might fail to notice the ’70s folk tune coming from a passing car, while the sound takes your Chilean companion back to the Santiago of his youth.

Sounds may be powerfully evocative, yet temporary in their effect, and because of this ephemeral nature each sound we hear becomes a singular experience, or story, colored by our perceptions and memories of the event. Even so, in a basic sense, many of the sonic stories we hear are universal within the human experience, and knowing that is important to my occupation.

My personal relationship to sound stems from my background in music performance and a profound love of film, two interests I combined into a career, becoming a sound designer for visual media. Years ago, before pulling back the curtain of movie magic, I believed that sound and picture happened simultaneously on location. It may surprise you to learn that in a film, the visual and sonic tracks are created separately. A person like me edits, designs, and mixes in the sounds that make up the tapestry of a movie soundtrack. Sound designers create the illusion of reality: a transparent marriage between audio and visual that brings the universality of sound into the storytelling sphere.

When presented with the image of a river, most humans can quickly conjure to mind the sound it makes. A pet collie in the United States barks the same as one in Brazil, the same as one in France. This type of functional sound design, such as putting a recording of a river to an image of a river, or a recording of a dog bark to the gaping jaws of a hound is easy to do. The nuanced and fun part of my job concerns creating and selecting the most emotive versions of these sounds to help tell a story.

We are all active participants in sonic stories. You don’t need to be a sound designer. We draw inspiration from our surroundings, as is the case with all modes of expression. My small corner of Los Angeles, California, is a residential neighborhood comprised of small to mid-sized apartment buildings and single-family homes. My apartment unit has a modest porch that stands about six feet above the street. Here, I like to sit and listen. One evening around twilight, I was taking a break from work on a film soundtrack when I heard a bird call. It was not an inherently unusual occurrence. However, recently the narrative of my sonic story had shifted, which threw this bird call into sharp relief. These were unusual circumstances, as we were a week deep in the stay-at-home order caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic. I was finally hearing what this meant.

The typical soundscape of L.A. is easy to conjure. You have heard it countless times in films and television shows: the constant rumble of distant traffic, the whir of cars, such as those that speed down my street, the ever-present, oppressive, cyclical drone of police and news helicopters, and the comically pervasive mating call of the garbage truck. For me, at their least intrusive, these sounds create a baseline buzz of white noise that I can tune out. At their most intrusive, they are stressors and distractions that prevent me from relaxing and doing my job.

Tonight, these were largely absent. One car, let alone a continual stream, is more than enough to drown out even the most persistent bird cry. Yet, I could hear my bird clearly, and my bird possessed a fascinating and unusual repertoire that seemed to mimic the sounds of car and building alarms. As I stood listening, I was surprised that I could hear its call echo off the face of an apartment building across the river before bouncing back to me on my porch. It seemed like the bird, perched high in a nearby palm tree, was playing, excited to hear its own voice. If this were a scene if a movie, I could not have designed a more fascinating and idyllic soundscape.

Altered soundscapes are one of many manifestations of community change wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. These past months, we’ve grown accustomed to seeing fewer cars on the road, a reduction of air pollution, a resurgence of animal life, and marked shifts in urban acoustic environments around the globe. In my three years living in L.A., I’ve never experienced such low levels of ambient noise. Intimately scaled human sounds, rather than the mechanical drone of industry, now occupy the fore—the murmur of hushed conversation of couples on their evening walks below my porch, gritty footfalls upon the concrete, and the chitter of squirrels vaulting from power line to branch and back. My neighborhood had taken on the character of a soundscape meticulously crafted and mixed for a movie neighborhood, with easily identified layers, and discriminately edited and spatialized birds, rather than the indistinct sonic wash of normal reality. I was enjoying the change of sonic scene.

Sound is a primary sense, but humans are not equally attuned to its role in life. Many of us hear but few listen. I trained in the art of listening because I am a sound designer. My mind continually parses sonic stimuli as I move through my day. Where other tasks may occupy someone not so sonically minded, I almost can’t help it. This means that though the broadband noise floor typical of many city soundscapes masks most of the other sonic actors at work, I can still hear them because of my background. The pandemic largely removed this noise floor, creating a soundscape primed for easier analysis and study. How many people, hoping to keep their spirits up in this time of pandemic, are now actively listening to their life’s soundtrack as though for the first time?

Active listening has deep roots in the work of R. Murray Schafer. In the late 1960s, Schafer founded the World Soundscape Project (WSP), an education and research group with the mission of studying the acoustic interaction of humans with their environments to achieve ideal, ecologically balanced soundscapes optimized for human health and happiness. A healthy community will possess a healthy, balanced soundscape. The sounds accompanying that community will reflect the values, desires, and activities of the people who comprise it. Communities articulate these in their small businesses, in the strains of music traveling through the air, the hiss of sizzling food, which floats down residential blocks, the laughter of children at play. All these facets of a community have a sonic manifestation.

Imagine a tight-knit historic community marked by block parties, communal porch gatherings, and a vibrant children’s street hockey league. One day a developer buys up a swath of this community’s homes and begins razing them to erect concrete high rises. Suddenly, the scene, and therefore soundtrack, shifts. We swap the music from the block party for the constant drone of a jackhammer and sizzling burger patties on the grill for the roar of a bulldozer. The sounds of construction, which drown out all other sounds, now dominate the soundscape.

This is neither a flourishing community nor a healthy soundscape, and even after the last brick is laid, what is it they’ve built? The soundscape of the community is altered forever, for better or worse. It is this that Schafer and the WSP sought to illuminate: human and community health have tangible sonic markers.

Many of us have grown used to these industrial noises. If we think of them at all, we call them “normal,” and normal is comfortable. Normal is happy. The absence of these typical noise sources can provide a marked and sometimes shocking contrast. While you may be accustomed to this level of homogenous noise, it does have a negative impact on physical and emotional health. Noise elevates stress levels, blood pressure, affects sleep patterns. Imagine again our hypothetical neighborhood assaulted by bulldozers and jackhammers. Where will that block party happen now? The dust and noise from earth-moving equipment prevents relaxing on the porch with a friend. You cannot discount the emotional toll of the absence of these community interactions. Even if you manage things, they will sound and feel differently because any conversation must now compete with the construction.

Every action we take, no matter how large or small, has a sonic consequence. We, by nature of being human, are all sonic actors, so we all have a role to play in designing our sonic environment, although at dramatically differing scales. My community of sound designers are explorers and purveyors of compelling sonic experiences. We listen for sounds with novel intrinsic properties. We collect these sounds by recording them. We trade our recordings, as someone else might trade baseball cards. Sometimes a project calls for a sound you don’t have, but your friend does. After we’ve captured our sounds, we manipulate them through editing and processing techniques to create the soundscapes that are heard throughout media. Viewers watch these films and disseminate our sonic ideas throughout their homes, which in turn, have an impact on their own personal soundscapes.

A film I recently worked on presented some thought-provoking sonic challenges. A pivotal scene of the story takes place in a bright, verdant meadow. As the scene unfolds, it becomes apparent that the meadow exists only in the mind of the protagonist. In narrative “reality,” he is sitting in an apartment nestled in the heart of a city. The point of view of the protagonist, shared by the audience, is in the meadow represented on the screen. He does not hear the meadow. Instead, he hears the “deafening” sound of silence. My task was to create this auditory experience for the audience.

In designing this scene, I wanted to emphasize the deafening nature of the silence. I wanted to approach things metaphorically, rather than literally treating silence as the absence of sound, because I felt it was truer to the emotional experience of the character. I created a designed environment, using an immersive surround drone, which evoked a sense of claustrophobic pressure—imagine putting your ear up close to quickly rotating fan blades. My hope is that when this soundtrack reaches you, the viewer, on your couch, it might cause curiosity, perhaps leading you to reevaluate your relationship to silence.

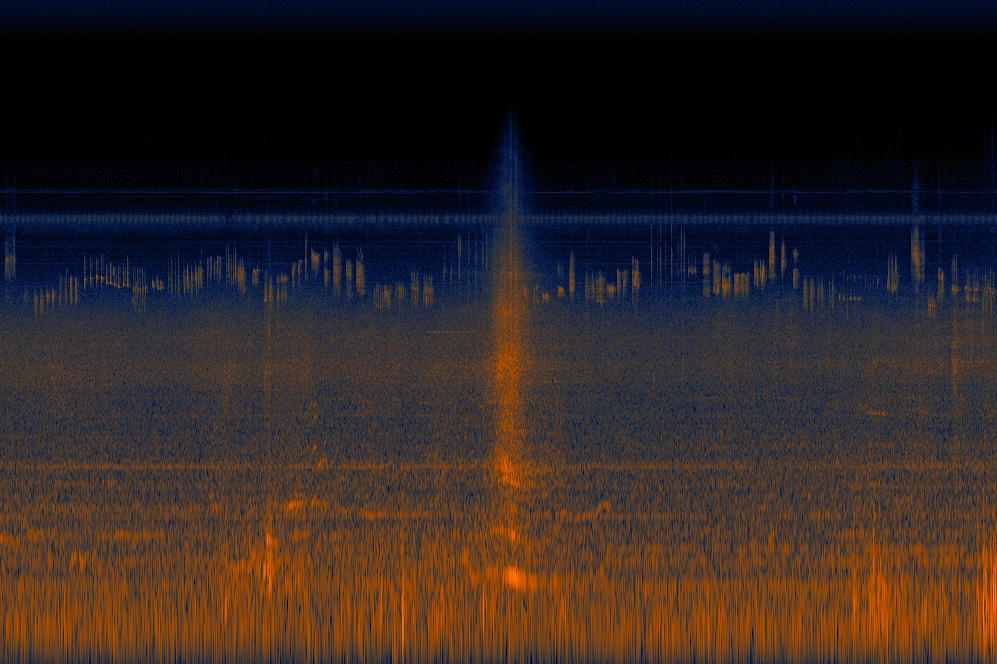

The building blocks of the sound designer are recordings. This is how I achieved my “silence” design. When listening to the world through a microphone, it quickly becomes clear how many moving parts entwine to make up a soundscape. A recording of my porch bird, for example, is not only a recording of the bird. It is a recording of the reverberation of the area in which the bird is making its noise. It is a recording of crickets that take refuge on my porch. It is a recording of the ever-present, if dramatically pandemic-attenuated, hum of traffic. It is a recording of the drone of air conditioners. Once you can hear the distinct elements that make up a soundscape, you can analyze them critically. Critical listening means being able to identify these sonic elements with only the aid of your ears.

All actions have a sonic consequence and all sounds tell a story. Through critical listening, anyone can begin to identify the perceptual effect of sounds. Then you can act to mitigate or exaggerate those effects through the manipulation of the sonic environment. A sound designer executes this analysis in a film by selecting and manipulating specific recordings to create, for example, a naturescape that is achingly sad, made desolate and cold by the whine of a mountain wind, or a joyous and exuberant soundscape replete with bird song and children’s laughter. Once trained in the practice, it becomes difficult to extricate yourself from this filter completely, and the outside world begins to take on the character of your auditory point of view.

Recordings may be the building blocks of a sound designer, but there are many ways you can design the soundscape of your community. Sound is an expressive medium. But what sounds good to you may be completely different from what sounds good to me. The first step in designing a soundscape that serves all community members well is to critically engage with the sound of our community. Moving forward, let us use this time of COVID-19 to begin to identify the soundmarks of life that we wish to hear. I want to hear my porch bird more clearly. It makes me happy. To achieve this, I will choose to avoid running my air conditioner and make a commitment to walk more to reduce the level of ambient noise on my street.

How do you want to design your sonic environment? First, take the time to listen. Close your eyes. What sounds can you hear? How do they make you feel? Is the general sound level constant, or are there periods of quiet, punctuated by brief, loud intervals? Try to identify specific sound sources. Is this what you want your community to sound like? If not, think about a single action you could take to become a designer of your acoustic environment. It might be as simple as planting lantana to attract the energetic thrum of a hummingbird.

Listen, and be well.

Marinna Guzy is a sound artist, researcher, and writer focused on the intersection of art and social justice, especially in relation to culture and the environment. She currently serves as the supervising sound editor and sound designer at Raconteur Sound.