The email heading was “Fwd: Poems.” The message body was a personal note from a friend and colleague: “Dear Friends, For some poetry in the time of coronavirus – please follow instructions below.” What followed made my folklorist’s “Spidey sense” tingle: a good old-fashioned chain letter, this one asking for a poem to be sent to the first person on the list, and to blind copy “20ish” friends so as not to break the chain.

The same day, my husband reported that he had received another chain letter from a friend, this one asking for a “quarantine recipe.” In both cases, the forwarders were friends and/or colleagues. And the messages were customized to address the anxieties and boredom of being cooped up during a pandemic.

Intrigued, I immediately started researching the history of chain letters and the phenomenon of sending them during times of stress. According to a major fact-checking website, this type of chain message has been with us since the Middle Ages at least. Another source—perhaps less reliable—reports a hoax letter supposedly written by Jesus and recovered from under a rock, examples of which circulated as early as the 1700s. Some chain letters are threatening and rather scary—by breaking the chain, you will suffer bad luck or even the direst of consequences. The plot of at least one chain-breaking horror movie portrayed multiple deaths.

In contrast, the pandemic-inspired messages are non-threatening and promote a feeling of sharing and belonging to a wider community. One version of the letter states, “We’re starting a collective, constructive, and hopefully uplifting exchange... We have picked those we think would be willing and make it fun.” How harmless can you get? A recent New York Times article calls the letters “annoying,” but one person they interviewed admitted, “It feels nice when someone tags you.” Despite a warning also circulating that the letter might contain a harmful phishing scheme, there seems to be nothing malicious about it. Or so I think.

I conducted an informal poll among my immediate friends and family, then widened the circle via Facebook and personal messages. I quickly gathered about a dozen of the poetry messages and a smaller sample of the recipe messages. What interested me as a folklorist was the rapid and widespread dissemination—just my small sample revealed versions from Western Canada, Scotland, Luxembourg, and all over the United States—and noticeable variations in the letters. In Folklore 101, we learn how items of folklore spread through time and space and exist in “variants”—think of the many ways the blocks of a log cabin quilt can be assembled or changes in words of summer camp songs.

Chain letters existed in my childhood days (before the proliferation of the Xerox machine and way before the internet) as handwritten missives, passed through the mail or by hand among school children. Answering the letter and sending it out was laborious and time consuming. These days, you can fill in a couple blanks with a few short taps and clicks, and these letters circle the country and the globe at fiber-optic speed, picking up subtle variations as they go.

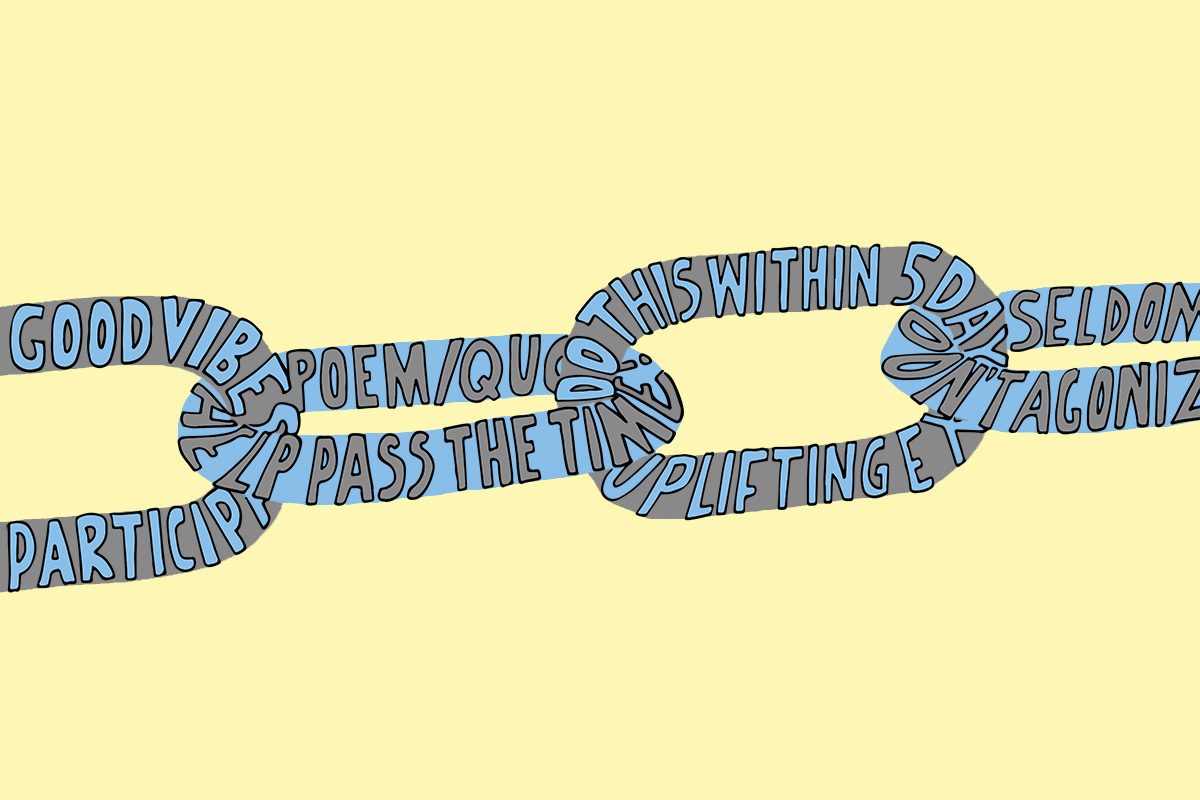

The poetry message was a particular gold mine of variation, which I break down here by section for analysis:

- Personalized introductory message

- Opening explanation

- Instructions for continuing the chain

- Closing statement

My limited research shows that this particular chain letter dates to at least 2014 and probably back much further; it resurfaced after the 2016 election, especially among women. The wording of the body of the message has changed somewhat since the 2014 version, but it is unmistakably the same sentiment. The subtext of which is, “do this or you will disappoint countless women needing inspiration.”

The personalized introductory message, like the one in the opening of this article, draws you in, bringing you to believe that someone you know began this chain, and therefore you will not only be letting countless nameless women down, but some altruistic person in your own sphere will go inspirationless as well. One friend of mine from Canada was convinced of this: “From [the name of the person] who emailed it to me and the wording in the instructions, I think this one originated here in Edmonton from one of the counseling/help centres.” Indeed, many people who forward the chain letter find it necessary or preferable to preface the actual forwarded chain letter with some personal justification as to why they are participating.

The opening explanation is the beginning of the chain proper. In the poetry message, it exists in two basic forms: as a “women’s collective” or as a more inclusive, non-gender-specific plea. My examples were forwarded almost exclusively by women, and some of them tag “women leaders.” Some of the letters add an addendum addressing the international recipients of the letter, or at least those whose first language is not English: “If you’d like to send a poem in your own language and provide a translation, please do so!”

Instructions have fewer variation, though it is curious to note that somewhere along the way, the number of required recipients via blind copy changed from the specific number of twenty (which seems standard in chain letters these days) to “20ish.” It is also interesting to note that two words in the letter, “favorite” and “agonize” are spelled in many versions in the European/British/Canadian manner as “favourite” and “agonise,” thus hinting at its origin. In some, Americanized spellings indicate either editing by the sender for a mostly American audience, or a new strain of the letter originating here in the United States.

The “closing statement” is meant to convince the recipient that this is a fun, important, or comforting-in-times-of-stress thing to do. The statement of the poetry letter always starts the same, giving additional incentive to continue the chain: “Seldom does anyone drop out because we all need encouragement” or, in others, “new pleasures.” Perhaps this statement provides a clue to the age of the letter, as one blogger writing about the 2016 version jokes, “When is the last time you used the word ‘seldom’?”

Despite the fact that the majority of my informal survey respondents said that they absolutely never participate in these kinds of letters—and in some cases were very annoyed by them—some percentage of recipients worldwide obviously keep the chain going, or else we would not be getting these messages. One source of my research speculated on the number of letters that would be returned if everyone participated; according to her math, by day thirty-five of the chain, the originator would have 25.6 billion responses.

Some of the letters list a person to contact if you do not intend to continue the chain. In the interest of research, I attempted to contact the person listed in one version to find out if she had any insight into the origin of this iteration of the letter. My message triggered an automatic reply stating that the recipient was receiving such a high volume of mail that she could no longer accept messages.

I did not personally answer the poetry chain letter, but I did forward the recipe message, which seemed to me more practical. I have received only three recipes so far, but I have also been rewarded with email notes from friends far and near telling me that they never participate in this sort of thing but instead update me up on their pandemic lives.

If you have not received one of the poetry or recipe letters, you needn’t feel left out of pandemic chains altogether. Just forward this article to 20ish of your friends, and see what happens!

Betty J. Belanus is a curator and education specialist at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage who has been trying to avoid chain letters since her childhood. She is currently sheltering in place with her husband at their vacation home near McConnellsburg, Pennsylvania.