Preshow. Each morning, Vivian Ireland, manager of Marvel Cave at Silver Dollar City, conducts an inspection at least one hour prior to opening. She checks lighting systems, water pumps, and equipment like belowground telephones. She clears mud, wipes handrails, monitors and assesses any changes in the cave environment. After extended periods of rain, she looks for safety concerns that may have resulted from flooding, debris that washed onto the walkways, and any animals that may have sought shelter that are not natural inhabitants.

Dark and empty, the cave might seem like just another feature of nature. But when the clock strikes 9:30, it’s showtime.

Caves like Marvel are some of the oldest performance venues in America, spaces where for hundreds if not thousands of years people have gathered to tell stories, worship, and experience music and adventure. They began with water, working underground to wear away passages and long chains of underground tunnels. Some of these tunnels are still filled with water. We call them springs. Others dried out long ago. These, we call caves.

There are more than a few kinds of caves in the Ozark region, but what’s important to know is that for 700 million years, they formed slowly, winding their way through deposits of limestone. A huge concentration—around 7,000—sit in the Missouri-Arkansas area, and a small set of these have been developed by the people of the Ozarks into performance venues, cared for by families of music lovers. Lying deep in the Ozark Mountains, the Ozark show caves are part of a vast underground network that has quietly shaped culture for hundreds of years.

Over the last century, families and entrepreneurs developed these spaces for locals and tourists, so that, to this day, they echo with the sound of local voices, live music, and applause.

But how does one become a cave keeper? Vivian Ireland tells us the secret to forging a good working relationship with all things cavernous: “Patience! Mother Nature has her own idea on how a cave should function, and that does not always coincide with our manmade best-laid plans.”

Bruce Herschend is son of Jack Herschend, the co-owner and former CEO of Herschend Family Entertainment Corp., which owns Silver Dollar City. He hails from a long line of cave keepers, a perfect person to speak about the challenges and rewards of running a cave.

“A show cave is a small business at its core that has a natural resource as its focus,” Bruce told me. “If the operator has less than 40,000 annual attendance, the profit margin is so tight that the operator needs to know a lot about electric and plumbing, marketing, hiring, training, leading people, environmental protection, graphic design, HR, hydrology, biology, OSHA regulation, insurance, and much more. He or she cannot make many errors. It’s long, hard work.”

The work of making the caves habitable and hospitable stretched far further back than families like the Herschends. Native American tribes like the Niúachi (Missouri) and Osage flourished in the region. They frequently used the caves as temperature-controlled shelter in the winter, on hunting trips, or as they migrated through the region. Homesteaders trekking west settled the area around the Missouri River, bringing their own folk cultures with them. As the settlers began discovering these cave systems, they began to tame and adapt them to for use as storage rooms and as informal gathering spaces.

As the culture of the Ozarks changed during the Civil War, both Union and Confederate troops occupied and mined the caves for saltpeter, a key component of gunpowder. It wasn’t until after that terrible war that Americans began to see them as places for leisure and fun.

As the twentieth century dawned, the middle class expanded, and the people of the United States, including young, Midwestern cavers, demanded athletic and leisure pursuits. And they were willing to pay for them. During this period, several of the show cave operations became associated with resorts that offered additional attractions such as rental cabins, swimming, fishing, and hunting. In the 1870s and ’80s, the Chautauqua movement brought adult education programming in the evenings. Caves were ideal settings for these extravagances of oratory, musical, and other performance entertainments.

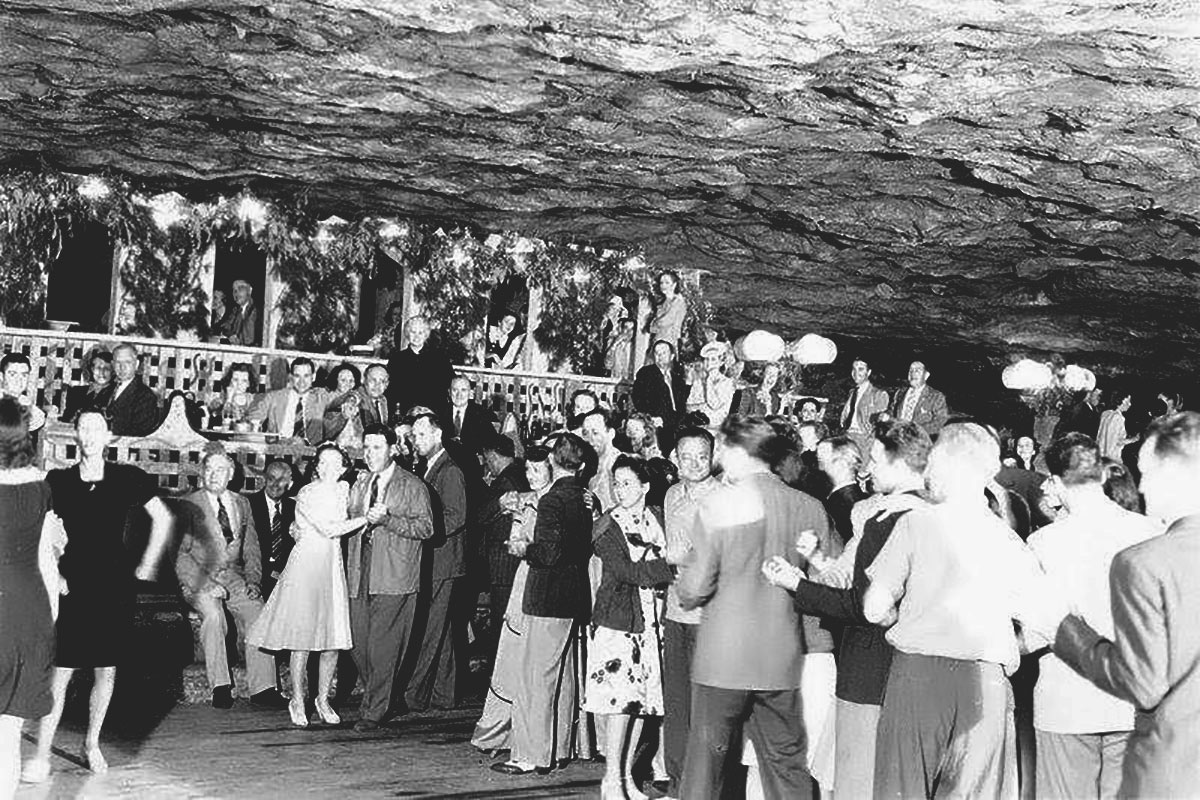

From 1885 to 1925, the Ozarks witnessed a craze for summer cave parties. Some property owners charged a modest admission fee, drawing families from nearby cities. Bands played dance music. Vendors sold barbecue and soft drinks. In Missouri, show caves became an especially popular pastime. Some of the first electrified structures in Missouri were caves, and some of the caves opened in this period are still in use today.

“We’re just a small batch of family-owned businesses, entrepreneurs with a passion for what we do. You know, everybody loves people, and we’re all family businesses passed down through generations,” says Kevin Bright, co-owner of Smallin Cave. As keepers of the caves, his family has passed down both occupational and entertainment traditions from one generation to the next.

Show caves have always been family businesses. As the responsibility for caring for the caves was passed from parent to child, there began to develop a distinctive occupational culture. Marvel Cave is a great example.

In 1894, William Henry Lynch bought Marble Cave, since renamed Marvel Cave, and began charging visitors to tour it. As Bruce Herschend, the current owner, explains, “The Lynch sisters, Merriam and Genevieve, performed piano and opera, so their dad, William H. Lynch, carefully lowered a full-size piano through a hundred-foot sinkhole and down twisty ramps to make such events possible.”

In 1950, Hugo and Mary Herschend leased the cave from the Lynch family for ninety-nine years and began hosting square dances. The family modernized the cave with electricity and concrete staircases, and in 1960 the Herschends opened Silver Dollar City, a recreation of a frontier town that featured five shops, a church, and a log cabin. You can still go to Silver Dollar City today, now a theme park.

Was there ever a time when they thought their business was doomed?

“Yes. About once every ten years,” Bruce says.

Meramec Caverns, a fan favorite, was also passed down through the family. Les Turilli, the current owner, first worked in the caves as a boy. His grandfather first held shows in a tent, entertaining folks with music and drama. It was Les’s grandfather who was the first in the Ozarks to put electricity in a show cave. It’s said that Meramec set the standard for show caves that followed. In 1935, Lester B. Dill promoted the caverns to tourists through his invention, the bumper sticker, and his marketing claimed that the outlaw Jesse James used the caves as a hideout. Today, 150,000 visitors a year tour Meramec.

The special properties of caves gave license to the subterranean behaviors of communities, whether people were letting off steam at parties that lasted days or holding secret meetings of invented ritual and pageantry. Within a couple years after the start of Prohibition, caves were used by organizations who wanted to stay, well, underground. Drinking, gambling, and all sorts of carousing went on in the caves’ big speakeasy rooms.

Also in the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan enjoyed a brief period of popularity and acceptance, with new films like The Birth of a Nation taking the country by storm. The general community was sometimes invited to the Springfield KKK’s cave ceremonies to witness all but the most private of its rituals. In 1922, the Percy Cave property was sold to the Springfield conclave of the KKK, who changed the name to the Ku Klux Klavern and briefly held meetings in the so-called Grand Ballroom.

Because operating costs were low, caves proved to be a business that could weather the economic downturns of the Great Depression, not unlike today’s COVID crash. However, it was at the conclusion of World War II that attendance began to really pick up. Travel was easier. Many returning GIs couldn’t sit still. They wanted to see and do things.

Cave tourism grew, Bruce says, in part due to cave owners turning to live radio as a marketing tool.

“Jack and Pete Herschend, they would do a live segment, the radio person describing what they were seeing, then they’d go off air and string wires along to the next room and broadcast again, and again. Through long narrow crawlways, down the ninety-foot Grand Crevasse, and across the underground lakes in a homemade raft. Early in the adventure, Jack accidently knocked a rock onto his brother Pete’s head that bled profusely. Jack told his brother that ‘it didn’t look too bad’ and applied a patch of mud to slow the bleeding. They continued with the exploration and live radio show.”

During the Cold War years, advertised uses of the caves reflected the changing culture and anxieties of the times. Owners promoted the caverns as both tourist attraction and bomb shelter. Would it have worked? “At least, that’s what we advertised it as,” says Lester Turilli.

“Most show cave tours were redesigned in the ’50s and ’60s, and it was enough to inspire people to visit,” Bruce says. “People worked hard to get a little entertainment, and just seeing it and hearing about it was enough. The world has changed. Today, guests have greater expectations, and many show cave operators are trying innovations that will grab the interest of the guests and let them experience, rather than watch, part of the cave story. And these days it needs to be a story, not just something to look at.”

Parallel to the development of the music industry, cave keepers began to showcase a style of music their communities enjoyed: country. Local attractions became regional, due in no small part to the foresight of families who built music venues into existing cave spaces. In the late 1950s, the owners of Fantastic Caverns in Branson, Missouri, set up their largest room as an amphitheater. Live audiences came to see Farmarama which was nationally broadcast on NBC radio stations. Country music stars of the day performed on the stage. Buck Owens, Bobby Bare, Ray Price, Jeannie Riley, and Lefty Frizzell all headlined the show. soon after, cave owners turned their attention to TV.

“In the early days of television, producers were struggling with what content they thought people would be interested in,” Bruce says. “Live square dancing was popular, but in the summer heat, before the days of air conditioning, it was not practical. Jack and Pete and team built deep in Marvel Cave three large dance platforms, several ‘squares’ on each one, the live band on another, along with bleachers for a place to rest. The TV cameras were huge in those days—think refrigerator-sized. Huge spools of wire to get the broadcast out and a lot of new lighting in. The undertaking was epic, but extremely well rewarded. From coast to coast, people tuned into Ozarks Jubilee, one of three major factors that put Branson on the map as a serious entertainment and tourist destination.”

By the late twentieth century, Branson became one of country music’s most popular destinations, vying for the title with a faded Nashville. In 1993, an estimated 5.3 million people came to Branson from around the Midwest as well as all corners of the country. A small fishing resort community in the rugged Ozarks of southwest Missouri, it reportedly had more theaters than Broadway and boasted of more than one hundred performances a day.

The city received its entertainment start with a cave family. They were the Presleys, an Ozark family who first played the underground stages of the Missouri hills. “One of the musical families put a concrete pad in a Branson area cavern,” Herschend says. “They had folding chairs, a cedar stage with a cabin backdrop. The cave was cool and protected from weather. They used water from the cave to pump outside to the restrooms.” Folks packed the caves to hear their now legendary performances, even at night. So many, in fact, the caverns couldn’t hold them anymore.

While performing at the Underground Theatre, the Presleys realized two things. The first was the importance of cool air to an audience. The second was that their dream to own their own theater was not a crazy one. They left the cave circuit and bought themselves a piece of land on an isolated two-lane stretch of asphalt just outside of town. On June 30, 1967, Branson’s first live music venue the air-conditioned Presleys’ Theatre opened, home to one of Branson’s most beloved shows, “Presleys’ Country Jubilee.”

Today, many show caves are going strong, even in a world where tourism and ceremony are shell-shocked by the coronavirus pandemic.

“I think show cave operators are looking for opportunities to get people excited about caves,” says Hubert Heck, director of marketing for Fantastic Caverns. “There’s a lot to learn from caves, and operators are looking for the best way to share valuable information in a fun, relatable, and understandable way. The term ‘edutainment’ comes to mind.”

Is there competition between cave owners?

“Most cave owners have learned they can’t make it alone,” Bruce says. “The number of required skills is too numerous for any one person to have, and the budget won’t allow you to hire experts very often. Cave owner-managers have become a problem-solving and innovating team of friendly competitors. They gladly share what they’ve learned with other cave owners.”

What unites all cave owners is an understanding and appreciation of the mystical. To keep the culture alive is part of something bigger: “Caves are fascinating and mysterious,” Hubert says. “They have both scientific importance and offer enjoyment due to their mystery of the unknown. Providing opportunities for visitors to visit, feel inspired, and better understand caves might, we hope, encourage a new generation of scientists and conservationists.”

“You have to love the cave, and love showing it off,” Bruce claims. “Love and terror are the only things I know that would motivate someone to keep working this hard.”

Todd Mayo, owner of The Caverns in Grundy County, Tennessee, draws comparisons to mythologist Joseph Campbell’s description of the hero’s journey: “One of the stages is going into the innermost cave you fear that often holds the treasure you seek.” For seventeen seasons, The Caverns has hosted PBS’s Bluegrass Underground, proudly continuing the tradition of broadcasting American culture from beneath the earth’s surface.

Preshow. One early morning, Todd talks with me as he drives through the mountains to reach his cave and work. As we draw closer to The Caverns, he becomes more excited, turning our discussion toward broader human experience and the meaning of caves themselves.

“You emerge from a cave a different person, with a new gift. That treasure could be music. It could be a sense of confidence that you overcame a challenge. It could be an awe that strengthens you. If you’re a religious person, it might make you more honest, or bring you to think about the wonders of Mother Nature. It’s fundamentally intertwined with what it means to be human. I think the caves are a wonderful metaphor but a literal adventure.”

Jake Rosenberg is the producer of special projects at ALT and a graduate of the School of Visual Arts Masters in Branding Program, with a focus on brand lore. He was recognized by American Folklore Society for his work documenting the folklore of the COVID-19 pandemic.