Many in the Black community see Black hair as an art medium. But what is art without an artist?

“Growing up and watching my mom do my sister’s hair is a core memory,” says Kerry Riley, an African American studies professor at the University of the District of Columbia. “I can recall the smell of the hot comb on the stove’s open flame and hearing quiet yelps from my sister because my mom may have burned her scalp trying to straighten her hair. But it was something they bonded over—the touch, the care, the patience and time it took.”

Stories like Riley’s—really expressions of love—have been passed down for generations. In their tenderness, they reveal how central hair is to Black identity. They also illustrate the personal and social situations that can lead to the development of new hairstyles, a source of continuous artistic inspiration to the Black community. It’s important to consider these stories. Afterall, a critical part of moving forward is reflecting on history and the people who made it and why.

Two women born in the 1860s, both to parents who had been enslaved, are known for pioneering the African American beauty industry. With an understanding that hair health could improve the lives of African American women, Annie Malone developed products like scalp preparations and hair-growth formulas. With her success, she founded Poro College in 1902 in Missouri, training other Black women to treat and style Black hair. One of her students was Sarah Breedlove, who rose to prominence, under the name Madam C.J. Walker, for her own line of hair-care products and hair school, Lelia College in Indianapolis.

Although Walker is often mistaken for inventing the straightening “hot comb,” she heavily promoted it, and many of her products helped with the straightening process. The hot comb offered a much wider range of styles for Black hair. In the early 1900s, this proved a significant asset for Black women, allowing them easier assimilation into professional society; straight hair was seen as orderly. Walker’s work drastically reshaped the hair-care industry. Despite this, some African Americans debated whether the use of the hot comb pandered to Eurocentric beauty standards, a debate that continues today.

With the growing popularity of these straightened styles, definitions for what was deemed “good Black hair” and “bad Black hair” emerged. “Within the African American community, good hair is perceived as straighter and softer, while kinky and coarse is regarded as bad hair,” Riley explains. With “good hair” came more access to jobs and advancements that would influence social and economic status. “Bad hair” is natural, meaning no chemicals are used to alter texture and curl. Perms, relaxers, and texturizers all contain chemicals that are used to loosen natural curl patterns. In October 2022, the National Institutes of Health released a research study showing that some of these texture-altering products, those especially marketed to Black women, are directly linked to uterine cancer.

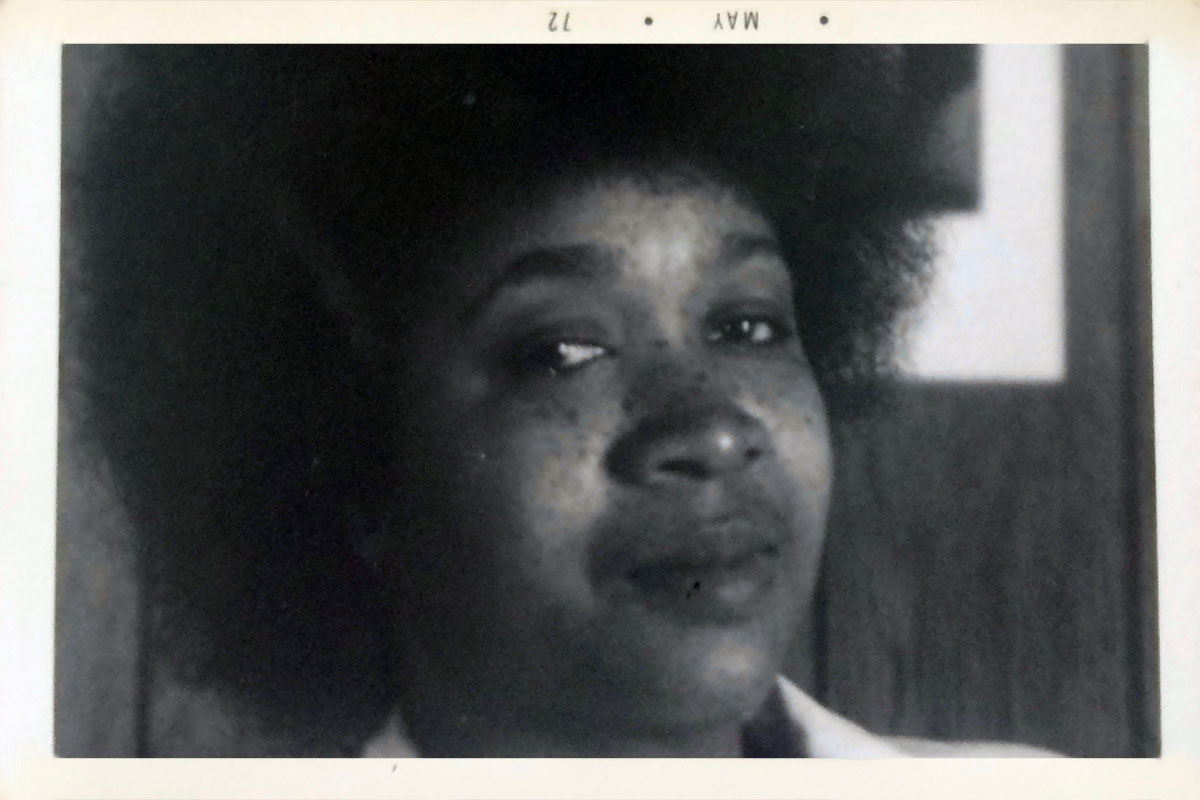

Throughout his life, Riley has worn his hair in various natural styles ranging from thick curly Afros to short-cut fades. He also wears a shaved bald style with various hats to accessorize. He learned about his natural hair at an early age, growing up in the 1960s and ’70s. From childhood, his hair was thick and coarse. Bullies preyed on him. Often, they were other Black students.

“Advertisements for Afro Sheen were everywhere,” he says. “It was a product used by many in the Black community to make hair much softer and shiny. I found myself beginning to use it.” Eventually Riley stopped using these products as he transitioned to different hairstyles.

Notions of Eurocentric beauty standards have caused great harm to non-white communities, stealing away our culture and capital and spawning self-hate. The Black Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s aimed to foster racial pride and economic equality and created political and cultural resources. With the movement’s emphasis on the importance of African culture, clothing, and natural hairstyles, the Black community shifted from straight, processed hair to curly, natural styles: gravity-defying Afros that could sit inches over your head, braids that could be as short as your pinky or drag down to the floor, and locs (dreadlocks) that could be styled up, down, or any form one could imagine.

These styles are odes to African culture. In ancient societies of the Wolof, Mende, and Yoruba, people wore braids to signify marital status, age, wealth, religion, and social class. With reclaimed cultural pride and interest, natural styles became mainstream and were eventually viewed as a pillar of the Black Power movement. They represent who a person is and where they’re from.

Restoring natural hair and texture to its proper level of respect plays an essential role for the Black identity today. As a young girl, future hairstylist Gara Auster wore her hair naturally and found her passion by working on dolls. As a teenager, she found herself transitioning to relaxers. “I think the only reason I got a relaxer was because I saw everyone else with one and was insecure. But I had to come to realize ‘good hair’ is not straight hair or less curly hair. No! ‘Good hair’ is healthy hair!”

Auster attended cosmetology school before working professionally and eventually opening her own Bossi Experience hair lounge in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. In that time, she realized that her hair is part of her identity, but it is not who she is. It is merely an extension of her self-expression. So, she made a big decision: she cut off her hair and regrew it natural. She described the transition away from relaxers as refreshing. “I was excited for a new start, but I did go through a period of insecurity. I didn’t feel as beautiful because I didn’t have long, straight hair.”

Auster’s insecurity soon turned into strength and appreciation. She learned to respect her hair, challenging herself through a series of styles and pushed boundaries. “I am a beautiful woman no matter how my hair is.”

More African American women today are transitioning from relaxers to natural hairstyles such as braids and locs. Kelo Williams, a “loctician” based in Hyattsville, Maryland, is seeing this firsthand.

Williams began styling hair as a teenager, mainly for close friends and himself. After receiving many compliments on his work, he opened a business, crediting his success to the unique looks he creates. He now travels across the country teaching courses on natural hair, locing and styling methods. His clients often tell him stories about the struggles of having natural hair in professional environments, but he also has his own.

“When I worked at Harris Teeter back in the day—I was about seventeen or eighteen—my manager told me my hair was getting ‘crazy’ and ‘super long,’” Williams recalls. “I asked them what they wanted me to do. They proceeded to say, they would have to discuss their decision because my hair was in locs. But, baby, I was out of there before they told me what to do because it didn’t matter. I love my hair, and I would not change it for anyone!”

Williams’s story is empowering because, too often, stories like his end with people cutting off their locs. Many bow to such discriminatory practices because they need a job or seek better financial standing or advancement. “I had a friend who was trying to work in the government,” Williams says. “And they were told they couldn’t because of their locs.”

In 2019, personal care brand Dove conducted a study among Black and White American girls between the ages of five and eighteen, which showed that 66 percent of Black girls in majority-White schools experience hair discrimination, compared to 45 percent of Black girls in other school environments. According to the report, 80 percent of Black women are more likely than White women to agree with the statement, “I have to change my hair from its natural state to fit in at the office.”

To end discriminatory actions against ethnic hairstyles, a group of African American women pushed for a law they called the CROWN Act, an acronym for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. The law originated in California, where it passed in 2019, and is now active in thirteen other states and thirty-four municipalities. It forbids discrimination of hair based on styles and textures in the workplace and in schools, and it is the first law of its type to be passed at a state level. (Watch Smithsonian curators Diana N’Diaye and Joanne Hyppolite discuss African hair history and identity with New Jersey Congresswoman Bonnie Watson Coleman in support of the CROWN Act.)

The act has a great impact on the Black community because it allows freedom of expression through the art form of hair. As Williams says, “Our hair is everything. It’s our crown. The people need to know, so let’s educate them and ourselves!”

Today, members of Black community are connecting through YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter, building new online communities centered on culture, fashion, and identity. More than ever, these groups encourage education around Black hair.

That exposure to various styles through social media has been beneficial to Milan Harris, a junior at James Madison University. She has grown to love and appreciate her hair the way it is, recognizing that her reddish color is not “the norm.”

“I went through a phase of thinking that I was prettier with straightened hair, but that is not the case,” she says. “I found myself missing my natural curls and the varying styles I can do with it. I like my hair better when I do it. I know what it needs, and I know what suits both my appearance and mood of the day best.”

Recently Black women have reclaimed hairstyles like low cuts or baldness. Some women do the “big chop” for health reasons such as alopecia (a disease that causes hair loss), some for a fresh start, or simply out of convenience for a low-maintenance hairstyle. Many women may receive negative comments and judgmental looks, but women are stepping away from conservative ideals. Often Black women gain a sense of self-love during this journey because the style is one that is not conceived as being suitable for women. They are leading their own paths, because why should others define what is best for you?

Black hair is continuously being reimagined, and many people are no longer asking for it to be accepted into a space—they are demanding. As generations continue to push the boundaries, and accept and uplift what once was rejected, more love is welcomed into a community. With that comes new creations.

Kamryn Bess is a curatorial intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a junior English major at the University of the District of Columbia. She is planning on pursuing a career in museums, specifically as an art museum curator. She would like to thank everyone who contributed to this article through storytelling, especially Kerry Riley, Gara Ausler, Kelo Williams, and Milan Harris.