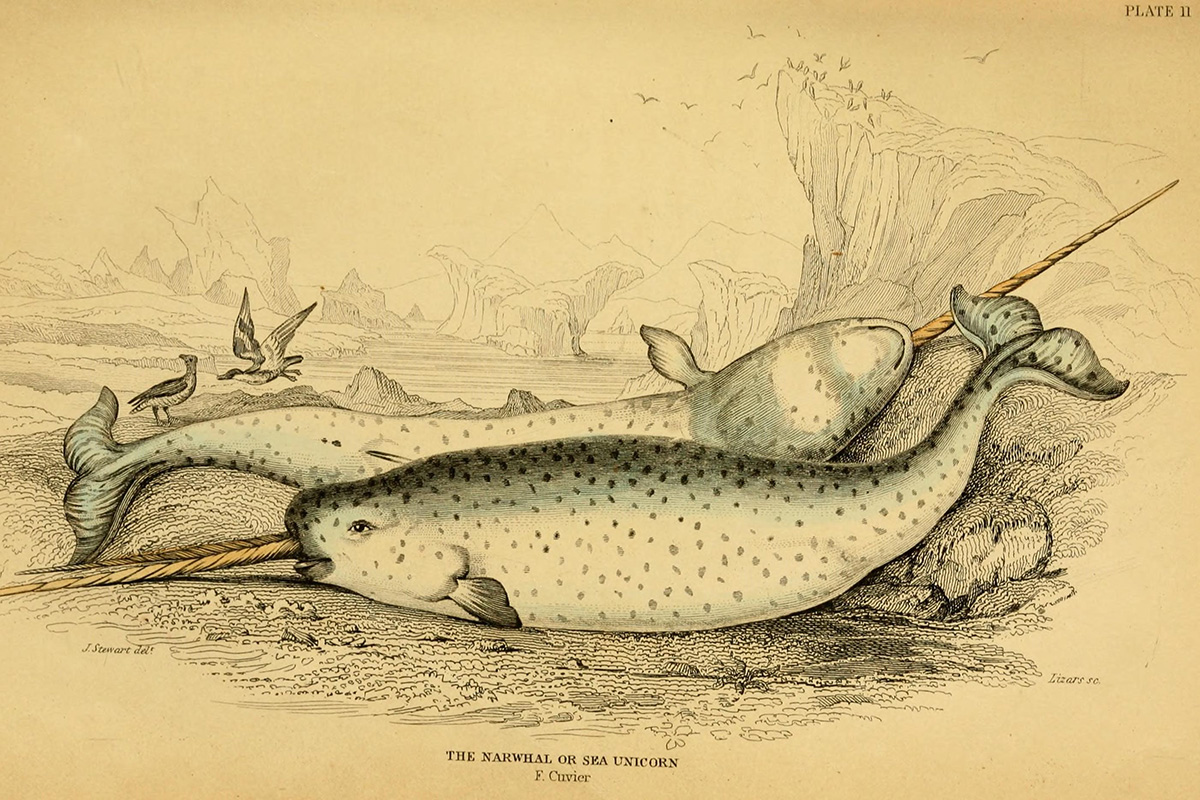

Marine biologists may be able to tell us why the narwhal has a distinctive spiraling tusk, but their scientific perspective differs from the explanation provided by the folklore of the Inuit people, who have lived among narwhals for many thousands of years.

According to myths collected among the Inuit in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the narwhal was once a woman with long hair that she had twisted and plaited to resemble a tusk. When the woman’s blind son lashed her to a white whale, she was drowned, but transformed into a narwhal. The son felt some remorse that he had killed his mother, but he also believed that the matricide was justifiable because of her deceitfulness and cruelty.

Before delving deeper into Inuit mythology, some definitions may be helpful. According to folklorists, a myth is a sacred oral narrative that members of a particular group or community (such as the Inuit) believe may explain the way things are. Myths tell us what happened in the remote past—before the beginning of time. Myths typically explain the creation of the world and its inhabitants, the activities of gods and demigods, and the origins of natural phenomena. Myths are serious; they are told not for entertainment or amusement, but rather to instruct and to impart wisdom. Folklorists never use the word myth to describe a false belief, as in “five myths” about this or that.

Bearing some similarity to myths are legends, which are also believed to be true—but which (in contrast to myths) are always set in the real world, with real places, and in real time, either the historic past or the present. A third type of oral narrative is the folktale, which is not set in the real world, but rather in anytime and anyplace. No one believes in the truth of folktales, which often begin with the phrase “once upon a time.”

As it so happens, two of the Inuit myths collected about the narwhal also begin with the phrase “once upon a time.” The Danish Inuit explorer and ethnologist Knud Rasmussen (1879–1933) collected one of the myths among the Inuit of Cape York, on Greenland’s northwestern coast. The German American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942) collected the second myth among the Inuit living on Baffin Island, on the western shore of Cumberland Sound, an extension of the Labrador Sea, which divides Canada’s Labrador Peninsula from Greenland. Reflecting the geographical nearness of Cumberland Sound and Cape York, the two myths bear some striking similarities, but also some significant differences.

Rasmussen’s version begins with the mother tricking her blind son; he kills a bear with a bow and arrow, but she tells him that the arrow missed its target. While she and her daughter enjoy delicious lumps of bear meat, the son receives meager shellfish. Boas’s version provides more details about the mother’s deceitfulness, and adds that she is the blind boy’s stepmother. Moreover, although the woman herself has “plenty of meat, she kept the boy blind boy starving.” However, his kind sister “would sometimes hide a piece of meat under her sleeve, and give it to her brother when her mother was absent.”

The transformation of the woman to narwhal begins when a pod of white whales swims nearby. The mother intends to harvest the whales, but the son (who by this time has regained his sight) lashes her to one, dragging her into the sea. According to the Rasmussen version, “she did not come back, and was changed into a narwhal, for she plaited her hair into tusks, and from her the narwhals are descended. Before her, there were only white whales.”

The Boas version provides more details: The son “pretended to help his mother hold the line, but gradually he pushed her on to the edge of the floe, and the whale pulled her under water….. When the whale came up again, she lay on her back. She took her hair in her hands and twisted it into the form of a horn. Again she cried, ‘O stepson! Why do you throw me into the water? Don’t you remember that I cleaned you when you were a child?’ She was transformed into a narwhal. Then the white whale and the narwhal swam away.”

Both versions of the myth provide postscripts in which the brother and sister leave their home and settle in another community, find a wife and husband respectively. But the key element in both versions is the transformation of their mother into the first narwhal.

The Inuit people have long hunted the narwhal, fully using its meat, skin, blubber, and ivory tusk for a variety of purposes. The myth of the narwhal explains why it is different from other whales in the arctic, and why the narwhal—as a former human being living in the Arctic—is so special to the Inuit people.

James Deutsch lived in Alaska, just below the Arctic Circle, while working for the Fairbanks North Star Borough Library in the mid-1970s. He is now a program curator with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.