Decades before Ann Landers ever put pen to paper, legendary Yiddish newspaper editor Abraham Cahan was writing his own advice column, A bintel brif (“a bundle of letters”). Beginning in 1906, the daily column counseled readers on everything from workplace dilemmas to dating predicaments to immigration snafus. A bintel brif ran for sixty years in Forverts, the largest and most successful Yiddish newspaper in the United States.

Immensely popular, Cahan’s daily column sired copycats in numerous Yiddish papers, spawning a multiformat advice industry in Yiddish popular culture. Songwriters penned multiple musical versions. At least two recordings, these from 1916 and 1922, sit in the commercial recordings collection of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. A 1908 version satirizes the frequently tragic and sometimes tragicomic situations A bintel brif addressed:

The letters in the song abide by some well-trodden melodramatic tropes: a man declares his love for his wife’s sister, a spinster finds love with a dodgy actor. It was these quotidian dramas that newspaper audiences found irresistible.

“Yiddish newspapers taught Jews about the world around them and served as guides to their new lives in big cities or in new countries,” says Eddy Portnoy, exhibition curator at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. “A perennial favorite that offered concise, emotional dramas followed by sage advice, the Yiddish advice column was similar to those that appeared in the English-language papers, which were also incredibly popular and went on to inspire, books, radio programs, and TV shows.”

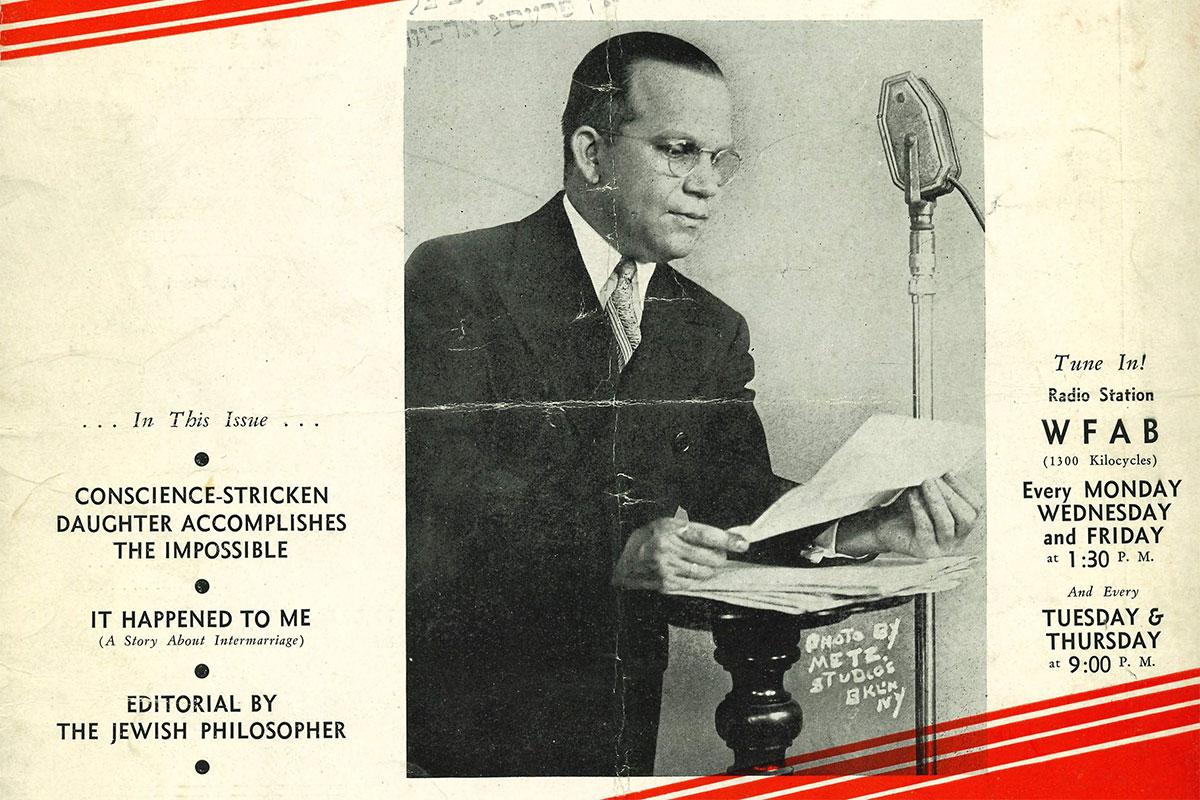

Yiddish advice made it to the airwaves as well. Perhaps the most famous advice program on Yiddish radio began its long run in 1931. Hosted by C. Israel Lutsky, Der yidisher filosof or “The Jewish Philosopher,” quickly became a hit. Tens of thousands tuned in daily. Before long, Lutsky became one of the most popular and best-loved figures in Yiddish radio.

Despite the popularity of the advice format, Der yidisher filosof’s sponsors were initially skeptical. They didn’t think that audiences would care for fifteen straight minutes of talking. The program’s runaway success proved them wrong, as the widespread appeal of advice columns translated seamlessly from print to radio. People were drawn to Der yidisher filosof for guidance, entertainment, and, crucially, a sense of community.

Everyday People’s Troubles

In an oral history collected by the Yiddish Book Center, Yiddish teacher Rebecca Levine recalls that her grandmother listened to two programs on the radio. One was Der yidisher filosof, and the other was the transparently titled Tsores bay laytn (“Everyday People’s Troubles”). The “everyday problems” listeners faced and the answers proffered by the hosts entertained Levine’s bobe (grandmother). Evidently, she was not alone. Yiddish radio fans flocked to Der yidisher filosof.

The audience was broad and multi-generational. Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe enjoyed the medium regardless of their level of literacy; their children and grandchildren were happy to listen to Yiddish programming, whether or not they used the language in their day-to-day lives. What brought generations together was—let’s just call it what it is—gossip. Yiddish-language radio grew in popularity at a time when the Yiddish theater, which had served as a key communal site for Eastern European Jews in the United States, was in decline. Radio entertained but also reinforced a shared ethnic identity.

Take one example from a listener grappling with her marriage to a non-Jew. In 1937, a woman named Sarah S. submitted an essay to Der Yidisher Filosof’s short-lived companion magazine covering her intermarriage and eventual divorce. Some of the essay revolves around the specific issues she and her ex-husband suffered as a couple, but she ultimately concludes that her interfaith marriage was never going to work.

“Nature was the driving force, society was the emphasizer, and custom completed the job,” she laments. “No one can successfully contend against these three forces for any length of time.”

In another question from the radio show, one anonymous caller, an Auschwitz survivor, sought advice for dealing with oblivious inquiries about her concentration camp tattoo, which she could not cover up in the hot summer months. These were universal questions—how to grapple with a dissolving marriage or deal with unwanted attention from strangers—but they were also distinctly Jewish.

As a specific Eastern European Jewish American identity developed, American Jews often turned to Yiddish media to figure out what it meant for them in their individual lives. The questions Lutsky fielded present good examples of the kind of quandaries they were facing, and Der yidisher filosof allowed Lutsky to opine on how to navigate them.

He actively sought to foster a distinct Yiddish American culture, going so far as to organize in-person meetups through the Jewish Philosopher’s League, which billed itself as “a successful challenge” to loneliness of the heart, soul, and spirit. Some of its activities were recreational, like hikes out in New Jersey, while some were directly related to the Jewish immigrant experience, like citizenship classes. The league sought to “preserve and strengthen the ideals of Judaism and Americanism,” positioning the two as separate but complementary. Many attended the real-life meetups, and Lutsky’s immense platform, Der yidisher filosof, enabled him to reach an audience with his ideas on what constituted appropriate American Yiddish culture.

Radio in Jewish Immigrant Communities

Entertaining as other people’s gossip is, it was especially salient packaged as a radio show. Yiddish radio was first and foremost a communal experience: listeners often consumed radio in groups, the same way people gather today for television watch parties. Radio programs regularly broadcasted religious holiday services and ritual events, an approach that had its schticky moments. Radio actor Rubin Goldberg broadcast his own 1928 wedding in all its glory, sponsored by Branfman’s Kosher Sausages. Although radio broadcasts couldn’t quite replicate in-person events, people enthusiastically gathered for listening parties, and rabbis debated whether one had to say “amen” at the end of a prayer delivered over the airwaves.

Despite the public way it was consumed, Yiddish radio proved an intimate listen. One of the most popular and influential fictional dramas, Nahum Stutchkoff’s Bei tate-mames tish (“Around the Family Table”), was literally centered around everyday domestic life. Through advice shows, which operated without the narrative constraints of scripted production, hosts engaged meaningfully and directly with the workaday concerns of their audience. There was a genuine back-and-forth of listener submissions, radio responses, and then, in some cases, listener responses to the radio responses.

Even the YIVO Institute, which ran its own radio show from 1963 to 1976, developed a program called Mentshn fregn yivo (“People Ask YIVO”) where staffers discussed community questions. As someone who regularly handles YIVO inquiries today, I cannot say that I would recommend this approach as mass entertainment. No matter! People wanted to know what other people wanted to know. If radio, and specifically advice radio, was a way to learn how to be an Eastern European Jew in America, both surface-level inquiries and personal dramas were meaningful, so long as they came from other community members.

Lutsky was well-situated to harness the intimacy of Yiddish radio into a fiscally successful program. He had worked both as a social worker and on the business side of Yiddish newspapers before transitioning to radio. Thus, he could handle the sensitive topics his viewers brought up, and because of his business background, Lutsky was savvy enough to package them such that they would make for intriguing radio. He made the advice column, an enduring American entertainment format, work for a Jewish immigrant audience.

The Legacy of Radio Advice

The American radio industry has long been multilingual and multicultural. Today, you can find immigrant-oriented stations on radio dials throughout the United States. Immense networks deliver advice to immigrants (many of them on unauthorized “pirate” frequencies), from national platforms like Punjabi Radio USA to local stations like Jambalaya Radio in New Orleans. A number of groups use the medium for dedicated cultural and language preservation projects, like Radio Bilingüe and Radio Indígena, both based in California. Many networks operate outside traditional commercial methods, choosing to broadcast via low-power FM, internet radio, and podcasts. Their shows reinforce shared culture and play a key role in transmitting information in communities where large numbers may not speak English or have reliable internet access. Radio programs and other local media platforms can serve as “digital first responders,” dispensing vital health and governmental information.

The advice-as-entertainment genre is still going strong. Advice columns proliferate, some in legacy media publications and others in low-key newsletters. Furthermore, you don’t need your own platform to dole it out. It’s easy for participants to get in on the action in popular forums like the relationship advice subreddit, to which millions subscribe. Advice-giving is a hobby in and of itself.

Of course, this is nothing new, as demonstrated by the story of sixty-eight readers meeting in a park to discuss a Bintel brif column and vote on the advice. And in the great tradition of the Jewish Philosopher, Jewish-interest media platforms like Tablet and Hey Alma continue to dispense advice with a Jewish bent. Even Bintel Brief runs occasionally, although now only online and in English.

Then, as now, advice programs provided practical information, spiritual guidance, and a sense of community.

“I know that many believe only stupid people turn to an ‘advice-giver,’ but that, I have learned, is a popular conception—and like most popular conceptions, it is far from accurate,” Lutsky once said. “Tragedy knows no barriers of money or intellectual capacity. A person in need of comfort is being only human when he goes where he can to get it.”

Hallel Yadin is an archivist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

References

Kelman, Ari Y. (2009). Station Identification: A Cultural History of Yiddish Radio in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Yiddish Radio Project. (2002). C. Israel Lutsky, the Jewish Philosopher.