From the window of my office at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, near the intersection of Seventh Street and Maryland Avenue SW in Washington, D.C., I can see the 1970s “Brutalist donut” that is the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and the 1960s International Style Orville Wright Federal Building, which houses the Federal Aviation Administration.

Most passersby and probably most of my Smithsonian colleagues have no idea that the FAA’s parcel of land was once one of the most notorious sites of slavery in the nation’s capital. I would not have known myself, were it not for two historical markers placed in January 2017 on the ironically named Independence Avenue, which separates the FAA from the Hirshhorn.

One of the markers identifies the site as the “Williams Slave Pen,” also known as the Yellow House, which disgracefully existed from 1836 through 1850 as a prison for enslaved people awaiting transport to the American South; the other discusses the larger historical context of slavery in Washington, D.C. What neither marker notes is that the Congressional legislation that outlawed such prisons was “An Act to suppress the Slave Trade in the District of Columbia,” which passed on September 20, 1850—170 years ago this Sunday—as part of the Compromise of 1850, an agreement that sought to avoid civil war between North and South.

The legislation begins:

Be it enacted . . . that from and after the first day of January, eighteen hundred and fifty-one, it shall not be lawful to bring into the District of Columbia any slave whatever, for the purpose of being sold, or for the purpose of being placed in depot, to be subsequently transferred to any other State or place to be sold as merchandize. . . . [and] That is shall and may be lawful for . . . the cities of Washington and Georgetown, from time to time, and as often as may be necessary, to abate, break up, and abolish any depot or place of confinement of slaves brought into the said District as merchandize.

The “Williams Slave Pen” and its horrors came to an end roughly months after the legislation passed. However, similar places continued to exist a short distance away, across the Potomac River in Alexandria, until the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution finally abolished slavery throughout the entire United States in 1865.

The history of legislation is typically not what we research at the Center. Rather we prefer what folklorists, such as Gladys-Marie Fry and William Lynwood Montell, have termed “folk history.” Usually defined as the personal history that people tell about themselves and their communities, folk history has the power to illuminate historical events in ways that more conventional history cannot—be it diplomatic, economic, intellectual, political, or social history.

Folk history is most often shared orally but may also exist in written form, especially if it emerges from voices that are underrepresented or even excluded from conventional historical sources. Among the latter are voices of enslaved people. For instance, when former President John Quincy Adams—while serving in Congress in 1837—attempted to introduce petitions from enslaved people to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, his pro-slavery Congressional colleagues alleged that in so doing Adams had “committed an outrage on the rights and feelings of a large portion of the people of this Union; a flagrant contempt on the dignity of this House; and, by extending to slaves a privilege only belonging to freemen, directly invite[d] the slave population to insurrection.” Presenting the voices of those who were denied their freedom, as Adams learned, can be risky business.

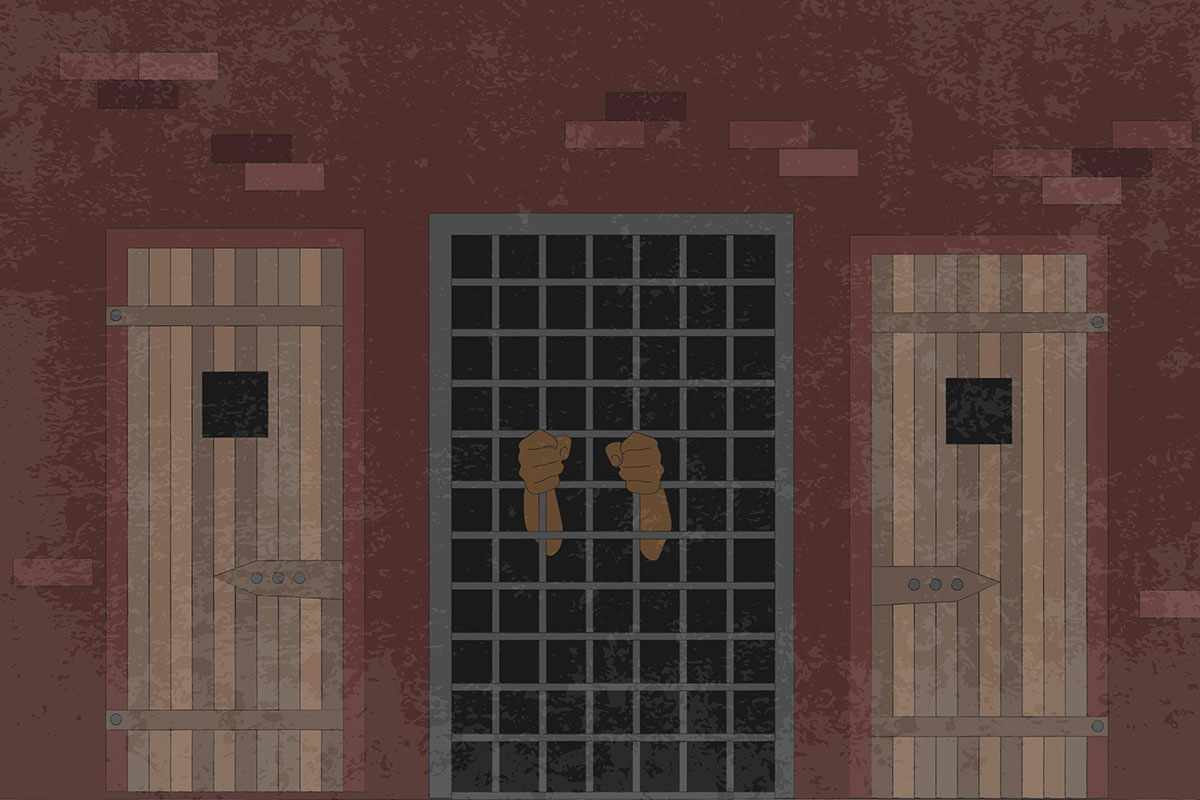

The corner of Seventh and Maryland SW in the mid-1800s and today, showing the Williams Slave Pen and the Orville Wright Federal Building. Illustrations by Samantha Beach Sinagra

In the case of the “Williams Slave Pen,” the voices of the enslaved are scarce but nonetheless potent. The best-known prisoner held in its confines was Solomon Northup, a free Black from Saratoga, New York, who was kidnapped while in D.C. in 1841, and then transported to slavery in Louisiana. We know Northup’s personal history only because he survived the ordeal and wrote a memoir, Twelve Years a Slave, which reached movie screens in 2013—160 years after the book’s publication in 1853.

Northup’s description of the “Williams Slave Pen” is the most detailed extant:

The light admitted through the open door enabled me to observe the room in which I was confined. It was about twelve feet square—the walls of solid masonry. The floor was of heavy plank. There was one small window, crossed with great iron bars, with an outside shutter, securely fastened. An iron-bound door led into an adjoining cell, or vault, wholly destitute of windows, or any means of admitting light. The furniture of the room in which I was, consisted of the wooden bench on which I sat, an old-fashioned, dirty box stove, and besides these, in either cell, there was neither bed, nor blanket, nor any other thing whatever. . . . [Outside was] a yard, surrounded by a brick wall ten or twelve feet high . . . . It was like a farmer’s barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there. . . . Its outside presented only the appearance of a quiet private residence. A stranger looking at it, would never have dreamed of its execrable uses. Strange as it may seem, within plain sight of this same house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol. The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave’s chains, almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol!

Northup’s description of the building’s proximity to official Washington was no exaggeration. During his one term in Congress (1847–1849), Abraham Lincoln lamented that he could see the building “from the windows of the capitol.” Around the same time, Senator Jefferson Davis—who during the Civil War was Lincoln’s opposite as president of the Confederacy—attempted to minimize the obvious horrors of the building, by casually observing, “It is a house by which all must go in order to reach the building of the Smithsonian Institution,” where Davis served on the board of regents.

In May 1855, the abolitionist Henry Wilson addressed the New York Anti-Slavery Society with optimism:

Tis nineteen years since I first stood in the National Capital beside Williams’s slave-pen. There I saw men, women and children chained, and heard their groans. A short time ago I stood on the same spot, but the slave-pen was no longer there; in its place was a garden, and a sign hung there—‘Flowers for sale and boquets [sic] made to order.’ I hope but a few years more shall pass until every spot wherever the groans of human bondage are heard shall be a garden in which the blossoms of freedom shall make glad the eye, and the accents of hope delight the ear.

The “blossoms of freedom” and “accents of hope” did not arrive as quickly as Wilson had imagined; more recent examples of folk history suggest that we are still not there. But the horrific story of the Yellow House and the anniversary of the 1850 Congressional legislation may help us reflect on the tumultuous paths behind us and those that remain still ahead.

Further Reading

Jeff Forret, “The Notorious ‘Yellow House’ That Made Washington, D.C. a Slavery Capital” (2020)

Jeff Forret, “Presidents, Vice Presidents, and Washington’s Most Notorious Slave Pen” (2019)

Jeff Forret, Williams’ Gang: A Notorious Slave Trader and his Cargo of Black Convicts (2020)

Matthew Gilmore, “Jeff Forret: Interview with a Washington, D.C., Author” (2020)

James Deutsch is a curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. He has lived in Washington, D.C., off and on since 1982, and never tires of finding examples of folk history within the city’s boundaries. Intern Levi Bochantin assisted with research for this article.

Samantha Beach Sinagra is a graphic design intern at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She is pursuing her master’s degree at George Mason University in arts management.