In the photographs from my childhood, Thanksgiving looks to me like a Norman Rockwell painting: family gathered around the table, the big turkey as the centerpiece, a highchair parked at one corner, and my father, playing host, perfectly in the moment, brandishing his carving utensils. It wasn’t until a few years ago that my understanding of those moments changed. Undoubtedly, as we settled into our seats to say grace, my father’s thoughts would send him elsewhere, to another, more harrowing time—another set of thank yous.

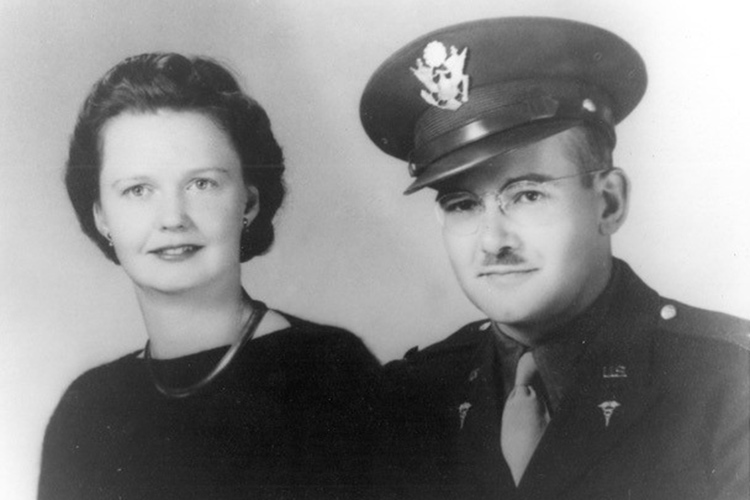

My dad, Captain Durwood J. Smith, was a medical doctor on the Western Front of World War II. But he never talked about it when I was growing up. Instead we discovered his mothballed army uniform in the attic along with other things. We showed up in the kitchen, my brother and sister brandishing the bayonet and dragging the two long swords decorated on the hilt with ruby eyes, while I balanced the outsized Nazi helmet on my child-sized head. Mom immediately confiscated all of it.

“We have to talk to your father about this.”

Over supper, the booty was reviewed and evaluated. Dad fingered the edges of the weapons. Neither the bayonet nor the Nazi ceremonial swords were meant to cut and slice. Given our size and strength, he declared them non-lethal for play. Thus certified as weapons of non-destruction, they were released into our cowboys and Indians toybox arsenal of the 1950s. And then we grew up.

My father died in 1975. My mother never remarried. It was only after she left us in 2015 that we found the letters he had written her from the front. She had saved them all: one letter for each day they were separated, August 1944 through November 1945, 439 numbered letters, each penned in his chicken scratch script.

I read them all, and I transcribed them. I wanted my children to meet the grandfather they never had a chance to know, and I understood that without transcripts, the letters would go unread. I also wanted to acquaint myself with my father as a young man and newlywed, a rookie doctor fighting a war on foreign soil, who missed his life most on the holidays.

This was not the father I had grown up with. My father was the one who picked me up when he came home, enveloping me in the warm comfort of his whisky breath, cigarette smoke, and scratchy cheeks. At bedtime, he would set me on the pot, look at me sternly, and say in his commanding voice, “Now, wee wee.” He was the parent I refused to hear or listen to as I struggled through my teenage years. He was the dad who loved me and expressed pride in my accomplishments; his death had left me bereft on the threshold of my adulthood.

Now I had these letters, written in his hand years before I was born. So there I sat in the evenings, deciphering one letter per day, five per week for three years. I was tempted, but early on I decided not to skip ahead looking for exciting moments and passages, that somehow doing so would cause me to miss his life completely.

I read each letter into a microphone, and used a voice-to-text program to create a document file. I marveled at the software’s accuracy—nearly ninety percent. That said, a final review was essential. With over 400 letters, meeting my goal took perseverance, but each new day and each new letter kept me going. I never skipped ahead. Besides, I already knew the ending—right? Dad came home to become my father.

The letters were filled with the quotidian details of war, and my mother wrote back every day. While I couldn’t read her replies, I could sense in his letters some of the subjects she chose: describing the wartime environment back home and recounting her lonely days as she raised the baby without him. They wrote about money and budgeting, Mom’s living arrangements as she moved between relatives, their imagined future together.

Sometimes they veered off into their physical need for each other, in terms that often made me blush. But, I understood these letters to be the only tangible connection between a man and woman reaching out across the Atlantic to spend a few minutes or hours in the evoked presence of each other.

For secrecy’s sake, there were things he could not write, such as the specific locations where he authored each letter, but through research I was able to coordinate dates and details with allied troop movements. I followed him through Germany and toward Berlin in the spring of 1945. It wasn’t until the German surrender in May that Dad could reveal where he was.

Through the three years of worrying my way along his path, there remain letters that burned their way into my memory word for word. In October 1944, he saw his first real conflict tending to the wounded and dying in the Battle of Aachen; in a letter to his wife describing the battle, he used a kind of wistful poetry of which I would never have expected him capable.Inside Germany

21 Oct 44

Someday perhaps I’ll be able to put down my recollections of this last week for you—I don’t know. It is a jumbled mass of pictures and sounds. Wounds are exceedingly clear— even their anatomical details—the beautiful redness of muscles, and something you’d never think of. In the cold air, open wounds give off a vapor of moisture like you breathe out on a cold frosty day. Most amazing. Another thing which sticks in the mind is the vast miscellanies of articles soldiers carry in their pockets. It’s amazing what you find in them. Anything from cord & knife to a nude Parisienne photograph. And anything between. Someday just for fun I’ll list things I have in mine. It’s wonderful in quality & variety.

Forever, still forms on litters covered with a blanket have funny ways of bobbing up in the memory. I think I know now why men don’t talk much when they come back. Shells coming in give you a cold feeling in the pit of your tummy—just like when you were a kid & went out on some errand into the dark night. You’re sort of scared.

Dad didn’t write about bombs dropping very often, not wanting to say anything that would cause concern at home. This must have been a challenge for someone whose daily task as a medical doctor was to evaluate the damage done by war, to fix what he could and forget what he couldn’t. In this instance, he shared.

By November 1944 my father had moved to an army hospital in a Dutch monastery just across the border from Germany; the Netherlands had been liberated by American troops two months before. His Thanksgiving letter describes the celebration the grateful monks prepared for American troops.Somewhere in Holland

Thurs – 23 Nov 44

Darlyn – here it is Thanksgiving and we’re not together. These damned holidays are the really painful part of this separation. I review where we’ve been & what we've done other holidays – and I am sad. But we’ll be together next Thanksgiving – I hope. And I really believe it will be true.

Today we gave the priests our food – and they fixed our meal, the student priests served it – they did everything for us. It was truly wonderful Sue. At 4 PM dinner was served. They had set up tables in the library. It is a big, beautiful room. About 50’ wide and 150’ long. The ceiling is very high domed affair about 50’ above the floor. The books are in shelves along the wall and there are two balconies about 3½’ wide running all the way around the room. These are reached by a spiral staircase at each end of the room. It looks old – ageless – just as you might guess a monastery library should look like. It was beautiful Sue. Perfectly beautiful. They had decorated it with about 8 flags hung from the first balcony. They had crayon drawings of a G.I., an American woman, a farmer & a big one of a G.I. and a monk shaking hands. They had the tables all set with chairs and silver of their own. The officers had a tablecloth! There was a bottle of beer (quart) and a glass plate & soup dish at each place. We filed in, took our places, said grace & sat! First, we had soup! Served in tureens & ladles. The student priests served us – Officers & Enlisted Men—and did it beautifully. Everything tasted so good.

It was a wonderful meal, beautifully served. They had a music group of 8 voices. As we stood at attention, they sang several selections & then rendered the Star-Spangled Banner & finally the Dutch national anthem. It brought tears to the eyes to see these priests & monks singing the song prohibited for so many years. Their voices were so full of feeling – it was a wonderful, Sue. The music group went up to the top of the spiral stairs, so their songs reverberated through the great vaulted ceiling of the library. Superb! It was almost out of this world. They have a brother – a famous concert pianist of a couple of decades ago – who played throughout the dinner. A regular concert. It was such a wonderful dinner Sue. I wish I could do it justice on paper – but an occasion like that is so perfect that description fails – there is just too much to tell. The menu is enclosed.

Sue, be happy that these beloved “Men of God” out of the greatness of their hearts could give us a memory to carry with us always. They are wonderful Sue. Be grateful that they took care of your husband – and made him, not happy, but so filled with beauty and such a keen sense of gratitude that he forgot for an hour or two his loneliness.

In November 1944, the monks at the Dutch monastery chose to give thanks by preparing a meal for the American soldiers who had come to fight for Europe and the world. In doing so, they offered their guests a respite from reality, a chance to reremember the Thanksgiving dinners of their own individual narratives, celebrated with parents and children, family and friends in the homes they left behind.

It is the alien which delineates our familiar, the foreign that defines our home. Each year, as my family sat down to Thanksgiving dinner, how could my father not return to this other Thanksgiving when so much was at stake and he was so far away? Amid the family babble, the good cheer, he would have revisited the generosity of those men of God who for a short time made him feel warm and safe and somewhere else, and then probably the lonely, frightening months spent in a strange land, fighting a war where the wounded just kept coming.

That Thanksgiving in 1944 belonged in my father’s paper chain of memories, a memory which became part of who he was. Now that memory is a part of me and a part of my family, all because we found his letters to my mother and I was curious. I wish we had talked. I wish I had known.

The identity of each of us is made up of an accretion of memories—memories that tell the story of who we are and where we come from. They define us and, in the larger sense, the traditions of our communities and our country. Particularly in this year, a year many see as disfigured by divisiveness and hate, we should re-envision and celebrate ourselves and our nation as Americans connected paradoxically by our cultural diversity, the hallmark of our national strength and a resource worthy of protection.

Charleen Smith-Riedel is a volunteer in the Rinzler Archives at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Having retired from the tech industry in Seattle, she has picked up on her dated folklore studies, completed at the University of Freiburg, Germany, and is committed to writing on folklife topics for Wikipedia.