Amid ethnic restaurants and idiosyncratic shops on Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia, there’s a storefront called the A-Space Anarchist Community Center. It’s a welcoming space, a meeting place for several activist and community groups, with colorful artwork by local artists on the walls and donated books on tables outside for anyone to take. There is a prison library program, poetry workshops, potlucks, and clothing swaps. And, on some nights, there is very loud religious singing. In the summer, when sound spills from the open doors, passersby who linger more than a few minutes are encouraged to take a copy of The Sacred Harp and sit down to sing shape-note music.

Shape-note singers have been gathering at A-Space every fourth Thursday evening for the past nine years. We sing Christian hymns in a vocal style better fitting a frontier camp meeting in the early 1800s—or a punk show—than a mainline church today. There is no choir director, no audience, and no instrumental accompaniment. The music is loud, raw, rhythmic, and sometimes discordant. The 300-year-old lyrics are powerful, rather than quaint. We’re not a choir or a club (or a cult!), but we are part of a growing, global population of singers—many of them young, singing in this same manner from the same book.

I first came to A-Space nine years ago. Arriving late in a rainstorm, I found myself a book and a rickety chair. About twenty singers crowded into the narrow tin-ceilinged room. They sat in four ranks facing toward a center square. Their singing followed this sequence: a page number was announced and pages were shuffled. A designated person sounded the starting chord. Everyone sang through the song using the syllables fa, sol, la, and mi, followed by a verse or two with words. The person who chose the song stood in the middle of the square to lead the group and moved their arm up and down with the beat, a gesture that was mirrored by many of the seated singers.

This went on for about an hour, and, after a break, another hour, for about thirty songs. Everyone was offered a chance to choose a song and stand in the middle. Some song leaders seemed hesitant, while others led with polished, graceful movements. A number of singers were so familiar with the songs that they hardly looked at the book. I was struck by how focused and serious the group was, though it was evident when we took a break that they could be relaxed and friendly. I was also struck by how young many of them were.

Philly Sacred Harp at A-Space

Video by Rachel Hall

Although the designation “shape note” has come to represent an entire musical genre, it actually refers to the way music is written. Shape-note notation developed from the singing-school movement of the 1700s. The “shapes” are the four symbols fa (triangle), sol (circle), la (rectangle), and mi (diamond), which were designed by a Philadelphia shopkeeper in 1798. They are used to aid in learning vocal parts and replace the round note-heads in standard music notation. This system is related to the do-re-mi, or solfege, method. It is sometimes called “Sacred Harp” after the book we use or “fasola” after the shapes.

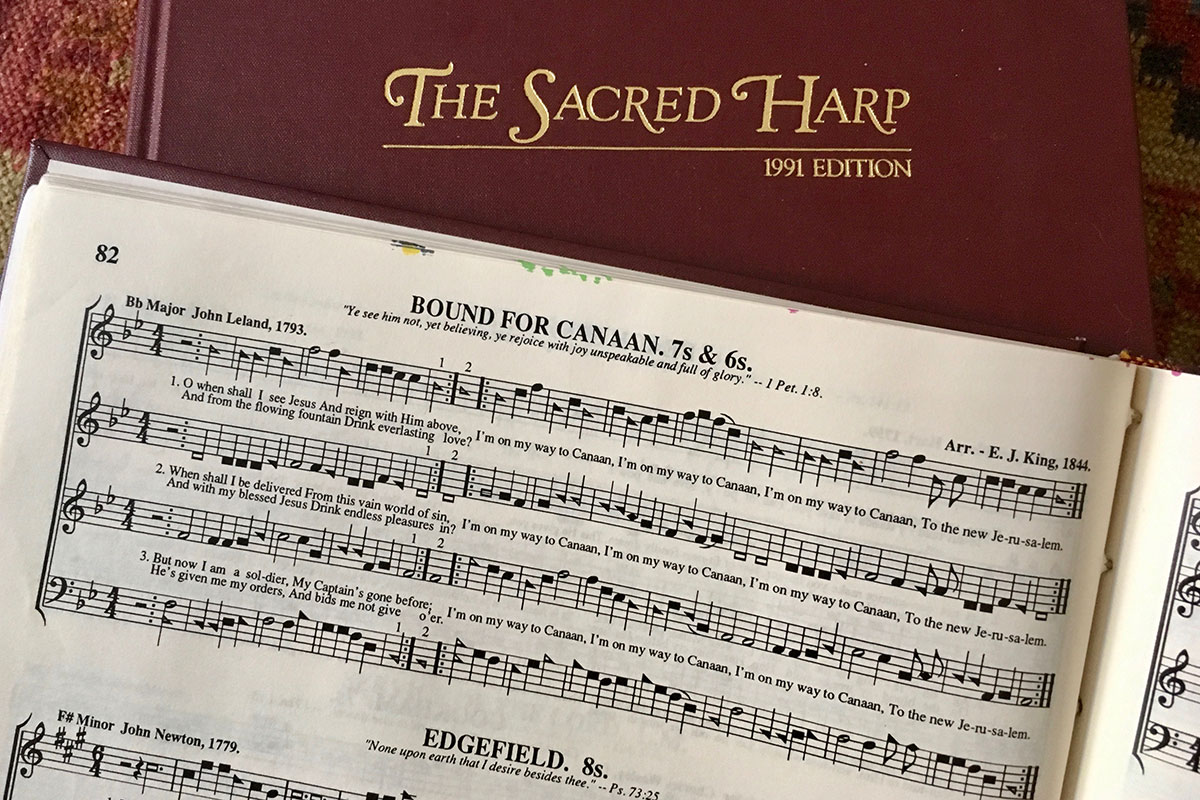

The musical styles most associated with shape-note notation include New England choral music of the late 1700s, Appalachian folk hymns, and camp-meeting spirituals. The Sacred Harp, an eclectic collection of over 500 songs in all these traditions, was first published in Georgia in 1844 and has remained in print since then. Songs are arranged in four voice parts for a cappella singing. However, the parts are not strictly segregated by gender. The melody is carried in the tenor part, which is sung in both high and low octaves, as is the treble part. The other parts, alto and bass, are each sung in one octave. It is difficult to distinguish a single melody in shape-note music, because all the voice parts are melodic in their own right (this makes the music both difficult and fun to sing).

Like the harmonies, the verses we sing are in a style not represented in modern churches. Mortality is a common theme, as in this 1763 lyric from Charles Wesley:

And am I born to die, to lay this body down,

And must my trembling spirit fly, into a world unknown?

and this unflinching look at death:

The coffin, earth, and winding sheet shall soon thy active limbs enclose.

Like the A-Space itself, the lyric “Come ye sinners, poor and needy, weak and wounded, sick and sore” offers an invitation to all, irrespective of circumstance. Another song celebrates, “And we’ll all sing hallelujah, when we arrive at home.” Lyrics like “Oh, you must be a lover of the Lord, or you can’t get to heaven when you die” don’t represent my own beliefs, though I’ll sing them if someone else chooses the song. Although some singers attend religious services, others do not, and not all of us are Christians. Still, it seems that everyone who spends time singing is eventually affected by these words, as I am.

The experience of singing in a group can be intense. Rather than face a choir director or a preacher, we face each other, with the leader of the song in the middle. This can be daunting for a new leader but exhilarating once you have the hang of it. A good leader can choose a song that takes the class to another place, whether musically, spiritually, or emotionally. Regardless of the experience of the leader, the entire group attempts to make every song go as well as possible.

A-Space was not the first place I had sung shape-note music, but it was the first place it took. In the late 1980s, my mother was one of the founders of the Cincinnati Sacred Harp group, and I would go occasionally when I was home from college. At the time, shape-note singing was new to most of us, and learning songs was slow going. We met in each other’s houses. “Beating time”—the arm-waving gesture—was a new thing, and there was some laughter about it. I knew that Southern singers did it, and that I should emulate them because they were the keepers of this living tradition, though I didn’t see the point of it until much later.

The edition of The Sacred Harp used back then was a glorious jumble of songs in different musical styles and typefaces crammed into one book—patchwork produced by the fact that it had been revised a number of times. When a song was removed, another was put in its place. The book also contained peculiar and sometimes funny anecdotes about the songs or their authors, some clearly false. Some lyrics dealing with sin and judgement were uncomfortable for our group of folk musicians and academics. We experimented with changing the words of a few songs. I had the sense of encountering something both very old and very odd.

As I learned later, the shape-note singing revival began in New England in the late 1960s and was characterized by cultural exchange with the South. Singers began to travel to Georgia and Alabama to learn from the masters. Likewise, Southerners took long bus trips north to teach new enthusiasts. Revival communities absorbed not only established musical practices but also how to organize “singings,” events that attract dozens to hundreds of people from near and far. Singings are quite formal, with officers and a minute-taker. New groups also embraced the customs of travel and hospitality that hold the wider community together. Locals are expected to provide a spectacular potluck lunch for an all-day singing and house visitors from far away. There should never be a charge to attend, and we loan books to those who don’t have them.

The desire to incorporate singers outside the South changed the tradition in some ways. In 1991, the Sacred Harp Publishing Company overhauled the entire book and included new songs by composers from the Midwest and New England, as well as the South, while retaining most of the older songs. The book was also redesigned, with the footnotes removed, for a clean, modern look.

Shape-note singing came to southeastern Pennsylvania in the late 1980s. Early groups were similar to my mother’s group in Cincinnati. After a few years, local monthly meetings were established and a number of annual all-day singings began. There are currently about a dozen regular singings every month within two hours’ drive of Philadelphia. Three of these are in or near the city, and the rest in more rural areas. Southeastern Pennsylvania hosts five annual all-day singings and one two-day convention.

2018 Keystone Sacred Harp Convention

Video by Rachel Hall

Although shape-note singing has spread across North America and to several other countries, the basic practice is informed by Southern tradition and varies little among groups. However, there are many regional differences. Popular places to sing in Pennsylvania include 250-year-old Quaker meeting houses, our closest approximation to a Southern country church. The “flavors” of different places are most obvious in their cooking: you’ll find venison in Pennsylvania, bagels in New York City, fresh salmon in Alaska, fried okra in Alabama, quinoa in Massachusetts, and elaborate cakes in Poland. The popularity of songs in The Sacred Harp also changes in different communities.

Philadelphia singers vary in terms of their relationship to the South. Thirty years ago, traveling to Georgia and Alabama was considered the pinnacle of one’s singing experience. This is still true for many singers. Southern singings remain on many “bucket lists,” but few of us visit the South to sing often. We normally travel within a few hours’ drive. Longer trips might just as likely take us to Ireland as Alabama. And not all shape-note singing is from The Sacred Harp. Some of our local groups also sing from The Shenandoah Harmony, a new book assembled by singers from the Mid-Atlantic; there is also renewed interest in related seven-shape traditions.

Given that shape-note singing can be so formal and is tied to conservative Christianity, it’s surprising that it has attracted a generation of young singers, especially in large cities. Although there seem to be as many reasons for singing as there are Philadelphia singers, a few general themes emerge. Primarily, singing offers connection. The customs of travel, hospitality, and reciprocity mean that we form deep friendships with both local singers and those from far away—friendships that transcend serious cultural, religious, and political differences (where else can you find pierced and tattooed city folk rubbing shoulders with plain-dressed Anabaptists?) A number of families with lifelong second- and even third-generation singers have emerged in the course of thirty years. In addition, singing offers, to some, a connection to the past and a pride in perpetuating a living tradition.

The musical practice itself is the main attraction for other singers. The experience of singing loud, rhythmic music face-to-face is powerful—an authentic expression of ourselves. It is completely in the moment. Moreover, shape-note singing provides something of what churches do: an opportunity to connect with spirituality. For some, it is an expression of faith, though not a substitute for church. The ritual of the singing day is close to a religious practice for other singers. Singing together allows us to feel and express our deepest emotions, our joys and sorrows, through music in the company of others.

Many of us come back week after week, cook meals for a crowd, welcome guests into our homes, and drive long distances on the weekends. We seek to create a space where all are welcome, regardless of experience, ability, or means. I see our values, centered on community, spirituality, friends and family, hospitality, travel, a sense of place, and, of course, musical expression, as not dissimilar from the values of generations of singers in the South. What began as an attempt to emulate something “foreign” (to us) has matured into an emergent tradition that feels, at least partly, our own.

Rachel Hall grew up in Cincinnati playing contradance music on piano and concertina. She toured and recorded with the trio Simple Gifts for twenty years and has been singing shape-note music in Philadelphia since 2009. She is one of the co-authors of The Shenandoah Harmony. She is an associate professor of mathematics at Saint Joseph’s University.