Welcome to our language

Taste

The Sauce

—Reesom Haile, Eritrean poet (translation by Charles Cantalupo)

The interview was ending. I was anxious to get on with my day. But the interviewer had one last question for me: “So what is your hope for the future?”

As I pondered the question, it occurred to me that there is something even deeper and more precious to me than the goals I work toward as the director of City Lore, New York’s center for urban folklore. Founded in 1985, we work to preserve places that matter, highlight the work of traditional artists, document stories, bring folk and community-based artists into schools, project poems from the POEMobile, and operate a gallery. Our mission is to further New York City’s—and America’s—living cultural heritage.

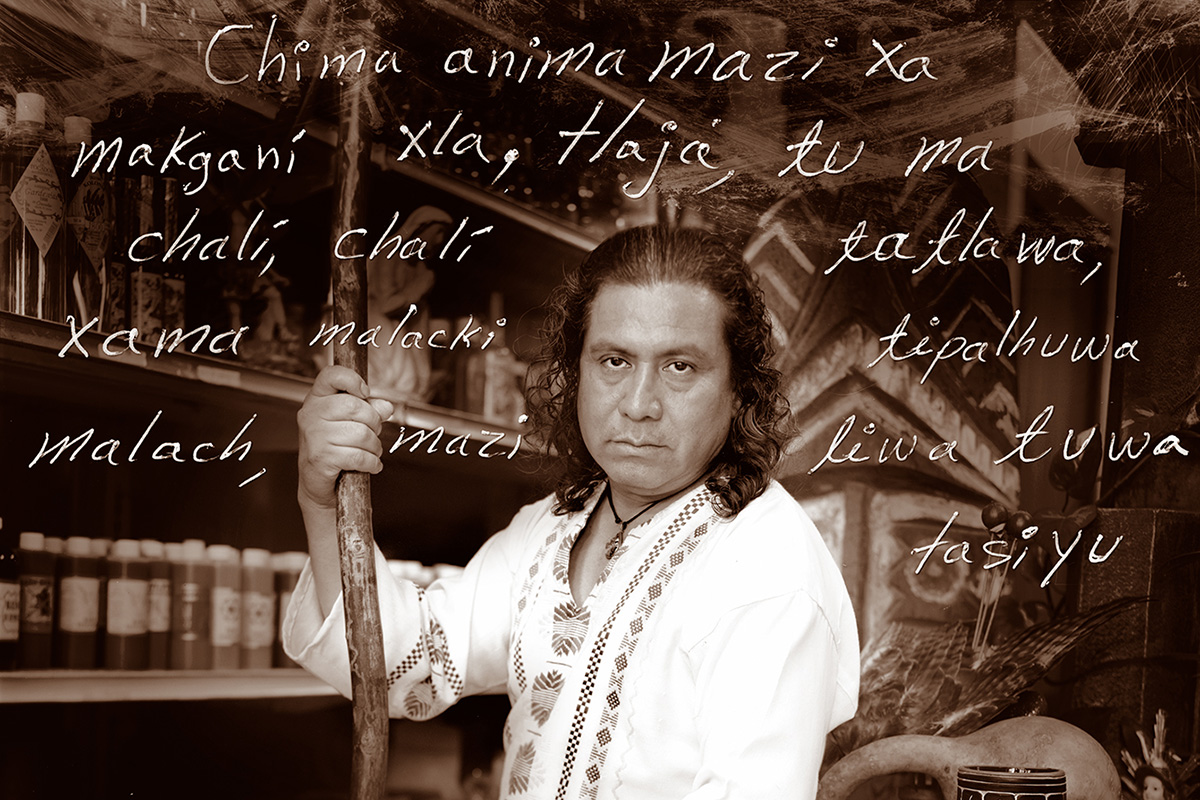

Yet my hope for the future goes beyond this: it is that every soul, whose existence happens to manifest itself on the planet, continues through the generations to bring something new into the world, retains their individuality, develops their own sense of humor, and tells their own unique story in a distinctive way. Indeed, I was inspired to become a folklorist because of the expressions and humor I shared with my brothers. That was our language. As human beings, we rely on our language—the language we live in and in which we feel at home—to fully express ourselves. For each of us to live fully as sentient and distinctive individuals, we need to emerge from a diversity of dialects, languages, and cultures. To explore these ideas more deeply, City Lore has held exhibits such as What We Bring: New Immigrant Gifts and Mother Tongues: Endangered Languages in New York and Beyond. Yuri Marder’s photographs from the latter are featured in this article.

The dissolution of a language diminishes each speaker’s ability to be oneself. Half the languages in the world today will disappear in this century. In New York City alone, the Endangered Language Alliance suggests that many of the more than 600 languages spoken are endangered. The Slovenian and Germanic endangered language, Gottscheerisch, is holding on in Ridgewood, Queens; Himalayan languages are still spoken in parts of Brooklyn and Queens; and the Arawakan Garifuna language can still be heard in the Bronx. For me, there is a global imperative to preserve endangered languages—no matter the scale—whether within a nation, a tribe, or village. As Joseph Albert Elie Joubert from the Abenaki tribe in Quebec province put it, “the secrets of our culture lie hidden within our language.”

But why is preserving endangered languages and cultural diversity as important as, say, climate change, or income inequality? Clearly, they are different issues, but they stem from some of the same causes and harbor the same potential solutions.

Today’s corporations are continually merging into larger and larger entities and increasingly dominating both the global economy and our individual lives with their relentless adherence to the bottom line. Corporations make money by marketing endlessly and ever more effectively to all of us. If they can put you and me in boxes, know what we watch on YouTube, seek to sell us anything we’ve ever Googled, they can customize their marketing to the point where they can determine and shape our tastes sufficiently to nudge us into their market categories. From their perspective, minority languages are simply a hindrance. Capitalism runs on homogenization.

In this new world era, governments are viewed as corporations (small ones at that), and we the people not as citizens but consumers. The nuances of art threaten to become simply “content” produced by “creatives” for large corporate entities. Racial and gender parity, issues of social justice and language diversity, are hardly priorities.

The same corporate network in consort with government entities find it profitable to cut down forests and corporatize farming, forcing many small farmers who are speakers of endangered languages into cities where it is more difficult to get along in their native language. Most corporations refuse to risk profits by addressing climate change, contributing to deforestation and the dissolution of isolated communities needed to keep endangered languages vital. It is easier for them to market their products in majority languages. As Nora Marks Dauenhauer, a Tlingit poet writes,

Trapped voices

Frozen

under sea ice of English, buckles

surging to be heard.

Endangered languages are, in the words of Irish poet Gearóid Mac Lochlainn, “teanga i mála an fhuadaitheora”—the tongue in the kidnapper’s sack.

“Against this threat, a global cohort of language warriors are mobilizing,” linguist K. David Harrison writes. “They are speaking, texting, and publishing in Hawaiian, Koro, Kallawaya, Siletz, and Garifuna. Thousands of tongues previously heard only locally are now—via the internet—raising their voices to a global audience. We can all help to raise awareness of the value of language diversity, and contribute to revitalization efforts. Language rights are, after all, human rights. And the knowledge base found in smaller languages sustains us all in ways we may not even perceive.”

The Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, City Lore, and Bowery Arts + Science (the Bowery Poetry Club) down the street from us have devised a series of programs to protest the rising tide washing away so much history and culture through the erosion of linguistic diversity. In 2006, City Lore and Bowery worked with poet Catherine Fletcher to sponsor a special iteration of our People’s Poetry Gathering, focusing on poetry from endangered languages. We issued, along with poet Jerome Rothenberg, a Declaration of Poetic Rights and Values. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all languages are created equal, endowed by their creators with certain inalienable meanings.”

In 2009, City Lore began working with Bowery on the short film Khonsay: Poem of Many Tongues. Directed by Bob Holman, Khonsay is a tribute and call to action to support the diversity of the world’s languages. The term खोनसाइ, Khonsay, is written in the Devanagari alphabet used in the Boro language of India. It means “to pick up something with care,” as it is scarce or rare. Our poem is a cento, a collage poem; the name in Latin means “stitched together,” like a quilt. Each line of the poem is spoken by the speaker of a different endangered or minority language. The printed form of Khonsay was featured on panels at the 2013 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

That year, the Festival’s One World, Many Voices: Endangered Languages and Cultural Heritage program highlighted language diversity as a vital part of our human heritage. Cultural experts from communities around the world attended to demonstrate how their ancestral tongues embody cultural knowledge, identity, values, technologies, and arts.

Festival visitors interacted with Kalmyk epic singers and Tuvan stone carvers from Russia, Koro rice farmers from India, Passamaquoddy basket makers from Maine, Kallawaya medicinal healers and textile artists from Bolivia, Garifuna drummers and dancers from Los Angeles and New York, and many others. These performances underscored how the disappearance of a language threatens unique ways of knowing, understanding, and experiencing the world.

Following the Festival program, co-curator Marjorie Hunt collaborated with Esri, a geographic information mapping company, on an endangered languages story map. The interactive map introduces users to speakers of endangered languages from around the world and learn what they are doing to save their languages.

Other important initiatives include Language Matters, a PBS documentary which focuses upon the rapid extinction of many of planet Earth’s human languages and the multifarious struggles and efforts to save and preserve them; the Smithsonian’s annual Mother Tongue Film Festival; and the Smithsonian’s SMiLE project: Sustaining Minoritized Languages in Europe.

Earl Shorris writes, “There are nine different words for the color blue in the Spanish Maya dictionary, but just three Spanish translations, leaving six [blue] butterflies that can be seen only by the Maya, proving that when a language dies six butterflies disappear from the consciousness of the earth.”

We don’t want to lose those six butterflies.

My hope for the future is bound up with language and cultural diversity. Our individuality lives in language. Is that more important than world peace? Perhaps not. Yet, if the planet ever does become a “peaceable kingdom,” here’s hoping that it comes about not because we have been corporatized into sameness but because we have learned to communicate across differences.

Steve Zeitlin is the founding director of City Lore. His latest book is The Poetry of Everyday Life: Storytelling and the Art of Awareness.