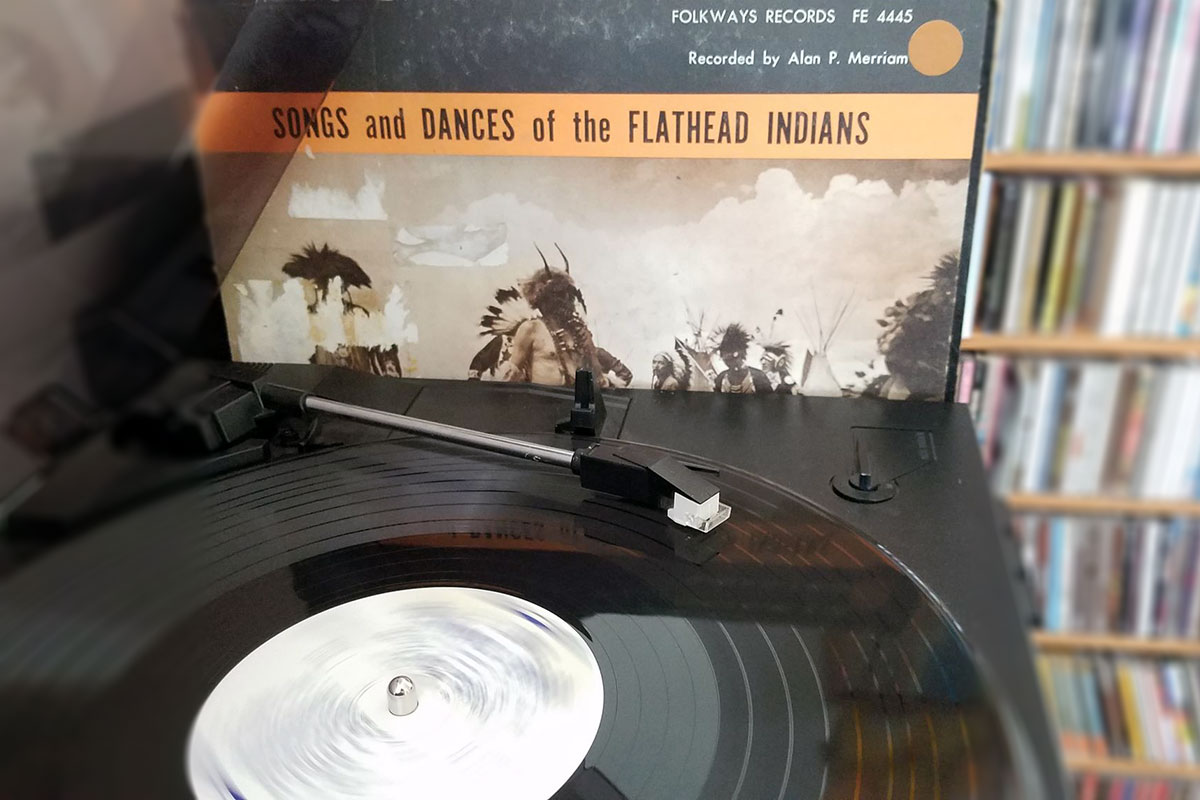

You select an album in the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings catalog, and your room is flushed with the sounds of “native” drums and flutes. But that’s all you know about the song, and that’s nearly all there is to know. You enter into a music world, naive of the history and culture it represents because only limited information is available.

What does this mean for Smithsonian Folkways? How did this happen, and how can it be prevented in the future?

In October 2019, Robert Leopold, deputy director for research and collections, wrote “What is Shared Stewardship? New Guidelines for Ethical Archiving” to highlight the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage’s commitment to shared stewardship. Leopold explained the policy: “Shared stewardship (sometimes called ‘co-curation’) refers to sharing authority, expertise, and responsibility for the respectful attribution, documentation, interpretation, display, care, storage, public access, and disposition of a collection item with the advice of the source community.”

A definition is one thing. Putting it into practice is another.

There are more than 4,000 accessible Indigenous tracks from around the world within the Folkways catalog. Some date to the 1930s, when anthropological approaches to ethnography were less culturally sensitive. Many of those who recorded the tracks are no longer around to provide context and lend additional insight. This prompts several questions: how many of these albums were collected under misguided pretenses? Furthermore, how many hold sacred, secret, or personal content that should not be heard by just anyone with a link? How can we, as anthropologists and curators, identify sensitive content? And how many lack artist names or the cultural recognition they are entitled to?

We engaged with these questions during our summer internship in the hopes of gaining a deeper understanding of the collection.

Definitions of ethical standards are subjective in many such cases, as the practices of ethnography and acquisition of recordings evolved rapidly within the fields of anthropology and archival studies. At ethnomusicology’s inception in the late nineteenth century, recordists set out to preserve what they believed were dying cultures—a very progressive initiative for the time. Music executives, such as Folkways founder Moses Asch, operated on trust in individual relationships between the recordist and artist to produce albums. As a result, the recordist or the compiler produced albums with whatever level of detail they deemed useful in the liner notes.

These processes of production reflected musicological practices of the time which focused on in-depth descriptions of music, written as forms of scientific data, in order to measure a community’s “development” in relation to the Western world. During this era, comparative musicologists analyzed certain musical characteristics, such as elements of composition, for complexity and style. By comparing them to the progress of western-style music, the musicologists deemed certain tracks “primitive” or at an earlier “stage” of development. More often than not, they did not document the names of artists in favor of looking at composition over culture.

The organization of the Folkways music collection began with a fixation on a new way of presenting albums as singular artworks that spoke for themselves in a conscious effort to remove Folkways from participating in comparative musicology. Slowly, over time, liner notes started to change by focusing on music as an informed cultural creation, which subsequently provided more detail and context about performers. There is an undeniable shift in academic thinking, brought forward by curatorial efforts and dedicated individuals both at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and in the Smithsonian community at large, but the albums have not been expressed to their fullest potential.

We are both students of Indigenous philosophy, formally trained in Aboriginal Australian and Native American history and cultural heritage. As non-Indigenous researchers ourselves, we began with a modern concept of how collectors and curators can contribute and collaborate with Indigenous communities—one that emphasizes the difference between custodianship and appropriation. It is our hope within Folkways to help reawaken the dialogue or, perhaps more importantly, to critique the relationship between archival custody and ownership of intellectual property.

When we started this project, we found the precedents set by Folkways promising in terms of the dedication to ethnomusicology and ethics but also discouraging in terms of the precedents set for identifying sensitive material.

For example, in 1982 Folkways Records released the album Dabuyabarugu: Inside the Temple - Sacred Music of the Garifuna of Belize, recorded and produced by Carol and Travis Jenkins. This album is one sample of the materials we focused on auditing this summer to improve the collection and implement standards of shared stewardship. By diving into the metadata and combing through album liner notes, we identified more than fifty artists who had been lost in the details of thousands of liner notes, flagged derogatory language, and created a plan to rectify permissions issues.

Dabuyabarugu stood out immediately; the title itself references the non-secular nature of the material. Upon further inspection, we found deeper issues. Of the sixteen tracks on the album, only one references the artists by name. Even after comparing the metadata to the liner notes, no additional information could fill the gap in artist acknowledgement. Moreover, the permission to publish sensitive and sacred songs is ambiguous.

Another album that caught our attention was The Bora of the Pascoe River: Cape York Peninsula, Northeast Australia, recorded and produced by Wolfgang Laade in 1963 and released by Folkways in 1975. The album is a collection of songs and stories from the Lockhart River Mission on Cape York that includes sacred initiation practices involving the Bora rings that are traditionally accessible only to initiated men in the community. We lacked confidence that the recordist received permission to publish and sell these tracks to a larger audience.

While investigating these ambiguities and rectifying deeper issues with the albums, we created an outline of concrete steps to implement the values of shared stewardship. For example, additional research focusing on field notes and correspondence of the recorders and compilers is invaluable for finding the names of artists. Field notes are instrumental for understanding sacred, secret, or personal content within the communities in question. Outreach to experts and Indigenous communities is necessary to define and refine what is deemed sensitive material. Nuanced understanding of cultural sensitivity comes from experience. Without our own background in Australian Aboriginal philosophy, we would not have understood how the Bora rings are a sensitive subject.

Our project aims to shed light on albums such as the ones above to ensure that sensitive information is respected and shared responsibly. Shared stewardship begins with recognizing potential problems or insufficiencies in the collections at hand and deciding to pursue proactive solutions. With the fervor of the Black Lives Matter Movement taking hold, it seems only right for us—and the institution as a whole—to work on uplifting and protecting BIPOC artistic expression. We live in a time of nationwide self-reflection to revise precedents that have perpetuated white supremacist structures of power. Recent pivotal moments that challenge the existing system include issues of land rights, such as the Muscogee case in Oklahoma that granted the tribe native sovereignty over half of eastern Oklahoma, and the California city of Eureka returning more than 200 acres of land to the Wiyot Peoples in October 2019.

Half the battle is recognizing injustice and systemic imbalance; the true merit lies in taking action to create change. Giving Indigenous performers and communities the clear ability to control or refine sensitive materials should be a priority. Censorship is not always born of action; it is also born from inaction.

There are differing expectations of what shared stewardship will look like when put into effect. The discourse within the Smithsonian often tangles itself in questions of royalties associated with outreach to Indigenous communities. Even a nonprofit record label like Smithsonian Folkways cannot ignore financial concerns. That said, the cultural value of an album is never placed below monetary value. Understanding the role of business in the process of museum curation is vital to the implementation of shared stewardship to ensure money does not dominate the conversation.

Moreover, a uniform plan of action does not suit all tracks and albums. As cultural property, they must be handled on a case-by-case basis to consider the special needs of the artist and community.

A clear generational gap—not of age but of institutional leadership—has emerged in the approach of scholars to shared stewardship and cultural intellectual property. We noticed in our research that problems begin with waiting for others to come forward and ask for change rather than actively creating a system of outreach to Indigenous communities in a thoughtful and methodical way. Further, the very definition of shared stewardship emphasizes co-curation. There is no hiding the lack of Indigenous representation on the management side of this project. As Mali Obomsawin “This Land Is Whose Land? Indian Country and the Shortcomings of Settler Protest,” “The means of allyship—and dismantling culturally systemic ignorance—starts with ‘passing the mic’ to marginalized people, who know our communities’ experiences, needs, and struggles better than anyone else.”

The creation of positive, ethical, and systematic change begins with conversation but is brought to fruition through substantial planning that may rectify past precedents. Although the shift will be neither simple nor overnight, we believe that the creation of new ways of thinking about activism and redefining waiting as a form of complacency is essential to paving the way for true collaboration with Indigenous artists and scholars.

These are complicated ideas, and the question remains: who is going to pass the mic?

Iris Bennett is an intern at Smithsonian Folkways and a senior at Oberlin College studying anthropology and creative writing. As a student curator, she is working on a collaborative exhibit for Oberlin’s Alaska Native collection. Her interests will always, one way or another, align with art, nature, design, and culture.

Haley Gallagher is an intern at Smithsonian Folkways and a senior at American University studying anthropology. Her interests are cultural heritage and material anthropology, as well as sharing a well-told story. This summer she began an ethnographic research project creating portraits of those experiencing homelessness in D.C. and will continue to do so into spring 2021.