Once a major source for humor and satire in newspapers and magazines, cartoons still appear in nearly all languages worldwide, though they are more likely found on the internet than in a diminished print media. Known for being cute or funny, they typically produce a chuckle, or bring a satiric twist to the seriousness of the headlines. But the harmless cartoon also has an evil twin that, for a fairly large part of their history, injected a nasty, racist element which libeled entire communities.

In fact, the ways in which some nineteenth-century American cartoonists conceived of minorities was anything but funny. From “thick-lipped, nappy-headed” African Americans, to “drunken” Irishmen, to “hook-nosed, curly-headed, money-hungry” Jews, to “crafty, slant-eyed” Asians, American cartoonists mined the ugliest of stereotypes to slander ethnic minorities under the guise of comedy.

By the early twentieth century, these visual attacks had become common fare in American popular culture, found in a diverse array of ostensibly innocuous media, ranging from newspapers and magazines, joke books, postcards, and sheet music, among other kinds of popular products. This kind of ethnic caricature was standard practice in cartooning, and even famous cartoonists engaged in the practice. Intended to be funny, they are actually hardcore examples of cultural othering. On one hand, they can be seen today as part of a vulgar and hateful visual lexicon that is no longer part of civilized discourse. On the other, they serve as a warning to think twice when it comes to comic representations of minorities.

The rise of racial and ethnic caricature took place during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the same period which saw millions of immigrants arrive on American shores. Each major immigrant group, in addition to African Americans—who bore the worst of it—served as fodder for the American comedy industry. Difference, whether cultural, linguistic, or physical, was seen as a rich vein to mine in the ore of comedy. Cartoons, a visual form instantly readable by anyone, even without language, helped promote racial and ethnic stereotypes in a comic medium, making them seem not only innocuous, but also acceptable—and even fun.

It was in this cultural atmosphere that between 1880 and 1924, two million mostly impoverished Jewish immigrants arrived in America. Even before they stepped off the boats, they were othered: there was already a hateful industry of anti-Jewish caricature in Europe that became widespread internationally, a result of a growing periodical press. Picking up on this, popular American humor magazines like Puck and Judge caricatured these immigrants using preexisting visual tropes: large hooked noses, curly black hair, and stooped posture. If that wasn’t sufficient, American cartoonists also latched onto cultural stereotypes of the greedy, deceitful, and, miserly Jew. What a welcome to America!

It’s difficult to say whether most Jewish immigrants ever saw the ways in which they were portrayed in the pages of America’s newspapers and magazines. They were more apt to read newspapers in their own language: Yiddish. From the 1880s through the 1930s, the Yiddish press grew from a few small weeklies to a huge industry that produced up to five daily newspapers in New York City alone (and many others throughout the country) with a circulation that rivaled that of the English-language press.

But when the American Yiddish press first appeared in the early 1870s, it was poorly funded and took time to professionalize. Though mass-circulation newspapers were an entirely new phenomenon in Jewish life—only one had been permitted in the Russian Empire, which held the world’s largest Jewish community during the nineteenth century—America’s Yiddish readers took to them fairly quickly.

The Jewish people have a 3,000-year-long relationship with the written word, but until the modern era, pictures appeared in Jewish texts only infrequently. Yiddish editors, however, kept watch on their industry and began to imitate aspects of the English-language press, including the frequent inclusion of images in the body of the newspapers, a feature that had become relatively common in American newspapers in the years that followed the Civil War.

As these Yiddish papers began to succeed, editors began to include images, which, initially, were made from engraving plates they found at the printer and reused. Yiddish editors didn’t express much interest in paying artists to create either engravings or other drawings for the few Yiddish papers that existed in the 1870s and early 1880s, and they continued to use preprinted pictures.

Most of these repurposed images were of well-known political figures. Cartoons, ever-present elsewhere, had never appeared in Yiddish, probably because the relationship between Jews and cartoons was extremely unpleasant. Jews who could read languages other than Yiddish were doubtlessly familiar with racist caricatures of them that appeared in newspapers and magazines in English and other European languages. If Yiddish editors wanted cartoons in their papers, they would have to reassess how to present Jews in caricature. Or would they?

The year 1881 marked the beginning of a mass emigration of Jews from Eastern Europe. In the United States, industry was booming. Leaving behind economic hardship and political oppression, as well as violent pogroms, Jews flooded into New York’s Lower East Side, creating a much larger readership for the city’s Yiddish press. The publishers of the most successful Yiddish paper at the time, a weekly called Yidishe gazetn, founded in 1876, saw their readership rise. By 1885, they were geared up to start the world’s first Yiddish daily.

Originally a simple, four-column, four-page folded sheet, Yidishe gazetn shared no images with readers, but after a few years, they began to print repurposed images. However, original art, drawn by and for a Jewish audience, was a ways off.

By the mid-1880s, cartoons were central features of humor magazines. Newsstands, where most people then availed themselves of their quotidian reading material, were dripping with dailies, weeklies, and monthlies, many of which had become much more compelling visually as publishers came to understand that images attracted readers. And cartoons all the more so.

With their industry printing pictures left and right, the publishers of Yidishe gazetn decided to include a few small images in a special Passover supplement they published in the spring of 1884. Maintaining their practice of simply using what was already available, the images and the cartoon they used had been previously printed in other magazines.

But the truly bizarre thing is that cartoon they chose to publish—the first-ever in a Yiddish newspaper—was blatantly anti-Semitic.

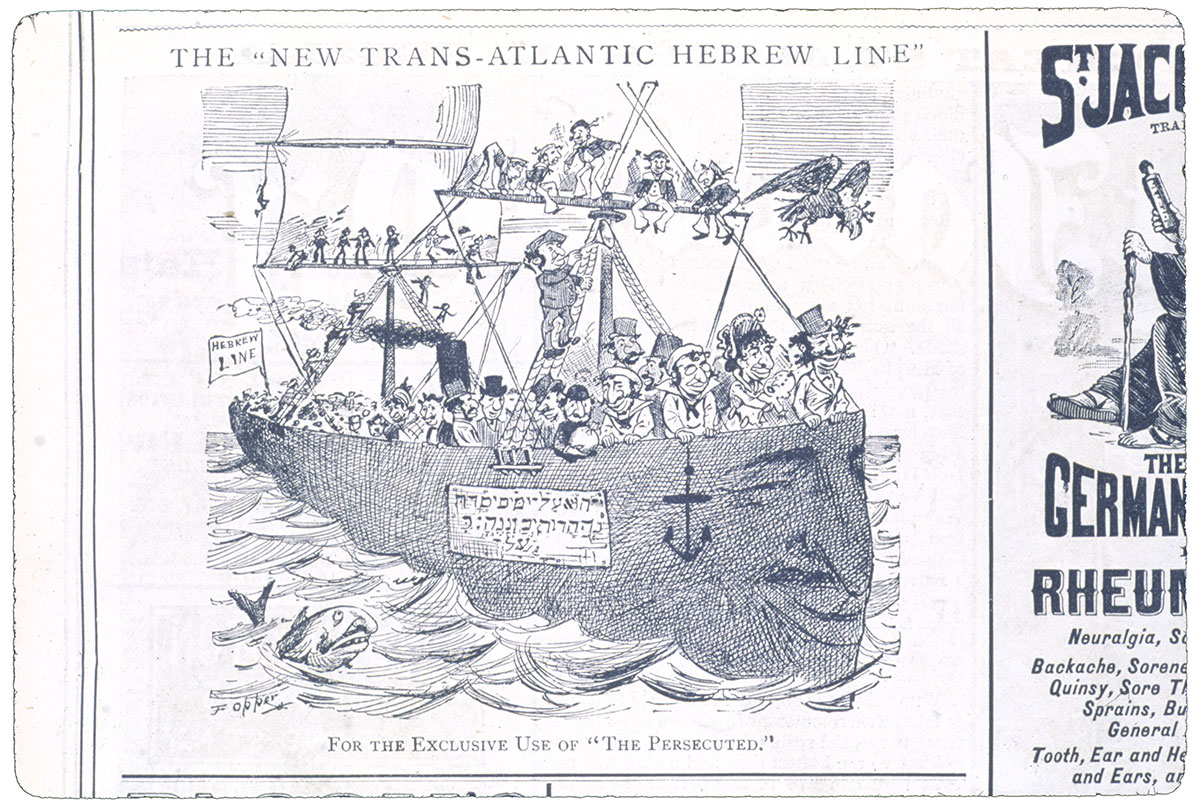

Created by leading American cartoonist Frederick Opper at the beginning of a large wave of Jewish immigration from the Russian Empire, the cartoon purports to show a ship full of Jews emigrating to America. Having originally appeared in the popular humor weekly Puck, the caption reads, “For the exclusive use of ‘The Persecuted,’” as if Tsarist persecution of the Jews was not a known reality. Moreover, Opper appears to convey the Jews look reasonably comfortable, exploiting a false victimhood in order to gain entrance into the country. Engaging the standard Jewish caricature—curly black hair, thick lips, and big noses—Opper also creates a kind of Jewish universe, where not only are all the passengers and crew Jewish, but so too are the fish in the water, as well as the face on the bow of the boat. Ironically, some of these features would also become useful when Yidishe gazetn decided to turn it into a Yiddish cartoon.

Clearly, this was a strange editorial choice. In engaging the cartoon form for their humorous Passover supplement, the editors of Yidishe gazetn showed no qualms in printing the dark-haired, hook-nosed, thick-lipped caricatures. They did mitigate the anti-Jewish meaning of the cartoon by removing the offensive text and replacing it with “Next Year in Jerusalem” (the final line of the Passover Haggada) and “Direct to Palestina.”

But together with the Jews’ faces, the new pro-Jewish thematic created an odd dissonance between image and text wherein an image with the outsider’s vision of uncomplimentary “Jewish” physical characteristics was combined with a comic, pro-Jewish, proto-Zionist text. How readers reacted to this is anyone’s guess. One clue may be that Yidishe gazetn would not print another cartoon for decades and then only infrequently.

But a growing number of Yiddish press outlets across the United States and throughout the world did begin to experiment with cartoons, and by the first decade of the twentieth century they were a common feature. Although their initial appropriation of Opper’s immigration cartoon is a strange one, it was only the first dip in cartoon waters for the Yiddish press. It reflects a desire to participate in the developing visual technologies they saw in their industries, but it reveals an odd complacency and resigned acceptance with regard to negative images of Jews. Because the cartoon genre was new to them, they may have naively accepted the style of caricature as a naturally occurring phenomenon. After all, negative ethnic and racial caricature was ubiquitous at the time. But another idea comes to mind. As Yidishe gazetn was a Yiddish publication, the editors may have sensed that Jews making fun of other Jews was acceptable. While this may have been acceptable in the context of the period, readers today would find the image horrendous.

Yiddish magazines and newspapers would eventually come to include original cartoons as a regular feature, beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century. Cartoonists in the Yiddish press would come to draw thousands of cartoon Jews that, although to a lesser degree, still embraced ethnic caricature, i.e., many of the Jews they drew still had dark hair and big noses.

But these images, which ranged from critical political and social cartoons to silly comic strips, appeared within the context of the Yiddish press, which was a thoroughly pro-Jewish enterprise and thus hardly anti-Semitic. They can, as such, be considered part of the long Jewish tradition of humoristic self-denigration, wrapped up in a tacit and temporary acceptance of the outsider’s view. Or, more succinctly, anything for a laugh.

Eddy Portnoy is academic adviser and director of exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, as well as the author of Bad Rabbi and Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford University Press 2017). For nearly a century, YIVO has pioneered new forms of Jewish scholarship, research, education, and cultural expression. The YIVO Archives contains more than 23 million original items, and YIVO’s Library has over 400,000 volumes—the single largest resource for such study in the world.