In 1980, anthropologist Robert Sayers and associate Gary Floyd journeyed south in a big truck. Their instructions? To pick up pottery and other folk art for the 1981 Festival of American Folklife.

According to Sayers, whom I interviewed in fall 2022, the organizers of the event (now the Smithsonian Folklife Festival) had selected artists to contribute pieces for the Festival Marketplace and invited the artists to “make one very extra special piece” for an auction tent. Burlon Craig was one such artist on their itinerary, and his “extra special” extra-large face jugs, along with other non-auction items, found their way onto the truck.

Born in 1914, Burlon Craig did not descend from a family of potters like others in the North Carolina region. Instead, in exchange for chopping wood, he learned the trade as a young teen from a neighbor, James Lynn, who taught him the distinctive style of pottery made in the Catawba Valley. Pottery then became a passion even as Craig continued farming.

Craig found himself immersed in Catawba Valley pottery, a regional art form defined by two techniques: the use of alkaline glazes, which combine ashes, crushed glass, and clay slip, and the use of a “groundhog kiln,” named for its underground construction, to fire the jugs and pots. The long, narrow passageway of the kiln ends in a chimney that extends above ground. To load it, potters crawl into the structure and pass the pots into the space, lining them up on narrow wooden boards. To fire, the kiln requires an ample amount of wood, reaching over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Both the kilns and the alkaline glazes predate the Catawba Valley, originating in China almost 2,000 years ago. There, artists used “dragon kilns”—similar in shape to the groundhog kilns—to fire ash-glazed pots. While alkaline glazes are common to East Asia, in the United States they were traditionally found only in the South. Historians theorize that a merchant-ship captain in Charleston disseminated the knowledge around 1800, but because the glaze materials are so common and the formula unsophisticated, connections to Asia may be coincidental.

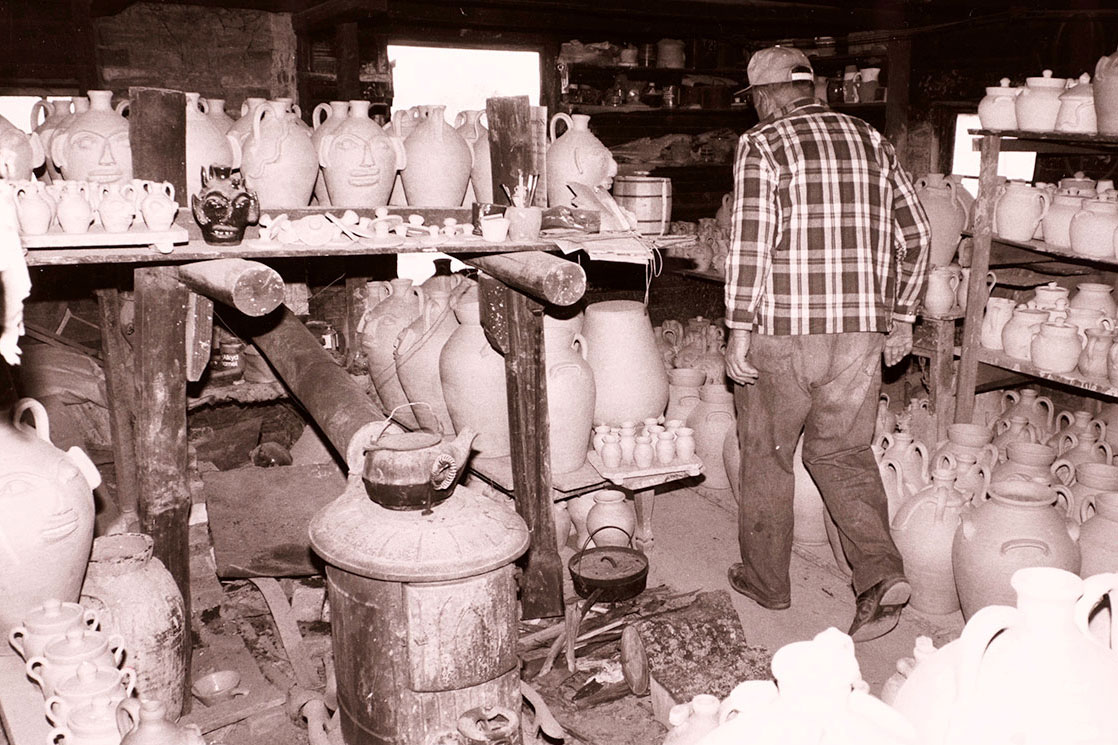

Craig returned to Vale, North Carolina, after serving in World War II, and he bought the shop building and kiln of Harvey Reinhardt, a prominent potter in the area. Still used by Craig’s family, this groundhog kiln is the oldest continually running kiln of its kind. Much of Craig’s materials and equipment, including the wheels and glaze mill, also came from local potters.

But the technique—that isn’t as easily borrowed or bought. Craig described learning to throw pots, or “turn” as he calls it, to a PBS interviewer: “Well, nobody done teach you to do this. You got to do it yourself. You got to get your hands in the mud.”

He never stopped learning and experimenting. Each time he fired the kiln, which stores around 500 pieces, Craig dedicated half a dozen to experimentation, whether that be through glazes or decoration.

“You have to have a market for what you make,” Craig claimed, and experimentation was one way to discover what sold. Initially, that “market” appreciated utilitarian wares, such as churns and jugs that could store milk and other necessities. With technological advancements, such as refrigeration and mass-manufactured glass bottles, that market declined. This shift happened later in the South than in the North, but a separate tourist market nevertheless became interested in the decorative styles.

Later in his career, Craig’s better-selling works were his face jugs, decorative and functional containers with expressive facial features on the sides. He also became popular for his “swirlware,” jugs and pots using various colors of clay in a swirling pattern.

A Catawba Valley potter fortuitously conceived swirlware in the 1920s, and others, like Craig, replicated its style because of its popularity. To create the swirl effect, Craig layered two clays of different colors before turning the double face jug. Speaking with folklorist Charles Zug,Craig speculated,“I don’t think any of them really liked to make [swirlware],” because of the extra time involved, “but it would sell.” The profit made the additional effort worth the while.

When asked about the beginnings of face jugs, Craig told PBS, “it originated in Africa… they made them… as ugly as they could…and put them on their graves, to keep the evil spirits away from… their loved ones.”

Historians trace face jugs to Africa, and a group of enslaved people in Edgefield, South Carolina, popularized the practice in the United States. “They made them… as ugly as they could,” Craig told PBS, “and put them on their graves to keep the evil spirits away.” The use of kaolin, or “china clay” mineral, also connected the two continents. In west-central Africa, ritual experts activated minkisi—anthropomorphic sculptures believed to house spiritual entities—by inserting kaolin. The same mineral deposits were found in the southeastern United States, and many face jugs contained kaolin. This might explain why face jugs were so limited regionally.

While Craig recognized the legacy of the face jugs, this was not what drove him to them. According to Zug, Craig did not like decorating face jugs, but he approved of their “modern efficiency.” Face jugs earned higher profits without taking up additional kiln space, so the practice, as with swirlware, resulted from profits more than passion.

Despite not knowing Burlon Craig prior to his trip south, Bob Sayers purchased and owns some of Craig’s work. He “just made the most beautiful pottery,” Sayers confessed. Sayers, of course, was not the only one interested in a Burlon Craig jug. Craig had already become well known in the 1970s, but after the 1981 Folklife Festival, he became so popular that he and his wife Irene, who helped with some decorating and the kiln unloading, took special precautions.

“When they unload[ed] the kiln, they put a big rope around” all of the pottery since “all the pottery collectors are just waiting for that moment,” Sayers said.

In the years following the Festival, the couple handed out draw numbers, like tickets at a deli counter, to create some semblance of order when selecting the jugs. Craig’s popularity came mostly from word of mouth, but his involvement with the Festival also heavily increased his sales. When asked why people come to Craig’s kiln unloadings, one woman told PBS it was because his work “had a display in the Smithsonian.” Others had collected upward of 200 Craig jugs over decades.

By the 1980s, Craig was one of the last potters to continue the traditions of the area. When PBS asked if he saw the traditional Catawba Valley pottery coming back, he replied, “I see a lot of interest in it. I don’t know. I don’t think it’ll ever come back like I’m doing it… but there’s a lot of people interested in making pottery now.” He received the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1984, and his rising fame sparked interest in Catawba Valley pottery. He worked up until four days before his death, turning face jugs and other pieces. Craig passed away in 2002, and he received a eulogy from his researcher and friend Charles Zug.

In 2008, the Reinhardt-Craig House, Kiln and Pottery Shop entered the National Register of Historic Places. Under the statement of significance, the house, kiln, and pottery are associated with notable historical events, architecture that embodies a particular period, and a person, Burlon Craig, who was consequential as well. This designation is testament to Craig’s work, unintentionally and intentionally, to revitalize a historic folk-art tradition in his community.

Today, the Catawba Valley boasts a small group of potters who follow in Craig’s footsteps. He mentored some, such as Kim Ellington and Charles Lisk, and the second and third generation of the Craig potters continue his practice as well. Craig’s son Don and grandson Dwayne both create more artistic pieces than their predecessor. They focus on the uniqueness of the product for a market that is more educated and more inclined to purchase artistic pottery than they were when Burlon was turning face jugs.

The Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society in North Carolina, founded in 1988, hosts auctions of Southern pottery, and some of Craig’s wares are included in the 2022 auction catalog. Their mission, like Craig’s unintentional one, is to combat the disappearing folk potting foundations. Despite viewing himself humbly as an “an old farmer that makes some pottery,” Craig’s legacy remains in the annual Catawba Valley Pottery and Antiques Festival and in his many jugs scattered nationwide.

Rylyn Monahan is a former intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a senior art history major at Carleton College.