Each year at Easter, my family in Western New York continues our longstanding routine. The night before, on Holy Saturday, we dress up in nice clothes and drive to the church, even though it is located just a few short blocks away. There, our grandmother joins us for the Easter Vigil Mass.

On the day of, I wake early—earlier than my younger sister, anyway—to the sun shining through the sheer curtains of my room, washing away the aches of another frigid Buffalo winter.

Easter morning is full of adventure, competing with my sister over who can find colorful plastic eggs and our baskets full of traditional sweets, like Cadbury Creme Eggs and jellybeans, personalized trinkets, and chocolate rabbits and sponge candy from local chocolatiers. By afternoon, my family journeys from one suburb to the next toward my grandma’s house. By the time we arrive, she is finished warming our Easter feast and seeking our aid to lay it out in the dining room.

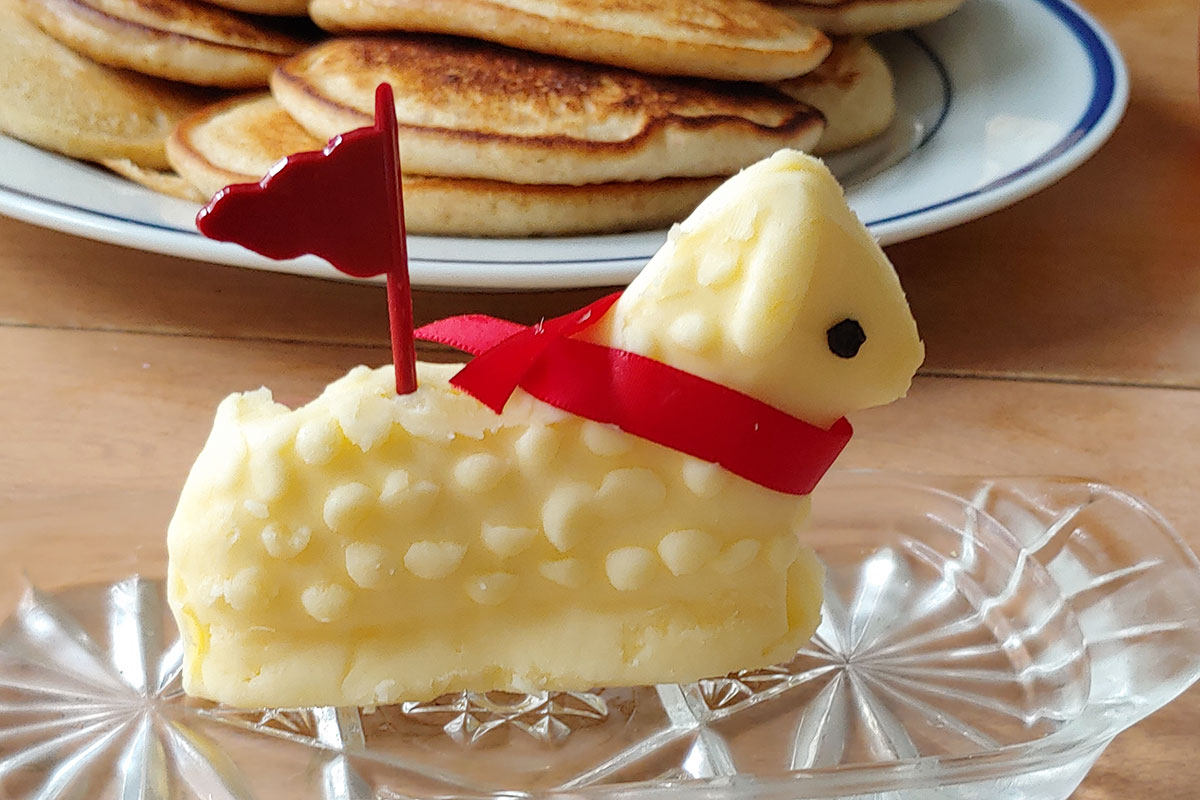

Our dinner table is adorned with the sort of Easter decor familiar to many Americans, with rabbit placemats and painted rabbit or egg figurines, plus two white candles in tall glass pillars that symbolize Jesus’s resurrection and God’s presence at our table. And at the center, in all its golden glory, is the butter to be slathered on our slices of bread, sculpted into a lamb. There it watches us with its beady eyes, year after year, as we fill our plates with ham, bread, and a variety of spring vegetables, and as we sit down to say grace before digging in.

The Butter Lamb: A Family Affair

A butter lamb has taken center stage on my family’s Easter table for as long as I can remember. It is exactly as it sounds: a wad of butter shaped into a curly-coated lamb with peppercorn eyes. Around its neck is a red ribbon, representing the blood of Christ. Stuck in its back is a red plastic “alleluia” flag, a symbol for peace on Earth and victory over death. In our family, I have always known it to look this way. My sister and I would battle over who got to behead it as kids, though we learned to cut at the end instead, out of respect for Jesus.

Our lamb is Malczewski’s four-ounce version found in supermarkets like Tops or Wegmans, though the brand also sells two-, six-, and ten-ounce versions, plus the whopping pound-and-a-half version. All sizes can be found downtown at Buffalo’s Broadway Market.

Although the famous Butter Lamb stand at the Broadway Market wasn’t established until 1963, the market’s long history explains the origin of the Buffalo tradition. Polish and Eastern European immigrants migrated to the Great Lakes region during the late 1800s. By the 1870s, they settled into communities in Rust Belt cities like Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Buffalo. They formed neighborhoods which soon became known as Kaisertown and Polonia in Buffalo’s East Side. In need of a local place to buy fresh meat and produce, Polish families established the Broadway Market in 1888, providing a place of food, community, and the continuing traditions of home.

Over the decades, the Broadway Market survived fire and remodeling. Old Polish traditions, too, survived and were revived in downtown Buffalo. In the 1960s, Dorothy Malczewski, owner of Malczewski’s Chicken Shoppe (also located in the Broadway neighborhood), was preparing for Easter. In her attic, she found a small, lamb-shaped mold, brought to the United States by her immigrant father. After learning its origin, she planned the perfect way to connect her Polish Catholic heritage to the wider Buffalo community, by debuting the baranek wielkanocny: the Easter butter lamb.

“She introduced them at her corner store on the East Side to try them out, and they were a hit!” says Dorothy’s grandson, Jim Malczewski. “When she opened the poultry stand in the Broadway Market, she began selling them there too.”

Since the opening of Dorothy’s stand, Buffalonian families have adopted the butter lamb tradition, regardless of Polish or Catholic background, making it a regional staple.

The butter lamb was always a family affair. Jim recalls the values instilled into him as he worked alongside his grandmother at the market as a teen: “She was a family-first person. She respected the Polish and Catholic traditions. Every Christmas and Easter, she’d gather the family and host right in her basement.” During the Easter season, “she’d run the stand beginning at 4 a.m. and not get home until after 7. I started working that stand when I was twelve or so, for about six years, and there’s nothing quite like learning how to work by spending twelve to fourteen hours with your grandma.”

Dorothy’s son and Jim’s father, also Jim, recalls those first years making butter lambs right in their home. When he was twelve, he helped tie the ribbons and make the flags. It was the Malczewski way, to make every single one of the lambs by hand, with the whole family—brothers, wives, and children all involved.

While the family no longer runs Malczewski’s, their legacy continues thanks to Camellia Meats, a local, fourth-generation Polish American business. After the elder Jim retired in 2012, he sold the business to the Cichockis, the Polish American family that founded Camellia Meats in 1935. The younger Jim explains, “No one in the family could take over the stand. I had my own business, and my father and brothers were retired and lived out of state. Adam Cichocki from Camellia Meats really expressed an interest—and even more, wanted to keep everything the same.”

Adam Cichocki, great grandson of Camellia Meats’ founder Edmund Cichoki Sr., now oversees the production of Malczewski’s Butter Lambs during the Lenten season. “As a kid, [the butter lamb] was always a fun tradition for Easter, and as I got older, I realized how big of a tradition it was,” he says.

Over the years, the production of butter lambs has expanded dramatically in Buffalo. Annually, Malczewski’s sells around 100,000 lambs, using over ten tons of butter. To keep up with the demand provided by local supermarkets that have extended their businesses down the East Coast, Cichocki explains that some elements of the production process became automated. They now use machines to mold the lamb figurines from fifty-five-pound blocks of butter, but the product has remained the same.

“What really matters is the family name and continuing the tradition,” the younger Jim says.

A Lenten Lamb’s Origins

“Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.”

To better understand the symbolism of John 1:29, I talked with Mary Lou Wyrobek, a religious educator and active member of several Polish American organizations in Buffalo, including the Permanent Chair of Polish Culture, Polish Arts Club, and the Chopin Singing Society.

As she explained, in the Book of Exodus, God commands the Israelites in Egypt to sacrifice an unblemished male lamb and mark their doorposts with its blood. This act spares them from God’s destruction as he passes through Egypt, taking the lives of every firstborn and spreading plagues to all those in unmarked homes. Thus, the lamb becomes known as the Paschal Lamb, or Passover Lamb.

In the Christian Gospels, the ritual of Passover and the Lamb are developed as symbols for Jesus. In John’s Gospel, Wyrobek explains, Jesus is presented as the unblemished lamb, free from sin. While the four gospel narratives differ on the timeline of Jesus’s last days, his death occurs close to the time of Passover, strengthening the association between Jesus and the symbolic sacrifice of Passover.

Sophie Knab, a Polish American author and blogger, placed the butter lamb in the context of the austere season of Lent in the Christian liturgical calendar. She explained how Catholics refrained from eating meat and dairy during Lent. In Poland, “they lived on veggies, potatoes, and vegetable oils, often from sunflowers or hemp seeds. Eggs were rarely eaten during the Lenten season, which is why there’s such significance with egg decorating traditions there.”

The end of Lent, celebrated by Easter, was an opportunity for people to go all out by eating bread, fat, and meats, and shaping butter and sweets into lambs. According to Knab’s research, the tradition goes back at least to the seventeenth century.

Easter Sunday not only welcomes the resurrection of Christ but also the arrival of spring, celebrated with feasts of bread, cake, pork, and dairy. Traditionally, Polish Easter baskets are blessed the day before on Holy Saturday and filled with Polish sausage, greenery like boxwood and pussy willows, and butter.

Father Czeslaw Krysa, rector of St. Casimir Roman Catholic Church in Kaisertown, Buffalo, tells me that in the Polish tradition, the lamb is placed centrally on the Easter table, often atop some greenery and accompanied by the red banner. The Polish lamb is typically made of sugar or bread, though the butter lamb can be found regionally in southern Poland.

The lamb we see today in Buffalo is nearly identical to this tradition, though the greenery is new to me. Sophie Knab explains its significance as a combination of Pagan and Christian beliefs. Greenery represents a renewal of life, associated both with the coming of Spring and the resurrection of Christ. “It’s a combination of centuries of faith and a historically agrarian society.”

One change that Dorothy Malczewski introduced was the addition of purple flags in the butter lambs’ backs. According to Father Krysa, it was a way to include local Evangelical pastors who too wanted to take part in this tradition and have a symbol of Christ on their Easter table. “It’s a connecting thing for the community,” he said. “It represents something so much bigger than us, and has become a symbol of Buffalo. It’s unique, with an ultimate meaning from faith passed down over hundreds of years.”

These Traditions That Still Remain

A sense of pride is at the core of the butter lamb’s unusual tradition. It is not only a symbol of the Lamb of God or the coming of spring but represents the persistence of Polish Catholic traditions which shape our holiday rituals in Buffalo.

Buffalo is a “varied city,” as Wyrobek puts it, where people come from many different walks of life. But there is no doubt of the Polish influence on this city, as we celebrate the Dyngus Day parade and make our annual pilgrimage to the Broadway Market for kielbasa, pierogies, and a certain butter lamb.

It is the tradition’s persistence which imbues such a sense of pride. The butter lamb is “one of those silly goofy things, like a pet rock, but everyone knows what it is. It’s about seeing that smile… I still get texts from friends when the lamb hits the stores,” Jim Malczewski says.

For Jim’s father, the butter lamb is an opportunity to reflect on his family’s legacy: “The recognition was phenomenal. My mother just loved it. Easter was a special time of year.” For the Malczewskis, Easter Sunday was finally a day of rest. It was a day of family and a day of celebration, not only for the coming of spring or Christ but for the successful closing of the butter lamb season.

Adam Cichocki and Camellia Meats now carry the torch of continuing the tradition, and while it is no easy feat, the impact it has on the community makes it all worthwhile.

For Knab, the opportunity to “spread” her culture and share the practices from her family’s home carries the most meaning. As her books and blogs focus on her Polish history and heritage, sharing her cultural traditions lends her more than just a sense of pride: it is her life’s work, an opportunity to connect with others and to the past.

In collaboration with St. Casimir’s Polish Easter Video Project, Knab has taken the opportunity to educate and cultivate community one step further. Partnering with Father Krysa, she demonstrates how to make a butter lamb. If you want to adorn your table this Easter with a symbol of Christ, or seek another way to welcome in spring, all you’ll need is a softened stick of butter, a few toothpicks, and some crafts supplies you can probably find at home.

Traditions like these not only connect us to our families and heritage but bind together entire communities in cultural practice and legacy. They allow us to pass cultural knowledge from one generation to the next, continuously shaping our ways of life. We may not know the exact origin of traditions like the butter lamb or deeply understand their significance. As Wyrobek says, “The reasons have gone by the wayside, but these traditions still remain.”

This spring, in the spirit of persisting tradition, I find myself back home in Buffalo after several months away, celebrating Easter and the coming of good weather. In preparation for my family’s usual feast at my grandmother’s, I make my way downtown, alongside my father, to the Broadway Market. As we take the escalator down from the parking garage, I am overcome with nostalgia, the scent of freshly popped kettle corn hitting my nose, a bustling market stand with bright flowers right in my line of sight. On the market floor, we mosey from stand to stand, beholding this year’s bounty of painted eggs, baked goods, and local handmade jewelry.

We’ve joined thousands of other Buffalonians in this annual pilgrimage, admiring decades worth of community work and memory-making, and this year, we search for one thing in particular: a butter lamb from Malczewski’s Easter Stand.

Tiffany Stayer is a writing intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, a former educational programs intern at the National Museum of American History, and an alum of Daemen University in Buffalo, where she studied history and psychology.