Stories from

the American Ginseng Community

Welcome to American Ginseng: Local Knowledge, Global Roots. This exhibition presents the stories of a wide variety of people with intimate knowledge of the harvest, cultivation, trade, medicinal use, and conservation of this fascinating plant. You can also add your own ginseng story.

American ginseng, as you will learn from its practitioners and advocates, is highly prized in Asian traditional medicine, and is the most valuable botanical plant that grows in the forests of the Eastern United States and on Midwestern farms.

Due to its high value and the degradation of its natural habitat, wild American ginseng faces many threats, from encroaching suburban sprawl and extraction industries to the environmental impact of climate change. Conservation efforts—protection by government agencies, education on good stewardship, cultivation in forest settings, and research into accelerating its propagation—help ensure the survival of American ginseng for future generations.

Through presenting our research about the personal experiences of the people who interact with American ginseng, we hope to stimulate greater respect for the plant. By sharing traditional knowledge about the many wonders of American ginseng, we seek to increase education and conservation efforts for the “green gold” of the plant world.

Historic Roots of the American Ginseng Story

In 1784, the clipper ship Empress of China set sail for Canton (Guangzhou) loaded with more than thirty tons of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius). Thus began the trade of this valuable medicinal plant, which grows wild in the deciduous forests of the Appalachian Mountains, linking two nations half a world apart.

The year 1784 marks a milestone, but the history of American ginseng and its ties to Asia run much deeper. According to plant genetic research, ginseng probably traveled across the Bering Strait from Asia in prehistoric times, taking root in the habitat that most closely resembled its mountainous home.

Native Americans in eastern North America knew and used the plant. Two Jesuit missionaries, one in Québec and one in China, made the connection between the North American and Asian varieties of ginseng in the eighteenth century. This connection helped foster trade between the two countries, and consequently fur trappers and traders in what became Canada and the United States knew the value of ginseng to the Chinese market even before the American Revolution. The plant may have helped finance the Revolution and certainly bolstered the fortunes of early explorers and settlers, including Daniel Boone.

From the early days of settlement of the Appalachian region, gathering and selling wild ginseng helped families make ends meet or afford a “little extra,” such as new school shoes or holiday presents. Deliberate ginseng cultivation began around the turn of the nineteenth century and has since expanded to a multimillion-dollar industry. Marathon County, Wisconsin, is the center of large-scale ginseng cultivation, on farms owned and run by several generations of family members. Also thriving, especially in Appalachia, is the “forest farming” of ginseng, which simulates wild conditions.

We hope you enjoy exploring ginseng’s story, featured here through a selection of historical and contemporary perspectives of the people who work alongside it.

-

Joshua AlbrittonBioscience TechnicianGreat Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee/North Carolina

-

WenYi Bai & Hyon S. MoonOwner and Manager, Danji RestaurantCentreville, Virginia

-

Robin BlackGinseng Coordinator, West VirginiaCharleston, West Virginia

-

Teresa BoardwineHerbalist and Owner, Green Comfort School of Herbal MedicineCastleton, Virginia

-

Emma Lucy BraunBotanist and EcologistCincinnati, Ohio

-

Barbara Breshock and Amy CimarolliForesters, Leaders of WV Women Owning WoodlandsWest Virginia

-

Eric BurkhartAppalachian EthnobotanistCentre County, Pennsylvania

-

Edward BurlettSouthwest Regional Supervisor, Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer ServicesWytheville, Virginia

-

Chip CarrollSteward, United Plant Savers SanctuaryOhio

-

Wendy CassBotanistShenandoah National Park, Virginia

-

Carole & Ed DanielsGingeng Growers and Owners, Shady Grove BotanicalsRandolph County, West Virginia

-

Ruby DanielsConsultant Herbalist and Forest FarmerStanaford, West Virginia

-

Fran DayDirector of Institutional Advancement, Arrowmont School of Arts and CraftsGatlinburg, Tennessee

-

Robert EidusGinseng FarmerMarshall, North Carolina

-

Victoria Persinger FergusonMember, Monacan Indian Nation Historic Resource Committee; Program Coordinator, Historic Fraction Family HouseRoanoke, Virginia

-

Chris FirestoneGinseng Coordinator, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation & Natural ResourcesHarrisburg, Pennsylvania

-

Iris GaoGinseng Researcher and Plant Molecular BiologistMurfreesboro, Tennessee

-

Randy HalsteadGinseng DealerPeytona, West Virginia

-

Jim HamiltonCounty Extension Director, Watauga CountyBoone, North Carolina

-

Larry HardingGinseng GrowerFriendsville, Maryland

-

Tony HayesGinseng Dealer, Ridge Runner Trading CompanyBoone, North Carolina

-

Janet Hamric HodgeGinseng Buyer and Wildlife Resources CommissionerSmithville, West Virginia

-

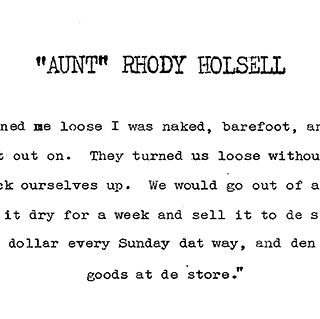

Rhody Holsell & George ThompsonEnslaved Peoples and Ginseng SellersVarious locations

-

Paul HsuGinseng GrowerMarathon, Wisconsin

-

Sara JacksonGinseng ConservatorBat Cave, North Carolina

-

Pierre Jartoux & Joseph-François LafitauEarly Figures in Ginseng KnowledgeFrance, Canada, and China

-

Carol JudyHerbalist, Root Digger, and Forest GrannyJellico, Tennessee

-

Mary LawsonGinseng DealerAbingdon, Virginia

-

Danny LeeChef and Restaurateur, Mandu, Anju, and ChikoWashington, D.C.; Arlington, Virginia; Bethesda, Maryland; and Encinitas, California

-

Tina LeeGinseng GrowerWausau, Wisconsin

-

Yesoon LeeChef, ManduWashington, D.C.

-

Susan LeopoldEthnobotanist and Executive Director, United Plant SaversParis, Virginia

-

Anna LucioMarketing Specialist, Kentucky Department of AgricultureFrankfort, Kentucky

-

Doug ManningBiologist and ConservatorNew River Gorge National Park and Preserve, West Virginia

-

James McGrawProfessor Emeritus, Plant Population Biology and EcologyMorgantown, West Virginia

-

Joe PigmonGinseng Harvester and StewardEastern Kentucky

-

Anna Plattner & Justin WexlerManagers, American Ginseng PharmTreadwell, New York

-

Randi PokladnikGinseng Poaching ResearcherWest Virginia

-

Laurie QuesinberryGinseng Harvester and ConservatorMeadows of Dan, Virginia

-

Tae RimDoctor, Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine ClinicAnnandale, Virginia

-

Karam ShebanGinseng Conservator and ResearcherNew Haven, Connecticut

-

Cliff & RandyGrowersNorthwestern Pennsylvania

-

George Stanton & A.R. HardingEarly Figures in Ginseng KnowledgeNew York and Ohio

-

Paul Strauss & Tanner FilyawGinseng Growers and Forest StewardsRutland, Ohio

-

Caleb TrivettGinseng Harvester, Grower, and DealerRoan Mountain, Tennessee

-

Steve TurchakGinseng StewardJohnstown, Pennsylvania

-

Jun WenResearch BotanistWashington, D.C.

-

Anna LucioMarketing Specialist, Kentucky Department of Agriculture

Anna Lucio has worked directly with Kentucky’s ginseng program for thirteen seasons. She continues to learn as much as she can about the history, culture, and conservation of ginseng—to benefit both the plant and the dealers who she must ensure follow regulations.“We’re not just regulating this because we want to regulate it. We are regulating it ... to help the dealer communicate to the harvesters, so if our ginseng looks better at the time of certification and export, it all starts the first time it is harvested.”

Anna Lucio has worked directly with Kentucky’s ginseng program for thirteen seasons. She continues to learn as much as she can about the history, culture, and conservation of ginseng—to benefit both the plant and the dealers who she must ensure follow regulations.“We’re not just regulating this because we want to regulate it. We are regulating it ... to help the dealer communicate to the harvesters, so if our ginseng looks better at the time of certification and export, it all starts the first time it is harvested.”When Anna Lucio started her work with ginseng duties in the Office of Agricultural Marketing at the Kentucky Department of Agriculture, she was afraid that she didn’t possess “ginseng eyes”—the ability to spot the elusive forest botanical among other plants in its natural habitat. Even though she is Kentucky born and bred and was raised on a farm, she didn’t have much experience with the plant. But she needn’t have worried.

A friend took her to her family’s forested property, where they had been nurturing the wild ginseng plants. When she parked at the edge of the woods no less than “two car lengths away,” she reports, “I looked up in the woods and I saw twenty to thirty plants sitting there. We spent about four or five hours in the woods in a different spot and came out with fifteen roots. And her dad said, ‘I would go “sengin” with that girl anytime. You tell her to come home anytime she wants to go.’”

Anna Lucio, seated at her desk in the Office of Agricultural Marketing at the Kentucky Department of Agriculture, shows off her pipe-cleaner model of a ginseng plant. This “specimen” is part of a large collection of educational materials and collected fascinations that line her shelves. Photo by Betty Belanus, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives American ginseng has become a bit of an obsession for Lucio, as well as the basis of her job. Her Frankfort office is a one-room museum of, and classroom on, ginseng. Exemplary specimens, as well as items that tell cautionary tales (harvesting underage ginseng or damaging roots when drying) line the walls and shelves. Behind her desk is a large plastic box containing instructional display materials she brings to the Kentucky State Fair and other venues to help educate the public about the plant’s growing cycle, regulations governing its harvest, and proper root digging methods.

Lucio enjoys the stories that she collects during the state fair, where she gets many positive reactions to her display. “We get a lot of response from people saying, ‘Oh my goodness! I remember my granddad harvesting that.’ Or even ‘my grandma did it!’” As a woman in this largely male-dominated world of ginseng harvesting and dealing, Lucio is particularly interested in learning more about women and ginseng. “Women were the medicine collectors, it seems like, in our eastern Kentucky communities.”

Anna Lucio holds an old pickaxe, such as those used by some ginseng harvesters. Lucio has several examples of ginseng digging tools hanging in her office to illustrate “the best and the worst.” Photo by Betty Belanus, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives Her job is complex, and a flurry of activity descends upon her during the fall season. Lucio interacts mostly with ginseng dealers, who need to maintain a protocol for gathering and reporting information if they want to keep their required licenses in order. “We need to do better as an industry of tracking this and how we’re handling it.” Lucio offers guidance to the dealers for legally selling and utilizing this resource and puts the responsibility directly on them to build and maintain a future for the plant. “They tell me their grandfather used to do this; that’s fantastic and I love that heritage.”

Lucio takes pride in conserving fresh ginseng roots that are very small and not valuable to the dealer, typically five to ten years old. She helped Kentucky ginseng dealers create a legal fresh (as opposed to dried) ginseng market around 2007 and has seen many more fresh roots since then. She recalls one “marriage” she made between a dealer with small fresh, legal roots and a grower of wild-simulated ginseng looking for legal rootlets. In another instance, a licensed dealer contacted her for ideas of what to do with such roots—legal for commerce, but not large enough to make much profit. Based on their conversations, the dealer planted 100 of those roots in a bed in 2014; seven years later, the patch now has a few thousand plants. In short, Lucio likes to “think outside the box” and to connect the strong history of American ginseng in Kentucky to its future: “We’ve got to see where we’ve been to know where we need to go.”

-

Anna Plattner and Justin WexlerManagers of American Ginseng Pharm

Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler manage the field operations of American Ginseng Pharm (AGP), a large-scale agroforestry farm in upstate New York. AGP uses innovative methods to cultivate American ginseng in a way that benefits both humans and the Earth.“We want to encourage landowners to grow ginseng themselves, to conserve the biodiversity of the forests they own while making a profit.” —Anna Plattner

Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler manage the field operations of American Ginseng Pharm (AGP), a large-scale agroforestry farm in upstate New York. AGP uses innovative methods to cultivate American ginseng in a way that benefits both humans and the Earth.“We want to encourage landowners to grow ginseng themselves, to conserve the biodiversity of the forests they own while making a profit.” —Anna PlattnerBoth Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler grew up immersed in the natural beauty of the Catskill Mountains and nearby Hudson Valley. Plattner studied natural resources at Cornell University, where she first encountered the concept of “conservation through cultivation,” which promotes forest farming and its positive impact on ecosystems. Wexler studied ethnoecology and education at Marlboro College and Bard College. The two met at a master naturalist training program and immediately clicked.

Today, the husband-and-wife team run the world’s largest wild-simulated ginseng operation: American Ginseng Pharm. AGP started more than a decade ago when Eva Tsai, a charismatic businesswoman with a passion for herbal medicine, reached out to internationally recognized ginseng expert Bob Beyfuss. Not long after AGP planted the first seeds near Plattner’s hometown, she joined the operation and became its general manager within two years. Wexler jokes that he was “roped into” joining the effort, although Plattner says that he was indispensable for their early establishment—and continues to be—as the native plant and geographic information specialist.

Anna Plattner, manager of American Ginseng Pharm, poses with a mature American ginseng plant growing on company land. Photo courtesy of Anna Plattner Together, the couple enthusiastically applies cutting-edge agroforestry techniques to efficiently grow wild simulated ginseng. Their methods derive from historical stewardship practices, which create the ideal environment for the plants to thrive without the use of heavy machinery or soil amendments but decrease the high labor time and expenses associated with such techniques.

As Plattner explains, “Our way of growing ginseng mimics natural disturbances, which is highly beneficial for healthy forest systems. We find that within a few years of planting a site with ginseng, many native medicinal plants—such as blue cohosh, maidenhair fern, and wild ginger—increase in population.” In this way, they help the entire forest ecosystem while taking harvest pressure off existing wild ginseng populations.

Anna Plattner and Justin Wexler carefully survey and tend the land, leased by the American Ginseng Pharm, in order to mimic the natural ecosystem that ginseng prefers, while still ensuring its success as a crop. Photo by Morgan Thapa Moreover, AGP leases much of its planting land, providing landowners with a source of income and an alternative to destructive logging practices. As Wexler explains, “Logging operations in the Catskills decimate local ecosystems, taking out keystone trees, bringing in invasive species, and ultimately destroying biodiversity. We try to provide an alternative way to profit from woodland, which allows for the maturation of old-growth forest ecosystems.”

Plattner and Wexler also maintain a small forest farm of their own and host workshops and local natural-history walks sponsored by their organization, Wild Hudson Valley. Their property is a United Plant Savers-certified botanical sanctuary, perfect for hosting classes and overnight camping.

The COVID-19 crisis has increased the global demand for herbal medicine, and climate change has increased the need for regenerative agricultural practices. Plattner and Wexler feel that wild simulated ginseng cultivation is key in the journey to a healthier humanity and planet overall.

Contributor: Morgan Thapa -

Barbara Breshock and Amy CimarolliForesters, Leaders of WV Women Owning Woodlands

Co-founders of the West Virginia chapter of Women Owning Woodlands, Barbara Breshock and Amy Cimarolli are career foresters blazing a trail for women in the traditionally male-dominated world of forest management. Breshock, Cimarolli, and other women in the organization steward woodlands to enhance habitats for forest botanicals, including ginseng.“My forest is steep and rocky. I couldn’t put a [deer exclosure] fence in up there, but I fenced this place to get a stand of ginseng going. They’re going to be my mother plants to produce seed. And I’ll take that seed up into the forest.” —Amy Cimarolli

Co-founders of the West Virginia chapter of Women Owning Woodlands, Barbara Breshock and Amy Cimarolli are career foresters blazing a trail for women in the traditionally male-dominated world of forest management. Breshock, Cimarolli, and other women in the organization steward woodlands to enhance habitats for forest botanicals, including ginseng.“My forest is steep and rocky. I couldn’t put a [deer exclosure] fence in up there, but I fenced this place to get a stand of ginseng going. They’re going to be my mother plants to produce seed. And I’ll take that seed up into the forest.” —Amy CimarolliIn many Central Appalachian communities, the propagation, tending, and harvesting of understory forest species has traditionally been the job of women. Members of Women Owning Woodlands (WOW), historically barred from decision-making about woodlands by laws that prohibited women from owning property, acquire the skills needed to manage forests together. Many women drawn to West Virginia WOW are particularly interested in the sustainability of non-timber forest products.

While managing their own woodlands in Tucker and Raleigh counties, Breshock and Cimarolli continually emphasize the restoration and enhancement of habitats for forest botanicals, including cohosh, goldenseal, bloodroot, mayapple, wild orchids, and, of course, ginseng. Cimarolli started her ginseng patches from seeds supplied by the Yew Mountain Center in Pocahontas County. Focused on the reclamation of wild ginseng patches, her forest restoration plan prioritizes the removal of invasive species by first clearing the places where ginseng would thrive.

First-year ginseng, also known in the coal fields as a “biddy’s foot.” Photo by Mary Hufford Stewarding ginseng patches not only involves beating back invasives but protecting ginseng from the deer population. Using the “brushing” technique, Cimarolli covers ginseng patches with a latticework of fallen branches to discourage deer from grazing.

“You can see the logs,” she said, pointing to the northeast facing slope above her. “The tangle of big hemlock logs—that’s where I crawled into to put my ginseng.”

Cimarolli has life cycles in mind, including her own. “This is definitely a long-term project. I have the energy now to do it, so it’s a good time to make investments, so maybe when I’m elderly I can still get up here and harvest some goldenseal for my sore throat, or some ginseng for my tea.”

Amy Cimarolli finds two “ginseng babies.” Photo by Mary Hufford Breshock, now retired from decades working as a state forester with the West Virginia Division of Forestry, plants ginseng, ramps, and goldenseal on Three Springs Farm, her woodlands in Raleigh County. Her strategy for enhancing ginseng habitat: deer hunting. It’s a skill she learned in a program offered by the Division of Forestry: Becoming an Outdoor Woman.

“I felt guilty as a forester, that deer were doing so much damage to the forest, and I wasn’t doing anything to help!” she explained.

Contributor: Mary Hufford -

Caleb TrivettGinseng Harvester, Grower, and Dealer

Caleb Trivett has enjoyed the forested mountains of East Tennessee since he was a boy. Ginseng always figured largely in his love of the woods and its many understory plants. He hopes to grow a legacy and to learn ever more about ginseng on his North Wind Farm.“Seeing something in its pure form and happy—and being able to share that with someone—is the reason I come to mountains to dig ginseng.”

Caleb Trivett has enjoyed the forested mountains of East Tennessee since he was a boy. Ginseng always figured largely in his love of the woods and its many understory plants. He hopes to grow a legacy and to learn ever more about ginseng on his North Wind Farm.“Seeing something in its pure form and happy—and being able to share that with someone—is the reason I come to mountains to dig ginseng.”Caleb Trivett made headlines in East Tennessee when he was in seventh grade. “Youth Walks Out Unharmed,” read the local newspapers. He had set off on a solitary overnight trip to camp in the woods but neglected to make his intentions known to his family, causing more than 300 people to search for him. Having enjoyed hunting ginseng and deer in the heavily forested mountains with his grandfather and father since a young age, he didn’t see the harm at the time.

Trivett has learned the best methods of planting forest botanicals by trial and error. He believes high elevations grow tougher plants, especially ginseng, and that those stronger genes will help him build a sustainable organic population near his home. Photo by Arlene Reiniger, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives Trivett still enjoys being alone in the woods. But he now has a higher purpose: to ensure that wild and wild-simulated ginseng have a future in his beloved mountains. Indeed, those mountains called him back home when he was twenty-one, after just a few years in college. Learning more from studying the plants and their environment first-hand, he started planting and nurturing ginseng—including on other people’s land for a portion of the profits.

Caleb Trivett tends to some beds of ginseng, picking wild berries and noting where deer have foraged along the way. Photos by Arlene Reiniger, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives In 2020, Trivett purchased his own plot at a high elevation, which he calls North Wind Farm. His belief is that “any ginseng up high, probably has got some really strong genes.” He supplements the wild ginseng already growing on the land by planting seeds that may help realize his dreams of establishing a strong local strain of organic ginseng in the future.

Caleb Trivett discusses concerns over the preservation of wild ginseng | Read audio transcriptTrivett believes strongly in the health properties of ginseng and wants to promote its domestic use. He uses all parts of the plant himself, even adding the green leaves like lettuce to sandwiches. Knowing that many Americans do not enjoy ginseng’s often-bitter taste, Trivett tries blending ginseng with other, more familiar herbs like mint. He also tries cinnamon, lemon, and honey to help create a more pleasing taste and to expand ginseng’s use.

All in all, Trivett shows a deep respect for ginseng and its enduring existence in the East Tennessee mountains. “You look at a plant and marvel how it may be older than you. If Trivett has anything to do with it, ginseng will continue to thrive and to sustain the health and the economy of the area for years to come.

“Ginseng Song” | Video by Albert Tong

-

Carol JudyHerbalist, Root Digger, and Forest Granny

Born in Florida and raised in Georgia, Carol Judy (1949–2017) made her way to her grandfather’s home state of Tennessee at age nineteen, settling in Eagan, in the Clear Fork Valley. She co-founded, with Marie Cirillo and others, the Clearfork Community Institute, learning from fellow woods walkers to identify and harvest roots and herbs of the forest.“I knew that local young people were really being denied chances, and I knew I couldn’t do much about it by myself. But the ones that would follow me into an institution that I was helping to develop, they were the ones I would work with. And I met them digging in the woods.”

Born in Florida and raised in Georgia, Carol Judy (1949–2017) made her way to her grandfather’s home state of Tennessee at age nineteen, settling in Eagan, in the Clear Fork Valley. She co-founded, with Marie Cirillo and others, the Clearfork Community Institute, learning from fellow woods walkers to identify and harvest roots and herbs of the forest.“I knew that local young people were really being denied chances, and I knew I couldn’t do much about it by myself. But the ones that would follow me into an institution that I was helping to develop, they were the ones I would work with. And I met them digging in the woods.”In many places in the Appalachian Mountains, the wise female elder who people turned to for advice, healing, and midwifery skills was known as a granny woman. Carol Judy exceeded that role, becoming the kind of leader most urgently needed in these times. Judy elevated her influence “from the holler to the hood,” from the local to the global, to tackle issues of race, gender, and environmental injustice in Appalachia and around the world. With Michele Mockbee and Ricki Draper, Judy founded Fair Trade Appalachia. She was affectionately known to many as “Forest Granny.”

“Carol ginsenged everywhere, and she taught everyone,” recalled April Jarocki, who runs the Cyber Café at the Clearfork Community Institute. “In July of 2014, I was hit head on and totaled my car and dislocated my left elbow, so I had no job, no car, no income, and Carol was like: ‘You can ginseng, you can yellow root, you can sell this stuff, you can make things.’ And she took me out and showed me what ginseng was and how to find it. I found my very first ginseng root in that little patch of woods right there.”

As Judy saw it, the region’s persistent poverty and environmental degradation are legacies of more than a century of resource extraction and the related displacement of hundreds of thousands of Central Appalachian people. With out-migration in the mid-twentieth century, she described, the region hemorrhaged local knowledge and collective memory that had traditionally ensured community-based stewardship practices.

“She believed that understanding ‘old man seng’ was a way of understanding and interpreting the entire forest as a system seven generations forward and seven generations back,” wrote Michelle Mockbee.

Carol Judy with three-prong ginseng root and top, 2009. Photo by Michelle Mockbee Gabby Gillespie, a community organizer in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, recalled Judy’s rule of thumb for harvesting ginseng: “She always taught me: make sure you see, in a small area, at least seven other plants before you harvest one.”

Judy attended United Nations meetings in New York, represented grassroots rural women at a conference in Istanbul, and co-hosted an exchange among Guatemalan and Appalachian activists at the Clearfork Community Institute. She appeared at festivals, conferences, and demonstrations throughout the Appalachian region, leading workshops and speaking out about the need to build an alternative economy. She advocated a way of life centered around the stewardship of the region’s biological and cultural diversity.

Carol Judy talks with students about ginseng and goldenseal at Roanoke College, during a 2016 workshop series presented with the Beehive Collective. Photo by Mackay Pierce Judy was famous for her woods walks and her thousand-megawatt smile. She drove a yellow truck, had blue and purple hair, smoked “knik knik” (Uva ursi aka “bearberry”), laughed her infectious laugh, and called the earth her lover.

But her environmentalism did not stop at the earth.

“Frankly,” as she told Felix Bivens, “It is about saving humanity, not just the mountains.”

Carol Judy walks Amelia Taylor’s woods. Photo by Amelia Taylor Contributor: Mary Hufford -

Carole and Ed DanielsGinseng Growers and Owners, Shady Grove Botanicals

Carole and Ed Daniels are forest farmers and crafters who use ginseng and other healing botanicals. A former wild ginseng harvester, Ed is now an avid and vocal steward of the plant. Carole is a partner in the farming, production, and promotion for their company, Shady Grove Botanicals.“There’s more to it than just digging a hole and throwing a root in it. There’s a connection.” —Ed Daniels

Carole and Ed Daniels are forest farmers and crafters who use ginseng and other healing botanicals. A former wild ginseng harvester, Ed is now an avid and vocal steward of the plant. Carole is a partner in the farming, production, and promotion for their company, Shady Grove Botanicals.“There’s more to it than just digging a hole and throwing a root in it. There’s a connection.” —Ed DanielsWhen Ed Daniels was a teenager, he dug wild ginseng from the West Virginia mountains for money. “If I wanted new school clothes, I dug ginseng and sold it. I bought my first car, a VW bug, with ginseng.” Although he had learned about ginseng from older relatives, “no one taught me [to be a good steward]. Now I go back to some of those areas and ... the ginseng is dug out.”

In the early 2000s, Ed and Carole began growing ginseng as forest farmers. In 2016, they began Shady Grove Botanicals after expanding their farming to more forest botanicals, such as elderberry, goldenseal, and blue and black cohosh. Carole aids Ed in planting, tending, and harvesting, and she also takes charge of promoting the business via social media.

Ed is quick to admit ginseng is his favorite plant. He checks on the progress of the plants almost daily during growing season and “stops just short of naming them all.” His great-grandfather worked at a logging camp and took charge of “patching up” ailing workers; remedies included his recipe for ginseng leaf tea with teaberry and honey, plus the optional ingredient of local alcohol, which Ed and Carole still make. They’ve developed new tea blends, as well as tinctures, salves, and herb-infused honey.

Video by Albert Tong

The Daniels are passionate about using their forest-farming experience to educate people about the importance of stewarding important native botanicals, especially ginseng. Their young grandson, Briar, has his own “patch” of plants, and even as a toddler could already identify ginseng.

This passion led to pairing Ed with budding forest farmer Clara Haizlett from Bethany, West Virginia, as an apprentice through the West Virginia Folklife Program in 2020. Even though the pandemic made face-to-face meeting difficult, they found socially distanced ways of sharing information. For instance, Ed and Carole created a “scavenger hunt” for Haizlett to use on her own land to learn how to identify beneficial native, as well as harmful invasive, plants.

About the Daniels, Haizlett observes, “They have plenty of experience, but they also have innovation. Just in the past year they are acquiring different plants and trying different practices. I wanted to work with someone who is familiar with the traditional practice but is also innovating the new features of ginseng and botanicals.”

Their current approach to forest farming, and their devotion to education, more than makes up for Ed’s past ginseng digging transgressions. “We put back more ‘sang’ than I’ll ever dig in my life. We know the power of this plant.”

-

Chip CarrollGinseng Conservator, Educator, and Monitor

Chip Carroll became a ginseng steward after studying biology in college. He and his family live near the United Plant Savers Sanctuary, where he presents educational programs and maintains the grounds, including overseeing the ginseng. He plants, digs, and has dealt ginseng, and has officially monitored ginseng populations in Ohio state forests since 2006.“Ginseng really ties together the economy, the social, and the environmental for people… and that’s a great tool that gets people interested and engaged and involved in their forests.”

Chip Carroll became a ginseng steward after studying biology in college. He and his family live near the United Plant Savers Sanctuary, where he presents educational programs and maintains the grounds, including overseeing the ginseng. He plants, digs, and has dealt ginseng, and has officially monitored ginseng populations in Ohio state forests since 2006.“Ginseng really ties together the economy, the social, and the environmental for people… and that’s a great tool that gets people interested and engaged and involved in their forests.”Chip Carroll drives a white SUV with a license plate that reads “GINSENG.” That’s one indication of how much the plant is, as he puts it, “in his blood.” He also has an impressive ginseng-themed tattoo running the length of his left calf. Before taking a class in field biology at Hocking College in Nelsonville, Ohio, though, Carroll did not know that ginseng grew in his home state, or how important it would become to him.

Growing up in northeastern Ohio around Youngstown, Carroll developed an interest in outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing, and gathering wild mushrooms. He interned with United Plant Savers as an undergraduate and joined AmeriCorps after college. AmeriCorps assigned him to work with Rural Action in Athens, Ohio, in its Sustainable Agriculture and Forestry program.

Ginseng is inseparable from Chip Carroll’s life in more ways than one. The tattoo on his calf reflects his dedication to the plant and keeping it growing. Photo by Arlene Reiniger, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives Carroll settled down to raise his family in the area, continuing to work with Rural Action and United Plant Savers, and is always learning more about ginseng. Many problems beset ginseng populations in Carroll’s eyes, but the average harvester is not one of them. Deer browsing and loss of habitat from industry are concerns, along with poor conservation policies for endangered plants.

However, having monitored state forest populations of ginseng for many years, he admits he often writes in his annual reports that “the biggest threat to ginseng in the national forests is the Forest Service” and points to projects like building recreational bike paths through the woods as some of the worst actions for vulnerable ginseng populations that the agency takes.

Chip Carroll on his experience with ginseng and conservation efforts | Read audio transcriptAlthough he has maintained “there is no such thing anymore as wild ginseng,” Carroll qualifies that statement by explaining that there has been much human intervention over the years, such as moving plants from their original locations and planting seeds throughout forests. After all, ginseng has been harvested commercially for more than two hundred years in the Appalachian region; long before that, American Indian tribes used it for medicine. It is natural that humans have interacted with and affected populations in even the most remote areas.

Ever the spokesperson for ginseng conservation, Chip Carroll promotes the plant’s wellbeing wherever he goes with a GINSENG license plate on his truck. Photo by Arlene Reiniger, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives Hunting ginseng is a multigenerational activity in southern Ohio. During the years Carroll worked as a ginseng dealer, he recalls repeat clients—a grandmother, mother, and daughter. “They had a competition to see who could dig the most root. They would be so excited to come in and see whose bag weighed the most.” His preteen son has planted his own patch of ginseng, though lately his interest in football has sidetracked his ginseng cultivation. “He’ll come around,” Carroll says.

Carroll’s hope for the future of ginseng includes a practical method of educating diggers to be good stewards; he proposes a program similar to the state hunters’ safety courses. The amount of young ginseng plants he sees during monitoring is encouraging, but Carroll is discouraged by a noticeable reduction in more mature, well-established plants.

“Ginseng is a national treasure of this country,” Carroll concludes. In his opinion, it should be everyone’s responsibility to protect it.

-

Chris FirestoneGinseng Coordinator

Chris Firestone has been the Pennsylvania state ginseng coordinator for twenty years, working as an ecological program specialist and ecological botanist with the District of Conservation and Natural Resources. She takes a holistic approach to broaden conservation efforts by emphasizing the plant’s story and uses in ecology, medicine, and culture.“I think it’s so important to tell those stories for plants, because I think that’s how we can pull people into conservation.”

Chris Firestone has been the Pennsylvania state ginseng coordinator for twenty years, working as an ecological program specialist and ecological botanist with the District of Conservation and Natural Resources. She takes a holistic approach to broaden conservation efforts by emphasizing the plant’s story and uses in ecology, medicine, and culture.“I think it’s so important to tell those stories for plants, because I think that’s how we can pull people into conservation.”In her twenty years as Pennsylvania state ginseng coordinator, Chris Firestone has defined the “best and worst” parts of her job. “The best part is being able to work towards conserving important species” like the threatened and endangered plant populations she manages throughout Pennsylvania. The worst part “is trying to figure out how to make the best decisions for a plant for conservation from now and into the future.”

The passion Chris has for her job and the plants that she works to protect stems from her love of the natural world which has been shaped by influential women from her childhood. “[My grandmother] was a vegetarian and she was all about holistic health and alternative healing. She would make these green shakes for us, with weeds that she knew, which were edible. She picked them from her yard and put them in a blender. My mom was an environmental education teacher. So being outdoors and learning about the environment, I grew up doing that.”

Chris Firestone works to conserve important species every day, sometimes from the field, but often from the comfort of her office. Photo courtesy of Chris Firestone Through life experiences, Chris found an interest in plants like ginseng, starting with an internship with the Nature Conservancy that piqued her interest in plant conservation. Realizing the importance of plants and being able to identify them leads to learning the story of the plant. These stories may include the history, medicinal and food uses, and the plants’ roles in the environment—and have the power to entice people to conserve the plants.

The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources lists ginseng as one of three plants vulnerable to population decline; the other two are yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum) and goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis). These plants are at risk due to their economic value (ginseng and goldenseal) or their beauty (yellow lady’s slipper), which attracts collectors. As a ginseng coordinator, Chris monitors yearly harvesting through quarterly and annual reports from Pennsylvania ginseng dealers that record the amount of ginseng sold in the state. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service compiles this information and shares it with CITES (Conference on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). Since the addition of ginseng to Appendix II of CITES in 1975, ginseng exported from Pennsylvania is deemed sustainable, thanks to conservation efforts and policies led by Firestone and her colleagues.

Chris Firestone holds a recently unearthed wild leek at a study site in Pennsylvania. Photo by Eric Burkhart Firestone acknowledges that there will probably always be ginseng “as long as there are people to plant it.” However, she says, “the actual wild, true ginseng that’s part of Pennsylvania’s genes” needs to be protected. To do so requires the collaborative efforts of governments and citizens to make the best decisions for ginseng.

-

Cliff and RandyGinseng Growers

Cliff and Randy (last names and exact location withheld at their request) are partners in a wild-simulated ginseng growing operation in northwestern Pennsylvania. Drawing from long-standing backgrounds in harvesting wild ginseng, they learned best growing practices by trial and error. They supply organic ginseng to domestic sellers such as Mountain Rose Herbs.“When you go out and dig it, dig it at the right time of the year, put the seeds back into the vicinity, there’s some there for the next generation. Maybe your grandkids will want to dig it someday.” —Randy

Cliff and Randy (last names and exact location withheld at their request) are partners in a wild-simulated ginseng growing operation in northwestern Pennsylvania. Drawing from long-standing backgrounds in harvesting wild ginseng, they learned best growing practices by trial and error. They supply organic ginseng to domestic sellers such as Mountain Rose Herbs.“When you go out and dig it, dig it at the right time of the year, put the seeds back into the vicinity, there’s some there for the next generation. Maybe your grandkids will want to dig it someday.” —RandyCliff and Randy both have considerable experience digging and growing ginseng, but they still learn from the forest. As Cliff observes, “Yeah, we’d go out during the season and look for it instead of getting right into it and digging it. We’d sit back, look, and say, ‘Hey, there’s these kinds of trees growing and it’s facing this way on the hill, at this elevation, you know, and it’s in this kind of soil.’”

Friends and partners for decades, Cliff and Randy have a wealth of knowledge and experience growing and harvesting ginseng. Photo by Eric Burkhart When Cliff and Randy first learned the ways of the woods as teenagers, hunting ginseng was a common activity for rural Pennsylvanians, but intentionally growing ginseng in the forest was not. Randy explains, “I decided I wanted to grow some, so I started on my dad’s property. And then when I got a little bit older, I bought my own property and kept growing seeds.” He later became a licensed Pennsylvania ginseng dealer for about fifteen years, buying roots from diggers and selling them to larger buyers.

Randy’s friend Cliff became his business partner in the growing venture. Cliff recalls, “My dad showed me what ginseng was, and we started finding it and digging it and Randy started buying it. He was the local buyer in our area, and he told us how to clean it, and dry it best for the market.” Since then, Cliff and Randy have been learning how to grow ginseng together. “Nobody told us how to plant it or anything. It was all learned mostly by Randy by planting and learning how to get it to mature.”

Video by Albert Tong

Over the years, Cliff and Randy have noticed changes in the ginseng community. Randy talks about fewer ginseng diggers in his area: “I first started buying ginseng almost forty years ago. And I would say within a five-mile radius of my house, there was probably thirty people hunting ginseng. Now I don’t know. I don’t really have anybody hunting.”

It is not only the digging community that is changing throughout their time as “sengers,” but also the forest itself. As Randy explains, there used to be “black cohosh and maidenhair fern where the ginseng likes it. Now you go up there and it’s nothing but hay-scented fern. It takes it over. Smothers it out.”

Despite the challenges that ginseng and the community face, Cliff and Randy continue to advocate for ginseng conservation and to steward their land through their respect and knowledge of the plant.

Contributor: Cathryn Pugh -

Danny LeeChef and Restaurateur

Danny Lee is a well-known chef and restaurateur of modern Korean American restaurants. He uses ginseng in dishes at his restaurants and introduces this traditional Korean ingredient to a wider American audience with some new twists.“With ginseng, if there are ways for us to implement it that have not typically been done in Korean recipes before, that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t explore it.”

Danny Lee is a well-known chef and restaurateur of modern Korean American restaurants. He uses ginseng in dishes at his restaurants and introduces this traditional Korean ingredient to a wider American audience with some new twists.“With ginseng, if there are ways for us to implement it that have not typically been done in Korean recipes before, that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t explore it.”Chef Danny Lee, owner of the popular Washington, D.C., area restaurants Mandu, Anju, and Chiko, has had a long relationship with ginseng. His first contact with the root came in his youth when his mother used ginseng-infused hanyak 한약 (traditional Korean medicine) to treat a medical condition he had as a child. She referred to ginseng as the “milk of the soul,” and although he did not enjoy the taste, it helped improve his appetite. Even now, Lee uses ginseng at home to settle his stomach, aid his digestion, and boost his metabolism and energy levels. Lee observes, “At home, we drink a lot of ginseng tea, especially in the winter. It is great for the immune system and it provides that good energy where I don’t dip and crash too much, like if you drink a pot of coffee in the morning.”

Danny Lee and his mother, Yesoon Lee, prepare a dish at Mandu, their first restaurant in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of LeadingDC Lee has used ginseng in a number of ways on his menus as well. Lee and his mother served a ginseng-and-honey tea gratis to their customers when they first opened Mandu in 2006. However, they stopped serving it after a couple of months due to the unpopularity of the drink. “We thought it would be a fun, kind of quirky way to introduce small aspects of the Korean culture subtly into Western society, but after a month people were like, ‘What are we drinking?’” Lee recalls.

Danny Lee’s version of samgyetang, made with ginseng, jujubes, and sweet glutinous rice, is available at Anju restaurant. Photo courtesy of LeadingDC Washington, D.C., customers may not have been ready for ginseng at that time, but Lee knows that American palates have changed and have become more “adventurous” when it comes to Korean food—thanks to the popularity of samgyetang 삼계탕, a ginseng chicken soup served at his restaurant Anju. Although Lee uses the same ingredients as the traditional version, he prepares the rice separately from the chicken, making it into a rice porridge that is fortified with a stock that has “tons of ginseng in it.”

Lee suggests that the popularity of the dish is due not only to the “harmony” of flavors, which helps ease the diner into the strong taste of ginseng, but also because Americans have become more health conscious in recent years. Since the pandemic, Lee thinks more about the connections between body and food. “Korean food is honestly medicine. We want to explore how to implement some of these medicinal roots, ginseng included, into our cooking a bit more in a subtle way, whereby eating, you can get a delicious dish, but it is actually boosting your immune system a little bit.”

Danny Lee cooks in the kitchen of Chiko, one of his Chinese Korean restaurants. A fourth Chiko restaurant recently opened in Bethesda, Maryland. Photo courtesy of LeadingDC Lee also plans to introduce more ginseng-infused dishes and drinks to his menu. For Lee, the challenge is taking this “uniquely Korean, a very ubiquitous Korean root, that is kind of interwoven with society,” and finding ways to make it “more Korean” by subtly using it throughout his cooking. Even though it is not an easy task, Lee believes that it is important to “carry on a legacy that promotes some of the beauty and health aspects of Korean cuisine, ginseng being on the top of that list.”

Two Samgyetangs | Video by Albert Tong

Contributor: Grace Dahye Kwon -

Doug ManningBiologist and Conservator

Doug Manning is a biologist for the National Park Service at New River Gorge National Park, Bluestone National Scenic River, and Gauley River National Recreation Area. He oversees ginseng conservation projects and educates the public about the plant. He grows ginseng and other native edible plants as a pastime.“Here in southern West Virginia, we’re really in the heart of Appalachia, and as anyone connected to ginseng knows, you cannot disentangle Appalachia and how fundamentally important ginseng has been to this area.”

Doug Manning is a biologist for the National Park Service at New River Gorge National Park, Bluestone National Scenic River, and Gauley River National Recreation Area. He oversees ginseng conservation projects and educates the public about the plant. He grows ginseng and other native edible plants as a pastime.“Here in southern West Virginia, we’re really in the heart of Appalachia, and as anyone connected to ginseng knows, you cannot disentangle Appalachia and how fundamentally important ginseng has been to this area.”Doug Manning enjoyed spending time in the woods behind his grandparents’ house when he was growing up in Pennsylvania. In college, he developed a passion for ginseng while studying dendrology—the science of trees—under prominent ginseng expert Dr. Eric Burkhart at Penn State University. “I was really fascinated by his knowledge base and wanted to get involved in understanding foraging better.”

Manning first found ginseng in the wild while exploring some forest lands owned by the university. “It’s kind of like a game. I can kind of gauge what the soil conditions are from a chemistry perspective based on the plants growing there.”

Poaching is always an issue with ginseng on public lands, one that Manning and the law enforcement officers he works with take very seriously. “Our law enforcement officers arrest ginseng poachers every single year. Unfortunately, it is always a losing battle as we are only going to catch so many poachers.”

Additionally, Manning has another concern. Illegal farming of ginseng on public lands may result in the introduction of non-local ginseng stock, the cheapest and most plentiful of which are seeds from ginseng farms where seed provenance is uncertain. This means that local ginseng could crossbreed with ginseng that evolved hundreds of miles away, possibly resulting in the loss of important genetic adaptations that have helped it survive in its West Virginia habitat for generations. Manning believes it is important to preserve those native genetics by preventing poaching and illegal forest farming on National Park Service lands.

Manning advocates for the practice of forest farming on private land. “It can be a really cool concept for integrating agricultural and ecological principles into land management.” Several years ago, he and some friends purchased a forest plot, which they use for hunting and growing goldenseal, bloodroot, ostrich-fern, blue cohosh, black cohosh, ramps, chestnuts, pawpaw, persimmons, and ginseng.

“That’s part of how I became familiar with some of the seed sourcing for it.” Growing ginseng helps Manning “speak other folks’ languages” as well as to empathize and connect with how people feel about ginseng.

Manning also advocates for sustainable ginseng farming in West Virginia. “Aside from a species becoming listed under the Endangered Species Act, we don’t really have a good way of being forced into a concerted effort in conservation measures for single taxon [one species and sometimes its close relatives]. Ginseng is a good one for land managers to take on as an opportunity to try and create more coordinated and regional efforts to protect and conserve the species. I hope that it becomes its own catalyst to doing that kind of work across boundaries before we get to the point where we’re concerned about its viability in the long term as a species.”

With Manning watching over them, the hills and bends of the New, Bluestone, and Gauley rivers will likely stay rich with ginseng.

Contributor: Graydon Monroe -

Edward BurlettSouthwest Regional Supervisor, Office of Plant Industry Services,

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Edward Burlett is the regional supervisor for the southwest region of Virginia for the Office of Plant Industry Services in the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. He inspects and certifies harvested ginseng and oversees agricultural inspectors who certify harvested ginseng for dealers, necessary for the legal export of ginseng.“If we don’t regulate ginseng harvests and ensure that we’re not overharvesting, there will not be ginseng for future generations, and we don’t want that to happen.”

Edward Burlett is the regional supervisor for the southwest region of Virginia for the Office of Plant Industry Services in the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. He inspects and certifies harvested ginseng and oversees agricultural inspectors who certify harvested ginseng for dealers, necessary for the legal export of ginseng.“If we don’t regulate ginseng harvests and ensure that we’re not overharvesting, there will not be ginseng for future generations, and we don’t want that to happen.”When Edward Burlett moved from California to Virginia, he knew a lot about plants from working in the greenhouse industry but very little about ginseng. Seventeen years ago, he started as an agricultural inspector in the Office of Plant Industry Services for the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS). Now, he is the regional supervisor overseeing ginseng certifications for Southwestern Virginia, which produces most of the ginseng in the Commonwealth.

The thin “neck scars” indicate the age of the plant, so these ginseng roots (in the collection of Edward Burlett) are old but not very large—as indicated by their size relative to the quarter. Photo courtesy of Edward Burlett Because American ginseng is listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), all sales must be closely regulated. Burlett explained the process by which an inspector certifies ginseng for a licensed dealer: “Dealers will contact VDACS requesting an appointment. We arrange the meeting with the ginseng dealer. When we meet with the dealer to certify their ginseng, we inspect the ginseng to make sure that the ginseng is what the dealer claims it is.” Then the inspector weighs a representative sample of the harvested ginseng, conducts a root count, ages the ginseng, records the data, and closely reviews the dealer’s paperwork for accuracy.

Burlett explains, “We verify that if their records say they bought forty-three pounds, we know we have forty-three pounds here to be certified.”

These ginseng roots could not be certified because they are underage. According to regulations, ginseng plants must be at least five years old to be legal for trade. Photo by Edward Burlett Most dealers strive to comply with ginseng regulations and act as an extra level of scrutiny for ginseng diggers to ensure that roots are harvested legally. However, some dealers may not be as diligent about following regulations. For example, in one memorable inspection, Burlett noticed some underage roots and set them aside, explaining that the dealer needed to be more careful about buying underage roots because they would not be certified. As he continued to inspect the ginseng, the dealer’s wife suddenly grabbed the underage roots, stuffed them into her mouth, and devoured all the evidence of illegal activity.

Fresh ginseng roots are called “green.” When dried, they lose about two-thirds of their weight. Photo by Edward Burlett Burlett and his inspectors “want a continuous crop of ginseng; we want it to survive and flourish in the forest, so it’s important that people learn and understand how to properly harvest the ginseng so that we don’t lose it.” The watchful eyes of the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services help to ensure the sustainable harvest of wild ginseng in the Commonwealth in accordance with CITES and state law.

Contributor: Graydon Monroe -

Emma Lucy BraunBotanist and Ecologist

Of the seventy-five specimens of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) collected for the Smithsonian’s National Herbarium, only one came from a woman. That woman was Emma Lucy Braun (1889–1971), who, at age fourteen, collected this specimen in 1903 in Spring Hill, Ohio.“Only through close and reverent examination of nature can humans understand and protect its beauties and wonders.”

Of the seventy-five specimens of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) collected for the Smithsonian’s National Herbarium, only one came from a woman. That woman was Emma Lucy Braun (1889–1971), who, at age fourteen, collected this specimen in 1903 in Spring Hill, Ohio.“Only through close and reverent examination of nature can humans understand and protect its beauties and wonders.”E. Lucy Braun devoted her life to the study and teaching of plant ecology and conservation, earning a master’s degree in geology and a PhD in botany from the University of Cincinnati at a time when women typically did not follow this career path. Even before attending university, she began collecting plant specimens, including a four-pronged ginseng plant collected in June 1903 before the red berries appeared, which then made its way to the Smithsonian’s National Herbarium.

Growing up in Cincinnati with parents who encouraged observation and documentation of the outdoor environs, Braun and her sister Annette started early on what would become distinguished careers in botany and entomology, respectively. Decades of research trips by the sisters took them deep into the forests of the Appalachian Mountains throughout Ohio and Kentucky and covering lots of ground.

The sisters traveled approximately 65,000 miles in their explorations of deciduous forests of the Eastern United States; Annette claimed they walked twenty-four miles in one day. Braun writes of enlisting local people to find paths through the woods and even skirting illegal whiskey stills hidden deep in the Kentucky woods during Prohibition. One can only imagine how many ginseng plants they may have encountered during those excursions.

The Smithsonian’s National Herbarium includes this Panax quinquefolius L. specimen, American ginseng, collected by Dr. E. Lucy Braun on June 25, 1903, in Hamilton County, Ohio. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian’s National Herbarium A trail blazer in many ways, Braun was a tireless and dedicated conservationist and ecologist who expanded plant ecology into an academic discipline, taught for many years, and mentored countless students. She made important contributions to the literature in her field, culminating with Deciduous Forests of Eastern Northern America (1950). The book describes the relationships between organisms and their environments, as well as their relationships to each other—at the time a revolutionary approach to the field. Recognition for her work resulted in many awards and recognitions, including appointment as the first woman president of the Ohio Academy of Science, the first woman president of the Ecological Society of America, and named by the American Botanical Society as one of only three women among the Fifty Most Outstanding Botanists.

Braun’s formidable plant collection grew to 12,000 species from her youth to the time of her death in 1971. The University of Cincinnati houses most of her collection and other archival materials about her work and life, but the Smithsonian is fortunate to have some 7,730 dried plant specimens that Braun collected over her lifetime, as well as an album of photos from her field excursions to the Appalachian region. Curiously, it contains only the one ginseng specimen.

A page from E. Lucy Braun’s photo album shows some of the places she and her sister visited while conducting research. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives In a 1935 speech to “Save the Big Trees” on Leatherwood Creek, Perry County, Kentucky, Braun asks, “Why not save a piece of your native country, your native state, in its original condition as a monument to the original beauty and grandeur of your forests, just as you save an historical shrine?” Lucy Braun’s dedication to preserving and protecting forests and nature has made it possible for American ginseng and other forest medicinals to continue to thrive in their natural environments.

-

Eric BurkhartAppalachian Ethnobotanist

Eric Burkhart’s relationship with American ginseng evolved from a pastime to become his main area of research for the past twenty years. He promotes ginseng conservation through public outreach, academic research, and educational programs.“We all play a role in making sure that we’re asking the right questions, that we’re educating ourselves as a ginseng consumer or producer about how to act in the best interest of not just our own self-interests, but the plant’s interest.”

Eric Burkhart’s relationship with American ginseng evolved from a pastime to become his main area of research for the past twenty years. He promotes ginseng conservation through public outreach, academic research, and educational programs.“We all play a role in making sure that we’re asking the right questions, that we’re educating ourselves as a ginseng consumer or producer about how to act in the best interest of not just our own self-interests, but the plant’s interest.”The human connection to plants is what drives Eric Burkhart’s research interests. He grew up in western Pennsylvania with an interest in the outdoors, including ginseng “hunting.” He attributes a summer-long trip to Central America, where he conducted ethnobotany fieldwork while pursuing his undergraduate degree, as the inspiration for his decision to move back to Pennsylvania and study Appalachian non-timber forest products.

Burkhart now focuses on the medicinal and cultural uses of several important native Appalachian forest plants. He recalls, “I saw that the same scientific questions and conservation needs that I was trying to address in my international work were also true closer to home, in Appalachia.” And so began his two-decade fascination with American ginseng and its inextricable cultural ties to his own region.

Burkhart has been conducting an annual survey of ginseng sellers for the past ten years to gain insight into planting and trade within the state of Pennsylvania. Results of the survey help gauge how much ginseng is harvested each year, a necessary measure to track exports of the state-listed vulnerable plant. He also tracks its sources and whether it was wild, cultivated, or somewhere in between.

Eric Burkhart is a professional botanist and ethnobotanist with expertise in identifying plants in the field, which is one of many skills he teaches at Penn State University. Photo courtesy of Cathryn Pugh The title “wild,” if intended to mean untouched or separate from human interaction, is a misnomer, according to Burkhart. He observes, “There are very few populations out there in the United States, at this point in history, that have not been impacted by people on an ongoing basis, either through harvesting, harvesting and replanting, or establishment of new populations.” Due to its vibrant cultural significance, the strategies used to conserve ginseng differ from that of other wild plant species. In fact, Burkhart goes on to speculate that “if we didn’t start to cultivate American ginseng a hundred years ago, it probably would be completely gone.”

The relationship between cultivated and wild ginseng is even more complicated. A market has developed around cultivated ginseng, which has helped wild ginseng conservation. Yet, as Burkhart explains, “There is still a persistent demand for wild because of the demand based within traditional Chinese medicine and other cultural predilections.” This demand for “true wild” ginseng creates a vast dollar value difference, still attracting many harvesters to search for ginseng in the wild and sometimes to steal wild ginseng from public and private lands.

Eric Burkhart shares red, ripe ginseng berries as he discusses ginseng cultivation. Participants of this public program planted the berries near the existing mature plants, as is good stewardship practice. Photo by Betty Belanus, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives Many people continue to dig and sell wild roots legally and ethically, and to steward populations along the way. Planting seeds within ginseng populations or establishing new patches on one’s own land promotes “conservation through cultivation,” a strategy that Burkhart encourages as one way to relieve the harvesting pressure on wild ginseng.

Burkhart’s work inspires those who care about American ginseng to share responsibility for and contribute to its conservation. His work helps educate ginseng enthusiasts about best practices in keeping with the plant’s best interests. “We need to find that middle ground of connections and be able to figure out how we can collaborate and work together,” Burkhart hopes. “We all have an individual role to play when it comes to sustaining this resource.”

Contributor: Cathryn Pugh -

Fran DayDirector of Institutional Advancement, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts

Fran Day grew up in the mountains of East Tennessee, helping to support her large family and paying for her college education partially by digging ginseng. The wealth of knowledge of the woods she gained as a youth has brought a lifelong love of and respect for her native Appalachian region.“Being tied to the land, we were not like some people who could just move off and go north and work in the factories. So, my stepfather and I became bootleggers and ginseng diggers.”

Fran Day grew up in the mountains of East Tennessee, helping to support her large family and paying for her college education partially by digging ginseng. The wealth of knowledge of the woods she gained as a youth has brought a lifelong love of and respect for her native Appalachian region.“Being tied to the land, we were not like some people who could just move off and go north and work in the factories. So, my stepfather and I became bootleggers and ginseng diggers.”For several generations, members of Fran Day’s family were coal miners and farmers, and she is quick to note the hardships they endured. “We lived a subsistence existence. We made our own clothes, we grew our own food, we lived on top of a mountain on a farm, and it was an interesting way to grow up. We didn’t have running water or electricity; we lived in a house where you put rags and paper in the cracks to keep the bugs and the snakes from coming in.”

Fran Day’s maternal grandfather was Fred Elmore, a sheriff and Baptist preacher. The folklore around Elmore says that he rode with Jesse James, although there is no proof. The Blue Diamond Coal Company hired Elmore to come to Westbourne, Tennessee, and establish a church and a jail. Photo courtesy of Fran Day Day’s stepfather first introduced her to ginseng digging after the coal mine where he worked closed in the 1950s. Tennessee remained a “dry” state, even after Prohibition ended, so he also taught her the art of making moonshine while avoiding the law. One trick was to bake bread during the process so that the smoke and aromas would detract from the real business at hand. Made in proper barrels with a copper still, and with homemade cornmeal and malt, the family’s moonshine was among the best in the area.

Fran Day on growing up in Appalachia and digging ginseng with her stepfather | Read audio transcriptDescended from “mountain people,” Day’s stepfather was familiar with the lay of the land. He and Day dug ginseng in season, sometimes visiting the closely guarded and secret patches in parts of the Cumberland Plateau nicknamed “No Business” because, according to Day, people had no business being there amid moonshine stills in operation. Families in those parts ensured that the plants thrived from year to year because they knew all too well that the ginseng patches provided much-needed income.

Fran Day and her granddaughter Jasmine on the Arrowmont campus. Photo courtesy of Fran Day Day and her stepfather knew instinctively what to look for. “There were all kinds of things you had to look at, like the color of the leaves, the size of the stem, where the new growth was, where it was in the patch; ideally it would be in the center what you would leave and you would take from around the edges. But, of course, that wasn’t always possible because sometimes it didn’t grow according to the laws of humans, it grew according to the laws of ginseng. We were digging what we could find as much as we could without harming the patch.”

To safeguard this part of their livelihood, Day and her stepfather were very careful to conserve the patches. They left the older plants to propagate and the younger ones for the roots to grow and mature; they never took more than half of a patch and painstakingly dug to get the entire root. Day and her stepfather did not revisit patches in successive years unless there were enough plants continually growing there. “But sometimes we would come back, and a raider would be through and the patch would be gone. And as time went on, many of the patches had gone.”

Fran Day (then Fran Oakes) joins her fourth-grade classmates for a photo. Fran is in the second row, second from the right. Photo courtesy of Fran Day Day credits her current position with the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts to her subsistence upbringing, making moonshine, digging ginseng, and earning money any way possible. As an institution that has taught Appalachian craft since 1912, Arrowmont is a welcome and calm haven just steps from Gatlinburg’s heavily touristed main street where shops and restaurants perpetuate the “hillbilly” stereotype. Day takes it all in stride: “As hillbillies, we’re going to let you make fun of us all you want to, and we’re going to join right in and laugh, but then we’re going to take your money to the bank.”

-

George Stanton and A.R. HardingEarly Figures in Ginseng Knowledge

George Stanton was one of the first individuals to successfully cultivate ginseng in the United States and is often regarded as the founder of the cultivated ginseng industry. Arthur Robert Harding wrote Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants, which is the essential bedrock of knowledge for the industry.“Anyone who has dug wild ginseng to any extent knows that... nature does not furnish a very reliable rule. We must be guided by common sense to start with, and practical experience later.” —George Stanton

George Stanton was one of the first individuals to successfully cultivate ginseng in the United States and is often regarded as the founder of the cultivated ginseng industry. Arthur Robert Harding wrote Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants, which is the essential bedrock of knowledge for the industry.“Anyone who has dug wild ginseng to any extent knows that... nature does not furnish a very reliable rule. We must be guided by common sense to start with, and practical experience later.” —George Stanton

“The time is ripe for those who are willing to take up this work.” —A.R. HardingWidely recognized as the founder of the cultivated ginseng industry, George Stanton was a retired tinsmith and avid “senger.” In 1885, even though a friend described him as frail and in poor health, Stanton was still harvesting ginseng in the wild when he relocated some of those plants to his own garden. Through meticulous observation and force of will, he eventually achieved truly impressive root harvests with forest seed beds and a lengthy maturation period.

This portrait of George Stanton appeared in his obituary. Photo courtesy of Special Crops (1908). Working on his root beds helped Stanton regain his waning health and embody his catchphrase, “wear out, not rust out.” He later became the first president of the New York Ginseng Growers Association (est. 1902) and frequently contributed columns for a variety of publications, such as Special Crops, the association’s official journal.

In that very journal in 1908, appeared Stanton’s obituary, written by his close friend, J.K. Bramer, who described Stanton’s devotion to his craft: “The tenderness with which he would handle the little roots, which he called his ‘babies,’ would remind you of the care a mother would show in the tucking away of a real baby in its little bed.” Those little beds grew to encompass a large artificially shaded garden and an even larger forest nursery, which thrived under Stanton’s tending.

The original cover of Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants by A.R. Harding. Photo courtesy of Fur-Fish-Game Shortly after Stanton’s death, his contributions appeared in Arthur Robert Harding’s Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants (1908), a seminal publication that helped elevate the industry to new heights. Harding was a mysterious character, whose first business venture began at fourteen, when he was buying and selling furs in the Ohio River Valley. His avid outdoorsmanship and entrepreneurial spirit may have led him to hunting wild ginseng, which like hunting or trapping animals, has been a money-making endeavor since the eighteenth century. Cultivating the elusive and notoriously finicky forest plant takes years of patience and husbandry skills, which Harding’s publication explains for those who wish to try.

Seemingly an educator at heart, Harding also ran three of his own publishing companies alongside his fur business and outdoor adventures. His other publications centered on hunting, fishing, and trapping, but Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants remains one of his most popular and was re-released twice in his lifetime.

Arthur Robert Harding wrote Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants, a seminal work published in 1908. Photo from Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants By the time of his death in 1930, A.R. Harding was a household name alongside George Stanton in the niche world of ginseng cultivation. Their mutual colleague, Charles M. Goodspeed, published and edited much of their works, including a final version of Ginseng and Other Medicinal Plants in 1936. Stanton and Harding helped set the stage for American ginseng cultivation, which now is a multi-million-dollar industry.

Contributor: Chris Babbitt -

Iris GaoGinseng Researcher and Plant Molecular Biologist

Iris Gao farms American ginseng in a laboratory. Her enthusiasm for American ginseng started in the lab but has reached far beyond science—even to depict the plant in handmade quilts.“The herb is from the local area and is so important to local economy and culture. For those reasons, I think American ginseng is worth studying.”

Iris Gao farms American ginseng in a laboratory. Her enthusiasm for American ginseng started in the lab but has reached far beyond science—even to depict the plant in handmade quilts.“The herb is from the local area and is so important to local economy and culture. For those reasons, I think American ginseng is worth studying.”Since 2011, Iris Gao has been at Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU) researching herbal medicine, specifically the biological and pharmaceutical properties of medicinal plants. While studying the authenticity of herbs in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) with collaborators in China, she realized American ginseng’s potential. Further research revealed that Tennessee is the best place to study this plant because so much wild American ginseng grows there. She was in the right place.

“TCM believes that the effect of an herb is related to its geological source,” Gao explains. “Each herb has its own authentic origin, and the herb that comes from that region is the most effective. The best Asian ginseng would be those [plants] from the Changbai Mountains [on the Chinese/North Korean border]. And if you want to study TCM herbs here in the United States, there is only one geo-authentic herb you can find—American ginseng, Panax quinquefolius.”

A petri dish in Iris Gao’s laboratory shows the early stage of micropropagation when tissue samples from ginseng plants grow in culture. Photo by Sam Lindemann Gao and her team concentrate their research on the micropropagation of ginseng plants, and possible uses of ginseng leaf. In conducting her research, Gao has collaborated with other departments at MTSU, with farmers and ginseng dealers throughout Tennessee, and with research organizations in China.

Growing wild-simulated American ginseng (using the natural wooded environment with shade and nutrient exchange between plants) could become a major source of income for Tennessee forest farmers. But it takes seven to ten years before the slow-growing ginseng roots are large enough to be harvested if started from seed. In her lab, Gao uses tissue samples from a mother plant, producing a large number of rootlets that shorten the growing time at a lower cost than other commercially available rootlets.

“By doing this, the almost three-year germination and shooting period of ginseng can be shortened to just a few months.” Micropropagation also maintains the ginsenosides found in wild American ginseng, the pharmacologically active compounds in ginseng which make it so valuable.

After appearing in one of Iris Gao’s publications in 2020, this photo of a wild ginseng plant inspired a quilt she made while isolating due to COVID-19. “They are both Appalachian traditions passed from one generation to the next. They both need patience–a lot of patience–to become what they are eventually admired for. And, finally, they both require perseverance.” Photos courtesy of Iris Gao Gao has also been studying the ginsenosides in the leaves of American ginseng plants. Currently, ginseng root is mainly used for medicine in TCM. If the leaf is proven to be as pharmacologically active as the root, it could help conserve endangered ginseng plants. “We are exploring the effectiveness of using ginseng leaf as medicine. In this way, we can avoid destructive harvesting. You don’t need to dig out the whole plant, you can just collect the leaves.”