When I was a teacher at the University of Wyoming, I taught a “Great Books” course, which was funny because I went to music school and had read none of the syllabus coming into class. But I stayed a week ahead of the students, and it turned out to be one of the best teaching experiences of my life. Shepherding twenty-first-century Wyoming freshmen through outdated canon was slow, hard work, but some of those texts stick with me still.

This week, two ancient scenes kept coming to mind:

“[Creon] has proclaimed none may bury [Polyneices] but leave him unwept, entombed, a rich sweet sight for the hungry birds beholding.”

—Antigone

“… on the wall she stopped and looked, and was ware of him as he was dragged before the city.”

—The Iliad

Before the victims of the Atlanta killings could be mourned as individuals who embodied worlds beyond their races, genders, or jobs, before their names were read, they were dragged like Hector across my feed in their worst moment in large part to support my political cause. I fear that the quick catharsis of our instant reactions smothers potential long-lasting energy which we need to sustain real change. While there is actual good coming from this moment (money being donated, mainstream conversations), I wonder how many millennials and Gen Z folks will get burned out by the rapidity of their reactions, the quick swells of their rage, and the almost fetishistic latching onto other people’s suffering? You do not necessarily care less because you are quiet.

In Wyoming, there is a place called Rock Springs. I stop there every time I drive that stretch of I-80. In 1885, at least twenty-eight Chinese miners were slaughtered by a white mob. The entire Chinatown was razed to the ground, and the survivors were run out of town. It’s a story that even friends of mine from the area were never taught in school.

In the Pacific Northwest, where I live now, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was pockmarked by a string of anti-Asian riots and massacres inflamed by economic tensions and state-sponsored, racist immigration laws. The other day, my partner Emilia pointed out a curious spot along the Snake River called “Chinese Massacre Cove.” Sadly, Atlanta is nothing new. It’s the latest skip on a broken record, the most recent massacre in a long, bloody, forgotten history literally written into our maps.

Wyoming was the first place I felt at home. Even though I returned east to get my PhD, I came back to Laramie every summer to teach, thinking someday I would move back, buy some cheap land, and settle down. But in 2017, toward the end of teaching what would become my last course at UW, I had a rough experience at a bar called The Library—the same building where Matt Shepard met his murderers that night in 1998. It was just after lunch, and as I was leaving through the front of the building, a thick-necked, very large man came up to me. He started shouting in that racist, fake Chinese gibberish which I am unfortunately well acquainted with, spitting and aggressively pointing his finger in my face. Surprised and embarrassed, I stood still. He moved closer and closer. Sizing him up, I knew I wouldn’t win the fight if it came to blows, so I walked away to the decaying sounds of his abuse. No one intervened or said a word.

The Library incident triggered old moments of physical violence and racial slurs I had been on the losing end of since I was five years old growing up in Tennessee. It took me back to playground fights. It reminded me of all the ignorant nicks of racial insensitivity suffered from friends and enemies alike, as well as scarier altercations in recent years. There were at least three other incidents in Wyoming where someone came at me with openly racist insults, but this felt different. Maybe it was the person in the White House at the time. Maybe it was my own academic obsession with racial trauma. Maybe it was because this went down in broad daylight in a place I loved. After that incident, I no longer felt at home in Wyoming.

And I hate that.

I hate that fear. I hate the paranoia that arose from that moment and which is arising nationwide amid the swell of hashtags and short ALL CAPS protest tweets. There are real inexcusable acts of violence and racism being perpetrated against the Asian American community, and this needs to be taken seriously. But I also don’t want to be paralyzed by my newsfeed into thinking I might be attacked at any moment, because that is not the case. When I breathe and calm down, I know the overwhelming majority of Wyomingites and Americans are good people who need better education. I pray that this is the moment to finally bring about some long overdue awareness.

#StopAsianHate is useful to gain attention, but, like all hashtag activism, it’s incredibly vague. Atlanta should be a catalyst for deeper historical discussions which illuminate and unpack how long this “anti-Asian” hate has really been going on, not just on the individual level but through our state policy: Chinese Exclusion (1882), the Johnson-Reed Act (1924), Japanese American incarceration (1942), and uninterrupted American military intervention in Asia since World War II. It is also important to highlight the circumstances which have historically contributed to anti-Asian discrimination: economic competition, black-white wedging, sexual fetishization, disease scapegoating, overseas tensions, and fear of immigrants. These topics are important to learn about not only to place Atlanta in context, but also to prepare for a future in which tensions between China and the United States could very well define global politics for the next century. For the sake of all of us who “look Chinese,” it’s important that Americans learn from the past.

I also hope that this moment can both strengthen and add nuance to the term “Asian American.” The relatively recent invention of the “Asian American” was concocted by mostly college-educated Chinese and Japanese American activists in the 1960s and ’70s who idealized a pan-Asian solidarity movement. Ironically, this was centered around protest of the war in Vietnam, my mom’s homeland, and a country which Japan and China have both historically conquered and oppressed.

Solidarity is good because it is politically useful, but at the same time, disaggregating the data and understanding the diverse group that is Asian America is important. While most Indian, Chinese and Japanese Americans make more money than the average U.S. household and hold more college degrees, a large percentage of Pacific Islanders and Southeast Asians struggle with poverty and are often left out of the discourse surrounding Asian America. Just as Atlanta should spur interwoven, sustained conversations on white disenfranchisement, sex work, gun control, and misogyny, we also have to think about which Asian Americans are most susceptible to crime, anti-Asian, “hate” or otherwise. We must consider class, immigration status, and countries of origin in Asian American discourse.

Any ascending Asian American political movement needs to understand that those most at risk in “our” community—of violence, of deportation, of poverty—are not the college-educated, largely West Coast East Asian activist leaders who speak the loudest and control the discourse. I hope that this movement, formed around protest of a war in Southeast Asia, starts channeling their energy and, more importantly, their considerable wealth to helping other AAPI communities, just as they have so successfully helped themselves.

Empathy, change, representation: these things require time, even for the best among us. How long did it take for the genuinely fine people at Smithsonian Folkways to put out the Asian Pacific America Series? How long did it take me to unravel a lot of the racism, homophobia, and misogyny I grew up with in the South? A decade of graduate school and touring the world, and I am still a very flawed work in progress. Ask any number of former friends, classmates, and bandmates how hurtful and tone deaf I’ve been at times in my past. But I own that, and we, as Americans, have to own our often-regrettable past. We all have work to do. Slow, thoughtful, mistake-laden work.

But breadth and space are not du jour in today’s all-caps ACTIVIST culture. Hashtag social justice has reached the point of wallpaper ubiquity. This turns a lot of people off, including myself. Social change, the fight for equity—this is necessary work, but the overwhelming repetition and volume is divisive. I can’t scream at rallies anymore. That’s why I sing. I’m more interested in working in a gentler way. And if you are too—and I hope you are because we need you, fellow citizen!—I recommend reading adrienne maree brown and Wendell Berry for some smart, slower, environmentally inspired takes on activism and life.

Two exceptions to my weariness of the post-tragedy social media din are my friends Phi Nguyen and Hillary Li, who are both woke AF millennials. Why they get a pass is because they back up the tweets with work that you’ll never see or hear about, work that would break me. They are lawyers with Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta who offer constant inspiration. I’ve watched them tirelessly serve Asian Americans back home in the South and struggle to save my fellow Southeast Asians who came here as refugee children from cruel, inhumane deportations. My heart broke for these women knowing that these shootings happened in their backyard. So, let me end by quoting Phi:

“Today I am grieving the deportation of 33 Vietnamese refugees on Monday and the murders of eight people, six of them Asian American women, on Tuesday. When we talk about anti-Asian violence, let’s include structural and State-sanctioned violence too. That the Asian women murdered yesterday were working highly vulnerable and low-wage jobs during an ongoing pandemic speaks directly to the compounding impacts of misogyny, structural violence, and white supremacy.”

In the light of Atlanta, we need to comprehend the horrors of the past. Untangle the information. Breathe. Get beyond the slogans. Trace sources. We also need to relearn how to grieve, mourn, and bury our dead, remembering that in most of these senseless tragedies we do not know these people, and therefore we do not know their politics or if they would be comfortable being on display in their worst moment for my cause, no matter how righteous I believe my cause to be. Find a moment of silence for these dead you do not know but seek to invoke. Perhaps even give it a few days. And in that time of reflection, pick up some Thich Nhat Hanh, wisdom which has changed my life. Then, stand up and be like Phi and Hillary, or at least donate to their work.

Rest in peace Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, Yong Ae Yue, Paul Andre Michels, Delaina Ashley Yaun Gonzalez.

EDIT: And before the ink was even dry on this, RIP to the victims of another senseless American massacre.

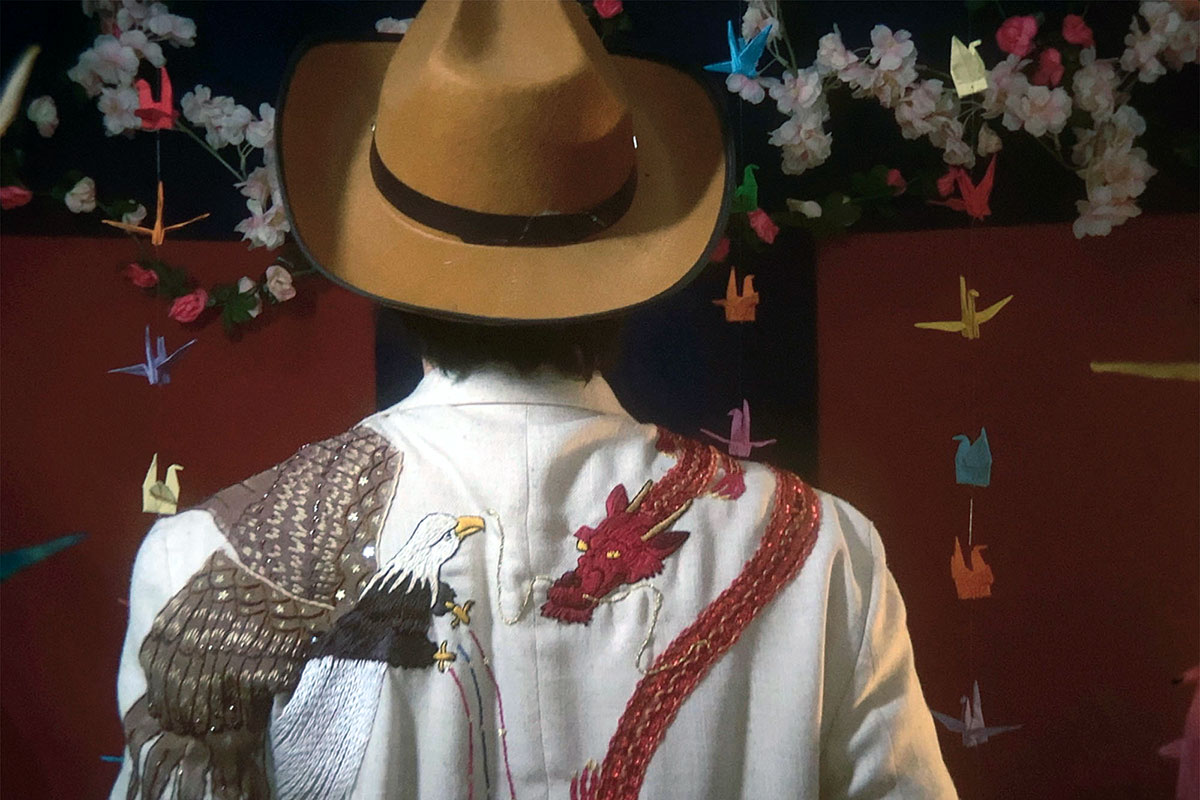

Julian Saporiti is a Vietnamese American musician and scholar who was born and raised in Nashville. He has studied Asian American and transpacific culture, as well as immigration, refugees, and twentieth-century imperialism in Southeast Asia while working on his PhD at Brown University. As No-No Boy, his latest album, 1975, which comprises part of his dissertation, is available on Smithsonian Folkways.