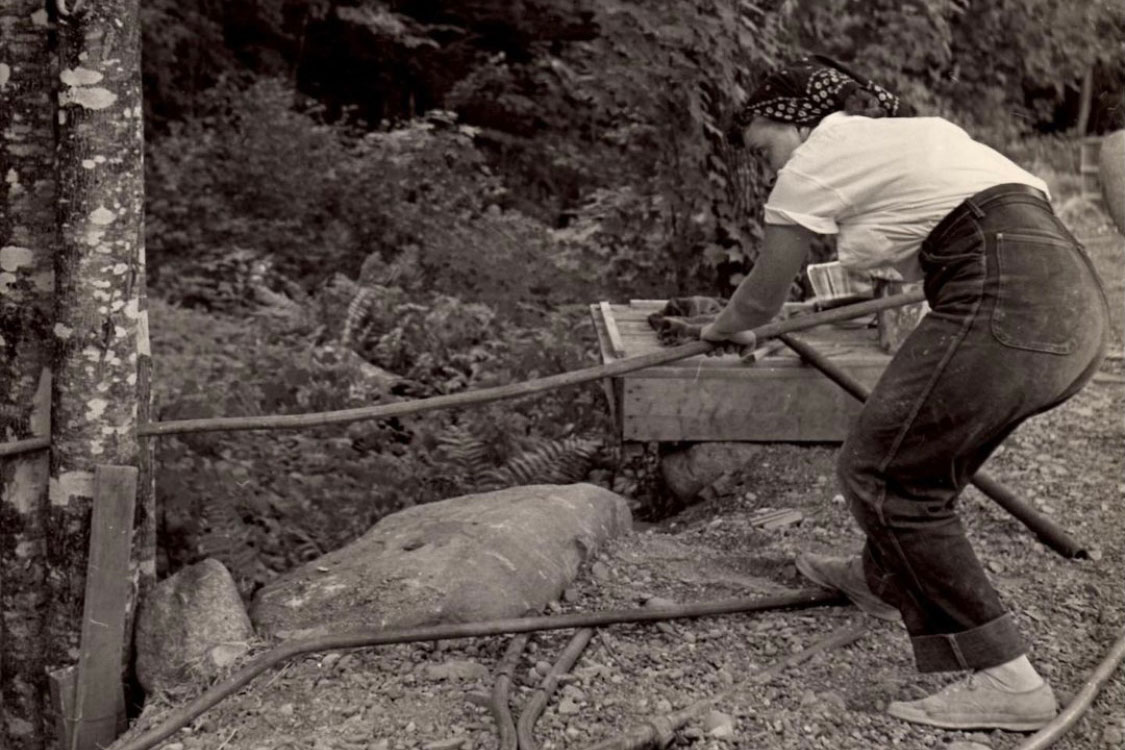

Like so many others throughout the world, I have faced tremendous loss in the past year. In February 2021, I lost my grandmother, Claire Leven—the matriarch of my family. She was a woman who was always smiling, and her infectious laughter spread to everyone she met, filling their days with joy and love. Before she became a mother, she was a sculptor who studied at Cooper Union and the Brooklyn Museum of Art School. Later, she received a Fulbright scholarship to study classical sculpture in Florence, Italy.

Claire’s magnanimous spirit and passion for life was contagious. She was my inspiration as an artist, a social activist, and a mother and grandmother who loved deeply. But despite everything I know about my grandma, there is still so much to uncover.

My grandma wasn’t only an artist, activist, and mother. She was also a Jewish woman. If she could hear me today, she would probably want me to emphasize that she was a secular Jew—which made sense for her but always made me curious about how her Jewish heritage affected her life’s journey. With so many family members lost in the Holocaust and the compounded generational trauma from antisemitism, there are many nuances to unfurl to fully understand her life and what shaped her as a person.

For years before her passing, I worked with my grandma to write down and record the details of her life for an eventual memoir. We talked giddily about writing it together, while we looked through old correspondence from her artist friends (many who were clearly in love with her). We would send our writing back and forth virtually, her emails containing pages of stories written in all capital letters.

On one sunny afternoon, we lounged on my family’s front porch as I recorded interviews with my grandma on my phone. Claire talked about her weekly trips with her twin sister and mother in Lower Manhattan to pick up gefilte fish, boiled chicken, and soup for their Friday night Shabbat dinners. She also told me that she used to draw all the time in kindergarten and how her teacher would compliment her artistic talent. And Claire loved to share the story of when she was awarded the Daughters of the American Revolution citizenship award in sixth grade in the early 1940s. Though, she was always quick to remind us that she tore up the award after learning that, in 1939, the DAR had banned Marian Anderson from performing at Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall because she was Black.

In the past couple of months since she passed away, I’ve been thinking about the ways in which I could honor her life and tell her story. I thought that I could continue our work on her memoir, but it didn’t feel right to me. It wasn’t until I heard anthropologist Lina Fruzzetti talk about her work tracing her family history that I began to fully understand how my background in anthropology could help me tell my grandmother’s story.

During the 2021 Mother Tongue Film Festival’s Anthropologists as Storytellers roundtable discussion, I heard Dr. Fruzzetti and her longtime partner and collaborator Ákos Östör speak to the value of film as a medium for storytelling and as part of their ethnographic work as visual anthropologists.

Their film In My Mother’s House (2017) tells a beautifully personal story as it unfolds in real time. It took eight years to finish, following Fruzzetti’s journey as she traces the history of her Eritrean and Italian parentage. Her story, while specific to her family’s heritage, touches on wider experiences of colonialism and displacement. During the roundtable, she acknowledged that the audience’s interest in the film is rooted not only in the ethnography of her heritage but in the relatability of the story it tells.

Hearing Fruzzetti’s story as described in the film and roundtable has shaped how I now understand the role of visual anthropology in telling stories. Inspired by her journey to uncover more about her mother’s life, I wondered how I could emulate this work and create a story that is both ethnographic in nature and honors the memory of my grandmother. Ultimately, storytelling through visual anthropology has the power to interweave intimate portrayals of individuals while also showing global trends and phenomena that impact our daily lives.

While I can’t say for certain that it was Fruzzetti’s intention to pay homage to her mother with the film, I believe it painted a complicated yet lovely portrait of family and heritage. Emphasizing the trials and tribulations of meeting new family for the first time and reconciling different and collective memories of past events, Fruzzetti and Östör’s work shows the anthropological methods involved in making ethnographic documentaries. Working to subvert colonial paradigms of anthropology, anthropologists can structure films so that they tell a narrative guided by the community collaborators whose story is being told.

Similarly, an example of this method can be seen in the documentary Texo Haxy/Being Imperfect (2018), showcased in this year’s Mother Tongue Film Festival. Texo Haxy employs this method by having both Brazilian anthropologist Sophia Pinheiro and Indigenous Kerextu filmmaker Patrícia Ferreira film each other and themselves in an experimental collaboration.

Learning about visual anthropology through the work of Fruzzetti has been a powerful experience, ultimately reshaping my view of anthropology as a discipline. The power to tell stories through ethnographic film puts anthropologists in a unique position to share knowledge. I am deeply inspired by Fruzzetti’s story about her mother, and it has ignited my interest in creating an ethnographic documentary to trace my own heritage—starting with my grandmother. My grandmother’s story deserves to be told, and I have come to realize that my position as an anthropologist and loving granddaughter will allow me to create a special piece of visual history.

As Fruzzetti stated in the panel, “Every film has a powerful story it can tell.”

Mariel Tabachnick is an intern for the Mother Tongue Film Festival at the National Museum of Natural History. She is a recent graduate from the University of Pittsburgh, where she studied anthropology, global studies, and French. This fall, she will be pursuing a master’s in visual anthropology at the University of Manchester.