The past and present of Korean skiing is situated in Gangwon Province, located in the mountainous eastern region of the peninsula. The 2018 Winter Olympics are taking place here in the South Korean cities of PyeongChang and Gangneung. However, the birth of Korean skiing occurred north of the DMZ, in a part of the province now considered North Korean territory.

It was February 1940 in the port city of Wonsan, Korea, that competitive skier Choi Hoon won silver medals for the men’s eighteen-kilometer cross-country and thirty-six-kilometer relay.

“You are the first Joseon person to reach the podium in the All Joseon Ski Championship,” a Japanese journalist told him—“Joseon” referring to peninsula now known as Korea. Despite its name, the All Joseon Ski Championship was a subcategory of the All Japan Ski Championship, and only a few ethnic Korean skiers participated, compared to 180 to 190 Japanese participants. Of course, he was excited to win the medals, but he was more proud of being the first Korean person at the podium because of the political circumstances at the time: Japan’s colonization of Korea (1910–1945).

Choi Hoon was my grandfather. He passed away two years ago at the age of ninety-one. Since the 1990s, he had been documenting the history of skiing in Korea and detailing his own skiing career. He finished writing his manuscript in the early 2000s, but as he aged and developed Alzheimer’s disease, he lost motivation to see it published and tossed his research into his closet.

After his funeral, my mother showed me his manuscript. As soon as I began reading, I got the urge to continue his work; it represents an important primary source about the development of skiing in Korea, which laid the groundwork for hosting the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea.

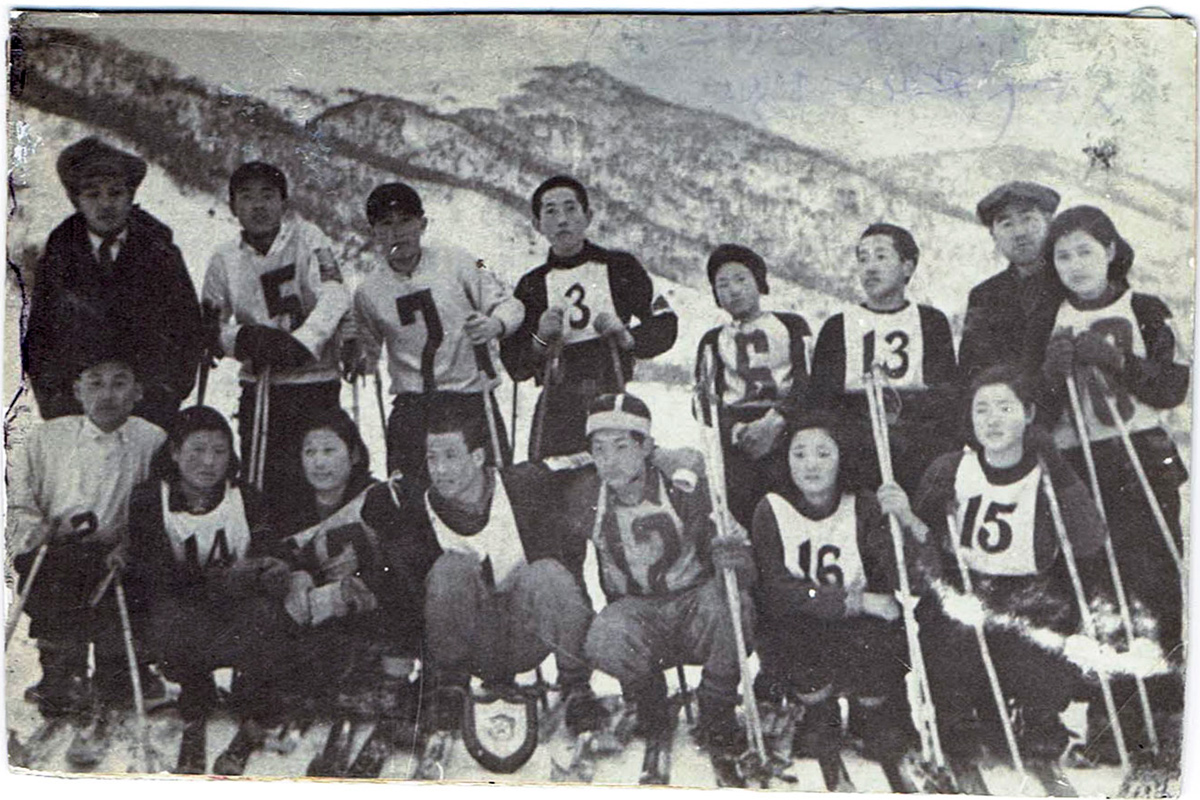

Looking through a historical and cultural lens, the unified Korean Olympic team mirrors my grandfather’s contribution to the growth of skiing in the Korean peninsula. He was one of a few people who had experienced the spread of the sport in what is now both North and South Korea. He started skiing at a competitive level in 1939, when he was seventeen years old. He joined a ski club in Sungjin, a city currently in North Korea, as its first Korean member. Unfortunately, his career halted abruptly as the club disbanded with the surrender of Imperial Japan in 1945.

Although the turmoil in the 1940s and 1950s interrupted his athletic track, he continued his passion after fleeing to what is now South Korea during the Korean War. After his escape, my grandfather became a ski coach for six years, served as a board member at the Korea Ski Association (KSA) for ten years, and was the editor of Ski Letter at KSA for twelve years.

There are many hypotheses involved in the birth of Korean skiing. In my grandfather’s manuscript, he traces the history back to the colonial period. Nakamura Okajo, one of the Japanese teachers dispatched to Korean schools in 1921, was deeply disappointed to find that modern skiing did not exist there. He formed a team at the Wonsan middle school with help from colleagues and relatives back in Japan. The team’s success encouraged the city to begin building modern facilities. In time, my grandfather’s region built its own team to compete against Wonsan.

While reading the manuscript, I was fascinated by my grandfather’s perspective on the first ski competition, held in 1929, at the Wonsan shin-poong-ri (ski facility). He chose to highlight the participation of Korean women, though the overwhelming majority of competitors were Japanese and male. What united them all was their passion for the sport. In particular, he expressed respect for the ten female high school athletes who skied the mountain in their school uniform skirts and on borrowed skis from the Wonsan middle school. Though ill-equipped, these students were the first recorded female skiers in the history of Korea.

According to my grandfather, the challenges of acquiring affordable equipment hindered the growth of skiing in the colonial period, creating ethnicity-based class distinctions within the sport. Of the estimated 6,000 skiers in Korea, only 300 were Korean. The rest were Japanese.

Following common practice of the time, my grandfather grew up with bamboo skis. He didn’t receive modern equipment until he reached competition level. After the liberation in 1945, many Korean skiers claimed gear the Japanese left behind. My grandfather’s coach gave his remaining equipment to my grandfather before repatriating to Japan.

With Korea’s independence from colonial rule, KSA made it their mission to promote skiing up and down the peninsula. By my grandfather’s count, ten facilities already existed in the north, but skiing in the south was still in its infancy.

Korea held its first national championship in 1947, and KSA kept them going all through the Korean War. After Korea was divided in 1953, KSA and my grandfather’s publication continued to promote skiing and began to engage with international ski communities.

I can only imagine the heights of his happiness in 1960 when KSA sent its first two Olympic skiers, Kim Ha-Yoon and Yim Kyung-Soon, to compete in Squaw Valley, California. Today, there are over five million active skiers in South Korea.

When my parents told me of my grandfather’s death, I was saddened that he would not be able to see the Olympics unfold in PyeongChang. Throughout his manuscript, he wrote about how he, along with other Korean winter sports athletes, hoped and fought for PyeongChang to host the games in 2018.

Now, as I watch this year’s events, my emotions are conflicted. On one hand, I feel inspired by the many athletes who have overcome various challenges and struggles. But the thought of my grandfather breaks my heart. I picture him watching every ski event, cheering for all the athletes, regardless of their nationality. In his manuscript, he wrote that he could not root solely for Koreans, nor for the most talented competitors. Rather, he cheered on those who came from underrepresented countries, who made mistakes, or who did not perform to their best ability.

My grandfather’s manuscript taught me why his empathy was imparted to those underdogs: he was one of them. He was a Joseon athlete, a colonial subject who was treated as a second-class citizen for much of his life. Even in South Korea, his accomplishments as an athlete were never fully recognized because of his North Korean origin.

Like many in his generation who personally experienced the division of the peninsula at the Korean DMZ, he wished for a unified Korea. He hoped that, one day, both South and North Koreans would create a Korea Ski Association comprised of those who would uphold the earliest objectives of KSA: “to provide the best environment to train skiers, regardless of whether they are Japanese or ethnic Korean, because sports do not discriminate against people based on race or ethnicity.”

Crystal Rie is the archival audio media conservation technician in the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. One of her resolutions for 2018 is to transcribe her grandfather’s 500-page manuscript for posterity and publication.