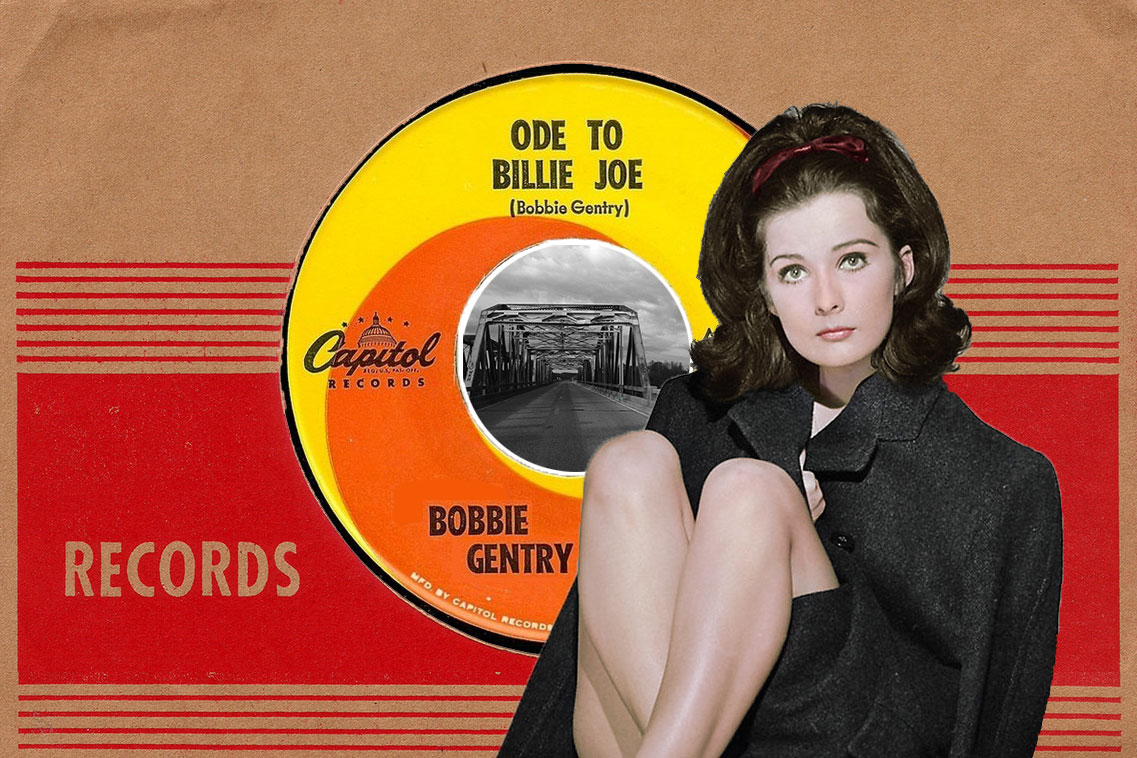

Fifty-five years ago this week, on March 13, 1967, Capitol Records acquired two songs from Bobbie Gentry, a hitherto-unknown singer-songwriter originally from northeastern Mississippi. One of those songs, “Ode to Billie Joe,” became a surprise hit that summer: reaching the top of Billboard’s Hot 100 on August 26 by displacing “All You Need Is Love” by a hitherto-unbeatable quartet from Liverpool, and remaining the number-one pop song for four weeks.

“Ode to Billie Joe” is not a folksong, which folklorists might define as a combination of words and music that circulate orally in traditional variants among members of a particular group without continual, corrective reference to a fixed source. Nor is it a ballad, which folklorists might define as a folksong that tells a story. However, “Ode to Billie Joe” contains qualities that are both folksong-like and ballad-like, and that certainly caught the nation’s ear that summer for reasons that still reverberate today.

In retrospect, the summer of 1967 seems especially tumultuous, even for a decade that has become synonymous with tumult and rebellion. On the West Coast, it was the “summer of love,” with San Francisco as its epicenter, leading Scott McKenzie to advise in another of the year’s hit songs, “if you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.” On the East Coast, the Smithsonian’s first Festival of American Folklife took place over the July 4 weekend in Washington, D.C., to document and celebrate traditional American music and crafts. However, the summer took a much darker turn in July, when long-simmering racial injustices erupted in Newark and Detroit, which prompted a national commission once more to seek the underlying causes. Meanwhile, Montreal hosted a the six-month-long Expo 67, which looked beyond both present and past to an imagined future for all humankind.

Into this ’67 cultural cauldron came Bobbie Gentry, then twenty-five years old. According to Tara Murtha’s authoritative study, she was born Roberta Lee Streeter and spent her first six years with her paternal grandparents on a farm without electricity in Chickasaw County in northeastern Mississippi. When it came time to attend school, she moved some ninety miles west to live with her father in Greenwood, Mississippi, then population 18,000, on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, near the meandering Tallahatchie River—which brings us back to the hit song from 1967.

Like many traditional ballads, “Ode to Billie Joe” uses deceptively simple lyrics to tell its complex story. It begins—as many ballads do—by setting the time and place: “It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day.” The unnamed narrator—female like Gentry, but of an indeterminable age—tells us, “I was out choppin’ cotton, and my brother was balin’ hay.” When everyone sits down for “dinner,” the noonday meal in the Southern vernacular, the mother casually mentions, “I got some news this mornin’ from Choctaw Ridge. Today, Billie Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge.”

The song contains five stanzas of six lines each, slowly building to describe how everyone but the narrator keeps eating the folklore-rich food on the table—black-eyed peas, gravy, biscuits, and apple pie—seemingly oblivious to the tragic news of Billie Joe’s suicide. Choctaw Ridge and Tallahatchie Bridge—the two rhyming place names repeated at the end of each stanza in a ballad-like refrain—have Native American associations, though Tallahatchie also brings to mind the brutal murder of Emmett Till in 1955, because his mutilated body was found in the Tallahatchie River.

According to folksong scholar Lyn Wolz, traditional ballads tell their stories through a series of “vignettes showing different points of the action,” a technique known as “leaping and lingering” that may in the process omit certain details. Gentry may not have been familiar with ballad scholarship, but “Ode to Billie Joe” leaves much to the listener’s imagination in the style of traditional ballads.

For instance, in the penultimate stanza, the narrator hears her mother say, “oh, by the way, [the nice young preacher] said he saw a girl that looked a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge. And she and Billie Joe was throwing somethin’ off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” The final stanza—set one year later—depicts the brother married and living in Tupelo, the father dead from “a virus going ’round,” the mother listless and depressed, and the narrator “pickin’ flowers up on Choctaw Ridge” and dropping them “into the muddy water off the Tallahatchie Bridge.”

What may have been thrown off the bridge remains the song’s biggest mystery and the source of considerable folkloric speculation. Theories abound: it was an engagement ring, Billie Joe’s draft card (at a time when many protesters against the Vietnam War were doing exactly that), a stillborn baby or aborted fetus, or a rag doll—the latter object proposed by a clueless screenwriter in the 1976 film version of the song.

Gentry herself grew very weary of responding to this question. For her, it really didn’t matter. As she told a reporter for Billboard, “Everybody has a different guess about what was thrown off the bridge—flowers, a ring, even a baby. Anyone who hears the song can think what they want, but the real message of the song, if there must be a message, revolves around the nonchalant way the family talks about the suicide. They sit there eating their peas and apple pie and talking, without even realizing that Billie Joe’s girlfriend is sitting at the table, a member of the family.”

Gentry’s insistence on avoiding any sort of resolution to her song has led to one final bit of folklore: what happened to Gentry herself? As the Washington Post reported, “Ode to Billie Joe” sold “tens of millions of copies” and “made Gentry a hot Vegas star,” but then she became “the J.D. Salinger of pop music. She made Harper Lee look chatty. She went full Garbo.” One devoted fan in 2009 even wrote a song, “Where Is Bobbie Gentry?” hoping that it might bring the singer out of seclusion.

The Washington Post reporter used real-estate records to locate Gentry living in “an 8,000-square-foot house with a great pool” presumably near Memphis, which is not too far from Chickasaw County. But folklorists know that most folk prefer to keep alive the mystery—about both Gentry and Billie Joe. Fairy tales may have their happy endings, but ballads and legends typically thrive on unexplained secrets, often dark and deep, like “the muddy water off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” Let’s keep imagining.

James Deutsch is a curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. In August 1967, he drove his Volkswagen bus to Montreal for Expo 67 and heard “Ode to Billie Joe” on the car radio more times than he can remember.