Black History Month gets a special level of attention in Jamaica not merely because of its legendary African heritage, but because February is also Reggae Month. It’s a time for Jamaicans to celebrate their unique contributions to world music. Certainly, they have more than one reason to celebrate.

During the early years of the post-Independence (i.e., 1970s), “roots” reggae music—through its close association with the philosophy and culture of the Rastafari—played a major role in transforming Jamaica’s national identity from one of an Anglophilic British post-colony to a “conscious” Black nation with a proud African heritage. The roots of the Rastafari-reggae nexus traces back to early decades of the twentieth century. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey—the Jamaican-born champion of Pan-Africanism—mobilized millions of Black people in Harlem and across the Diaspora with his vision of racial upliftment and a return to Africa. He encouraged his followers to “Look to Africa where a Black king will be crowned, for the day of deliverance is near.”

In Jamaica, Garvey’s followers remembered this when the young Ethiopian nobleman, Ras Tafari Makonnen, was enthroned in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah. The first Rastafari preachers took the Emperor’s pre-coronation name as their own—pointing to the titles in Scriptures that identified him as the Second Coming (see Revelation 5:5; 19:16)—they proclaimed his divinity. As his rightful subjects, communicants saw themselves as “exiles” in a modern-day Babylon whose redemption required the development of a consciousness that would liberate Black people from the “mental slavery” fostered by enslavement and Eurocentric miseducation about Africa and its peoples.

Decades later, roots reggae music would serve as the medium to carry that message with anthems praising the divinity of the Emperor, recalling the historic struggles of the Jamaican people, and condemning the ongoing inequities and forms of injustice that affect not only Black people, but peoples everywhere. Since the 1970s, reggae—in its varied genres (e.g., roots, lover’s rock, dub, and dancehall), has reached virtually every corner of the globe from Kingston to Cape Town and from Amsterdam to Auckland. At the front of that worldwide trend was Jamaica’s own planetary icon: Bob Marley.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that reggae was recognized by UNESCO and added to the list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2018. What follows is a selective introduction to the origins and development of roots reggae, the music’s original style associated with its most legendary artists and producers.

Jamaican Popular Music and Roots Reggae

Since the late 1960s, reggae has been the primary popular style of music in Jamaica. Its origins reflect the cultural hybridity for which the Caribbean is known. Reggae’s roots trace back to the late 1940s and 1950s when the Jamaican recording industry was in its infancy. Mento—a rural-based music that developed from the period of slavery and which came to be influenced by Trinidadian calypso in the urban context of Kingston, was then the popular music. By the late fifties, a new style known as ska burst onto the urban scene.

As anthropologist Ken Bilby tells it, “Ska was born when urban Jamaican musicians began to play North American rhythm and blues, a style that had penetrated the island via imported records and radio broadcasts from Miami and other parts of the southern United States.”

In addition to the influences of jazz, the rhythmic patterns of Jamaica’s spiritual Afro-Revival music were combined with rhythm and blues to complete the new form known as ska. The tempo of the music was energetic and upbeat, something that most observers take to reflect the Jamaican national mood in the run-up to Independence.

The ska era is of note for several other reasons. It was during this period (1950s to 1966) that sound system dances were in swing in urban Kingston, with many young musicians being influenced by the music that was played. During this period, sound systems—essentially mobile speakers with turntables and amplifiers—became a Black space of national affiliation, significant as one of the only venues in which Jamaican youth began to cross class lines.

Notable ska artists influenced by the sound system phenomena would go on to become reggae artists: notably, the Wailers, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, and Toots and the Maytals. It was also during the ska era that the heartbeat pulse of Rastafari sacred drumming, known as Nyahbinghi, exerted its influence on several ska songs, the most famous being “O’Carolina,” a composition by the Folkes Brothers and the legendary Rastafari drummer Count Ozzie (aka Oswald Williams). For Jamaican listeners, the addition of these Rastafari “riddims” were an explicit way of recognizing and honoring Africa, an element often lacking in American rhythm and blues. Explicit Rastafari themes also began to creep in, notably through the work of the band the Skatalites and their lead trombonist in songs like “Tribute to Marcus Garvey” and “Reincarnation.”

By 1966, as the economic expectations around Independence failed to materialize, the mood of the country shifted—and so did Jamaican popular music. A new but short-lived music, dubbed rocksteady, was ushered in as urban Jamaicans experienced widespread strikes and violence in the ghettoes. The symbolism of the name rocksteady, as some have suggested, appeared to be an aesthetic effort to bring stability and harmony to a shaky social order. The pace of the music slowed with less emphasis on horns and instrumentalists and more on drums, bass, and social commentary. The commentary reflected folk proverbs and biblical imagery associated with Rastafari philosophy, but it also contained references to “rude boys”—militant urban youth armed with “rachet” (knives) and guns, prepared to use violence to confront the injustices of the system.

Needless to say, topical songs, a staple of Caribbean music more generally, were at home in both ska and rocksteady compositions. The ska-rocksteady era was aptly bookended by two songs: the optimistic cry of Derek Morgan’s “Forward March” (1962) that led into Independence and the panicked lament of the Ethiopians’ “Everything Crash” (1968) that spoke to social upheaval and uncertainty of the early post-Independence period.

Roots Reggae Revolution

Reggae music entered the scene in 1968, retaining the basic rhythmic structures of the popular styles that preceded it. This included the syncopated snare drum and hi-hat pulse of ska, the swaying guitar and bass interplay of rocksteady, along with the continuing influence of mento and the Nyahbinghi drumming tradition. Reggae riddims—with their emphasis on the downbeat on two and four—evolved from the signature “one drop” style mastered by Carleton Barrett, drummer for the Bob Marley and the Wailers, to “rockers”—a rhythm most identified with the drumming duo of Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare—to “steppers,” another evolution in the reggae beat.

But it was the topical character of so much reggae that launched a musical revolution. This was reggae’s Rastafari-inspired reckoning with Jamaica’s oppressive past of slavery (think of Peter Tosh’s “400 Years” and Burning Spear’s “Slavery Days”), the ongoing exploitation of the Black masses, and ideology of the elites and middle class who sought to suppress race consciousness as a defining feature of the nation.

Desmond Dekker’s classic early reggae hit in 1968, “Israelites,” was among the songs that heralded the dramatic changes to follow in Jamaican popular music. The song obliquely referenced Black people as the “true” Israelites, enslaved in a modern-day Babylon and longing for deliverance by a righteous God in Zion who would hear their cries. The struggle of the righteous against the oppressive system of “Babylon” was a general Rastafari template for reggae, a music which demanded that the voice of the suffering and oppressed be heard. But it was not the Rastafari themselves who enabled this template. Nor could it be taken for granted that a Rasta-influenced music would prosper given the traditional hostility of the political elites and the middle class to the Rastafari.

Like so many other things that have altered the course of Jamaican history, the birth of reggae music would require a catalyst from beyond the island’s shores. It came in the form of the three-day state visit of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I to Jamaica in April 1966.

Emperor Haile Selassie I—deified by the Rastafari from the early 1930s as their God and King—had attracted the support of the entire Black world when Italy invaded his kingdom in 1935. He arrived in Jamaica not merely as the biblically enthroned monarch of Africa’s oldest state, but as a champion of racial equality and as the recent founding chairman of the Organization of African Unity (1963), the organization then spearheading efforts at decolonization on the continent. Lightning flashed and torrents of rain fell in the hours prior to his landing, but those present swear that the sun broke out immediately as the wheels of his plane touch Jamaican soil.

The Emperor’s plane was greeted by a tumultuous crowd of over 100,000 Black Jamaicans and Rastafari brethren and sistren, many among those who supported him during the Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-41). What followed is now memorialized in oral narratives and song including Peter Tosh’s “Rasta Shook Dem Up” (1966), Early B’s “Haile Selassie” (1966), Don Carlos’s “Just a Passing Glance” (1984), and Capleton’s “That Was the Day” (2004). As the plane taxied into position, thousands poured onto the tarmac, overwhelming the official honor guard and surrounding the Emperor’s plane. The official state welcoming ceremony had to be scrapped as Ras Mortimo Planno, a revered Rastafari leader (and, at the time, Bob Marley’s spiritual advisor), was summoned to quell the crowd and safely disembark the Emperor.

The moment served as a stunning wakeup call for to political leaders who heretofore failed to gauge the scope of the influence the Rastafari had upon the Jamaican masses. Huge crowds assembled at every venue where he appeared and hung on his references to the “shared African blood” and “bonds of brotherhood” between the Ethiopian and Jamaican peoples. In addressing the Jamaican Parliament, he referred to Jamaica as being “part of Africa” and hoped for its prospective inclusion in the OAU.

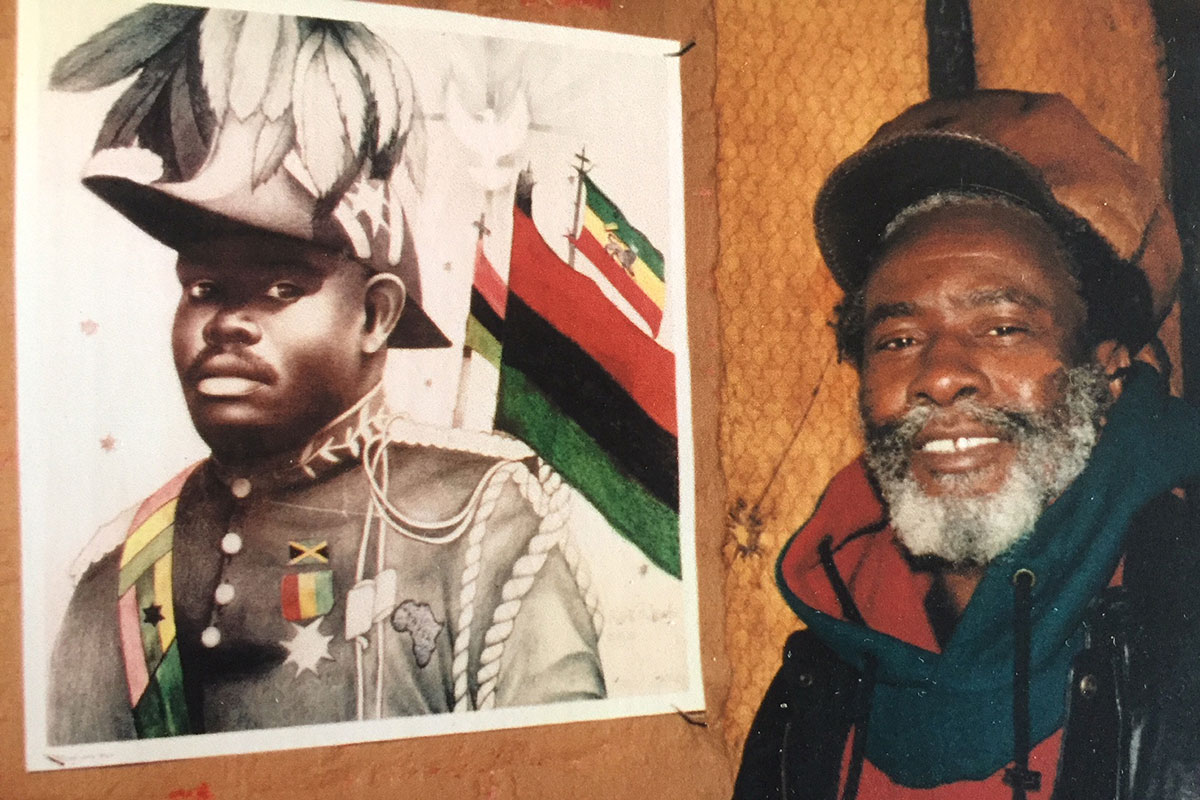

For members of the Rasta movement, the coup de grace was delivered by Haile Selassie himself at the public reception held for him by Jamaica’s governor general. The Rastafari, who had heretofore never taken the national stage, were thrust into the spotlight on that occasion when the Emperor awarded gold medals to thirteen Rastafari leaders for their Pan-African works and commitments. The act had enormous social and political impact. By symbolically repositioning the Rastafari from “outcast cultists” to esteemed bearers of the African heritage, the Emperor conferred legitimacy on the signifying codes (i.e., speech, dress, hair, music) through which the Rastafari have resurrected the concept of African personhood in Jamaica and the world.

In the end, the takeoff of reggae music was defined not only by the Emperor’s attention to the Rastafari, but by the profound impact he had on those who were prepared to see their own Blackness and Africanity in a new and positive light and by the calculations that Jamaica’s political elites would make in response to this. The Rastafari have celebrated April 21, 1966, every year since, naming it “Grounation Day.”

By viewing the roots reggae revolution against the touchstone of Haile Selassie I’s visit to Jamaica, it is easy enough to appreciate the raison d’etre for the long list of songs artists have created—and continue to create—in praise of the Emperor. Notable contributions include Bob Marley’s “ Selassie Is the Chapel,” his first song as a Rastaman in 1968. The song appropriated Elvis Presley’s “Crying at the Chapel” and is an example of the Jamaican penchant for “versioning”—experimenting over the instrumental tracks of music which became popular in the 1960s. Songs that would round out any list in this genre would include “ Satta Massagana” by the Abyssinians, “ Ighziabeher” (“Let Jah Be Praised”) by Peter Tosh, “ Hail H.I.M.” by Burning Spear, “ I Love King Selassie” by Black Uhuru, “ Behold” by Culture, and “ New Name” by Jah Nine.

Reggae and the Spirit of African Resistance

Much has been written about the relationship between reggae and the philosophy and worldview of the Rastafari, but one aspect of this relationship that warrants special note is the sense of time projected in so many original reggae compositions. Musicologist Pamela O’Gorman, who has written extensively on Jamaican music, has observed that reggae songs seem to have “…no beginning, middle and no end. The peremptory upbeat of the traps [drums], which seldom vary from song to song, is less an introduction than the articulation of a flow that never seems to have stopped. This is no climax, there is no end. The music merely fades out into the continuum of which it seems an unending part.”

For those who have listened closely to enough roots reggae, there are clues to what this sense of time represents to a Rastafari “way of being in the world.” Peter Tosh, in his song “Mystic Man,” offers a clue when he sings, “I’m a man of the past, living in the present, stepping in the future.” The line refers to more than the immediate temporal moment as Tosh is speaking about a break with the prevailing Western concept of time and its preoccupation with measurement and regimentation—something that served as the very cornerstone of the plantation system that dehumanized Africans and reduced them to expendable units of Black labor. Perhaps Marley sharpens our understanding of the counter-worldview carried by the drum and bass rhythms of reggae where, in the opening lines to his song “One Drop,” he boldly intones,

Now feel this drumbeat, as it beats within

Beating a rhythm, resisting against the system

We know that Jah won’t let us down

When you’re right, you’re right!

Some have argued that it is the spirit of African resistance found in reggae that constitutes its wider appeal. Sonjah Stanley, director of the Caribbean and Reggae Studies Unit at the University of the West Indies, recently puts it thusly: “Reggae has gone to all parts of the world inspiring people because of the very soul of the music and that soul has to do with an entire history of hardship, of oppression, of rebellion, [and] of enslavement.”

It was from this spirit that the seeds of roots reggae would flower into a golden age (ca. 1968-1983) of music devoted to honoring the history and struggle of Afro-Jamaicans and to “chanting down” the oppressive system of Babylon. Think here of Third World’s memorable anthem “96 Degrees in the Shade” about the Morant Bay Revolt that led to the martyrdom of the Native Baptist Preacher Paul Bogle, now a national hero; Bob Marley’s “War” that put to music part of Emperor Haile Selassie’s 1963 address to the United Nations; “Two Sevens Clash,” “Calling Rastafari,” and “International Herb” by Culture (Joseph Hill); the mind-altering echoic effects and reverbs in “Congo-Ashanti” (1977) by the Heart of the Congos (Cedric Myton and Roy Johnson); “Jah Jah Give Us Life to Live” by the Wailing Souls; and “Garvey” and “Garvey’s Ghost” by Burning Spear (Winston Rodney).

Roots reggae—bearing the unmistakable “vibration” of Rastafari—was not simply a music. It delivered a philosophy that underscored the importance of personal agency in reclaiming one’s history and culture. A number of Marley’s classics—including “Natty Dread,” “Ride Natty Ride,” and the call in “Zimbabwe” that “every man has a right to decide his own destiny!”—emphasize that theme. Perhaps his lyrics in “Rastaman Live Up” best make the point:

Rastaman, live up!

Bongoman, don’t give up!

Congoman, live up, yeah!

Binghi-man don’t give up!

Keep your culture

Don’t be afraid of the vulture!

Grow your dreadlocks

Don’t be afraid of the wolf-pack!

These kinds of songs have inspired more than two generations of not only Jamaicans but Black people in the Atlantic world to think of themselves as “Africans” who consciously stand up for their rights and their culture. Roots reggae not only served as the virtual soundtrack of Michael Manley’s Democratic Socialism during the 1970s, reflecting support for liberation movements on the African continent and the anti-imperialist stance of his administration, it became the most popular music in the Third World. Think of reggae compositions that expressed support for armed liberation movements in the frontline states of southern Africa during the 1970s. Songs like “Apartheid” by Peter Tosh, “War” and “Zimbabwe” by Bob Marley, “M.P.L.A.” (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), “Angola,” and “Che” by the Revolutionaries, “Winnie Mandela” by Carlene Davis, and “Harambe” by Rita Marley.

As Winnie Mandela would attest when she visited Jamaica in the early 1990s, reggae songs like these were routinely listened to in South Africa, Angola, and Mozambique and were a very real source of moral support to African freedom fighters during the years of their liberation struggles. These songs also created a popular concept of racialized belonging shared by both diaspora and continental Africans. Marley’s anthem “Africa Unite” remains perhaps most memorable in this regard, but the calls for social justice and equality in so much reggae strengthens that bond.

While male artists tended to dominate the reggae the roots reggae scene during the 1970s both at home and abroad, as well as during the 1980s when it was popular mostly abroad, female artists have made their contributions. Before joining the I-Threes—the vocal group backing Bob Marley and the Wailers—in 1974, Marcia Griffiths was a successful artist who collaborated with Bob Andy. She had her own solo career and arguably remains the most successful woman in roots reggae. Her 1978 hit “Dreamland” remains a classic. Judy Mowatt, also of the I-Threes, recorded a number of memorable classics on her album Blackwoman (1978), including the title song, “Blackwoman,” “Many Are Called,” and “Sister’s Chant,” the latter evoking the challenges facing the Black woman.

Since the transition of her husband, Bob Marley, Rita Marley continued her recording career and became a Pan-African activist working with governments and groups on the African continent to assist communities. Through her foundation, she mounted the Africa Unite concert series which stive to spread global awareness about and find solutions to issues affecting Africa.

Starting in the mid-1990s, a revival of roots reggae again swept Jamaica, with a host of female artists rising to the fore. To a large extent, this reflects a shift in the formerly patriarchal ideology of Rastafari that began in the early 1980s driven largely by female agency—what Rastafari would term the “Omega Principle,” the necessary balance between man and woman. The genre has seen the emergence of artists like Queen Ifrika (“Lioness on the Rise”), Jah Nine (“New Name”), Hempress Sativa (“Skin Teeth”), Etana (“People Talk”), and Koffee—a young female rapper-DJ who won the GRAMMY in 2019 for Best Reggae Album with Rapture. Certainly there are women in other genres of reggae, most notably in dancehall, but this new generation of artists reflects a promising development with respect to the role of women in roots reggae.

It’s an impressive reach for a tiny island nation. Can you think of a country of comparable size to Jamaica (with approximately 2.5 to 3 million people) that has had a larger impact on the world through popular music and culture? That impact continues to this very day. One need only consider the “Year of Return 2019” campaign mounted by Ghana and its president, Nana Akufo-Addo, to encourage people of African descent in the diaspora to return home. The campaign gave fresh impetus to the vision of Marcus Garvey and the Rastafari of uniting Africans on the continent with their brothers and sisters in the diaspora. While touring in the United States and the Caribbean as part of this campaign, President Akufo-Addo demonstrated his reggae chops by drawing directly from the lines Peter Tosh’s reggae anthem “African”:

Don’t care where you come from

As long as you’re a Black man, you’re an African

No mind your nationality

You have got the identity of an African

On November 26, 2019, at the close of the ceremony in Accra during which over a hundred African Americans and African Caribbean subjects were naturalized as Ghanaian citizens, President Akufo-Addo concluded his speech with Tosh’s lines. His anthem “African” was then played as Ghana’s newest citizens sang and danced in affirmation to its lyrics.

All this just begins to scratch the surface of reggae’s history and reach. As they say in Jamaica, “The half has yet to be told!”

For information on specific artists, bands, and festivals, visit reggaeville.com and reggaefestivalguide.com.

Jake Homiak is a cultural anthropologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. He curated the Discovering Rastafari! exhibition and has dedicated his career to studying Rastafari culture in Jamaica and beyond.

Works Cited

Bilby, Ken. 1985 “The Caribbean as a Musical Region” In Sidney Mintz, ed. Caribbean Contours. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bilby, Ken. 2016. Words of Our Mouth, Meditations of Our Heart: Pioneering Musicians of Ska, Rocksteady, Reggae and Dancehall. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Chang, Kevin O’Brien, and Wayne Chen. 1998. Reggae Routes: The Story of Jamaican Music. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Chude-Sokei, Louis. 1997. “The Sound of Culture: Dread Discourse and the Jamaican Sound Systems.” In Language, Rhythm and Sound: Black Popular Cultures into the Twenty-First Century, edited by Joseph K. Adjaye and Adrienne R. Andrews. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

King, Stephen A. 2002. Reggae, Rastafari, and the Rhetoric of Social Control. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

O’Gorman, Pamela. 1972. “An Approach to the Study of Jamaican Popular Music.” Jamaica Journal 6(7): 50-54.

Stolzoff , Norman. 2000. Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dancehall Culture in Jamaica. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wynter, Sylvia. 1977. “We Know Where We Are From: The Politics of Black Culture from Myal to Marley.” Unpublished paper. The African & Afro-American Studies Program. Stanford University.